How democratic is the UK’s House of Lords, and how could it be reformed?

As part of the 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Sonali Campion, Sean Kippin and the DA team examine how the UK’s deeply controversial current second chamber, the House of Lords, matches up to the criteria for liberal democracies with bi-cameral legislatures. Now an almost-all appointed Chamber, the House of Lords has had some prominent or more bipartisan influence on moderating Commons proposals. But its members remain completely creatures of patronage, and wholly unaccountable to citizens. All parties except the Tories now support its replacement by an elected Senate.

Clerks sit at the Table of the House of Lords. Photo: UK Parliament via a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence

This is an old version of the article. An updated, 2018 edition of this article is now available here. You can also download the full 2018 Democratic Audit from LSE Press here.

What does democracy require for second chambers in legislatures?

- All legislators with a capacity to approve, amend or reject legislation should

- either (and preferably) be directly elected by voters, or

- be elected/appointed indirectly by the elected chamber, or by a government fully accountable to the elected chamber

- In a liberal democracy no legislator should sit in a second chamber (or upper house) simply by virtue of their birth, wealth, or as a result of donating money or services to party politicians.

- Serving in the second chamber may confer distinction, but no part of the legislature should form an integral part of an aristocratic or societal honours system.

- Any appointment of legislators to a second chamber should be vetted by a genuinely independent regulatory body. Mechanisms should be in place to remove legislators who breach legal or ethical standards.

- In any bi-cameral legislature, an upper house should be designed to realise a combination of the following specific constitutional and political advantages:

- Act as a constitutional and policy check on the majority in the elected house, especially by offering a safeguard against legislative changes that breach democratic principles, impair rights or are otherwise ill-advised

- Facilitate the technical operation of legislative drafting, scrutiny and amendment

- Improve the accountability of the executive as a whole to the legislature and to public opinion

- Increase the number or range of access channels from civil society to the executive, in equitable and accountable ways

- Re-balance the geographical representation of different parts of the country – for instance, to secure more equal or greater influence for all component regions/provinces/states within a country

- Improve the social representativeness of legislators

- Widen the range of expertise amongst legislators as a whole

- Provide a mechanism to encourage the continued engagement of ‘emeritus’ politicians in public life

- Offer a measure of policy continuity, especially on issues where civil society actors must make decisions with some long-run predictability.

Recent developments

In 2012, the coalition government introduced the House of Lords Reform Bill to the House of Commons. The Bill would have created a smaller House of Lords in which a large majority of representatives would be chosen in elections by a system of proportional representation, but where a substantial minority of peers would be appointed more or less as now. Additionally, space would be reserved for appointed ‘ministerial members’ and Church of England Bishops. The reforms were essentially wrecked by the opposition of Conservative backbench MPs, combined with the refusal of the Parliamentary Labour Party to facilitate debate (citing opposition to the proposed timetable rather than the substance of the reforms). Some tiny reforms were introduced in 2014 to enable peers’ voluntary retirement, to exclude those given a prison sentence of more than a year, and to allow peers to be excluded if they did not attend the House for an entire session.

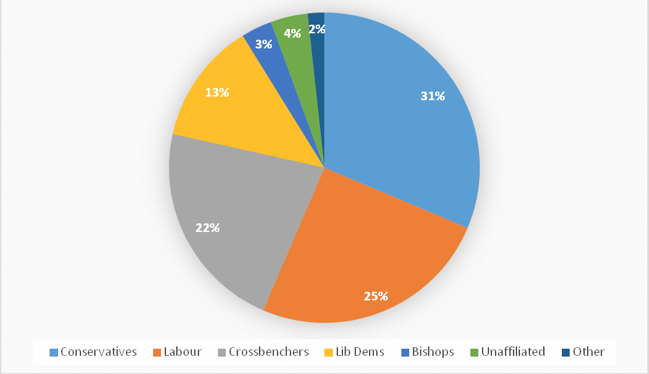

Calls for reform have persisted, particularly since the deputy speaker Lord Sewel was forced to resign, following revelations that he had been filmed taking drugs with prostitutes and commenting in derogatory terms on the Lords’ expenses system. Widespread public and media outrage over a string of misconduct incidents, and unease over the role of party political donations in securing peerages for governing party supporters especially, have been backed up by continued demands for a major reform of the House of Lords. The Liberal Democrats are firm in wanting a democratically elected chamber (but nonetheless have a full quota of members themselves). The Scottish National Party refuses point blank to make any party nominations. Since the SNP now controls every Commons seat in Scotland bar three, has been the largest party in the Scottish Parliament since 2007, and has formed the majority government there since 2011 (and looks likely to continue in power there until at least 2020) – their deliberate and long-term absence makes the Lords even more grossly unrepresentative and south-east England-centric than ever. Chart 1 shows the current party make-up of the House.

Chart 1: Current totals of Lords by party or group

Source: Parliament.uk

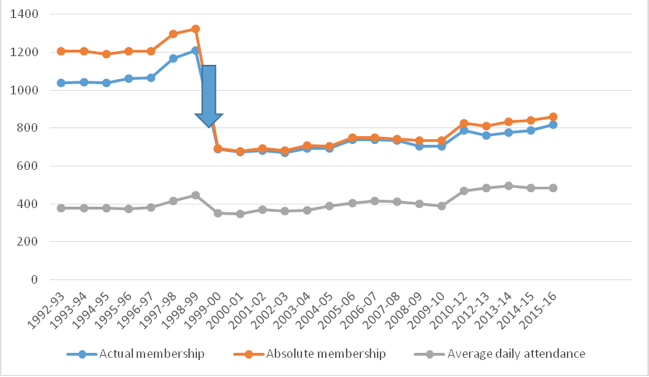

For Prime Ministers and opposition leaders alike, the ability to appoint peers (without any limit) has been politically convenient. David Cameron created new peers faster than any of his predecessors, following a policy that the membership of the House of Lords should be roughly in proportion to the party voting totals at House of Commons elections. Chart 2 shows that the size of the Lords has increased by 27% since 2000, when the blue arrow indicates most hereditary members were removed (if we look at absolute members) and by 21% (if we look at actual eligible members). There is a constant tendency for potential members to decrease, as elderly peers die, offset by bouts of PMs creating new peers for their party (and pro rata-ing for other parties making nominations). (Potential members include those who have retired, or taken leave of absence – it can be seen that in recent years the orange line has again risen above the blue line). The only other countries in the world with second chambers larger than the first are the People’s Republic of China, Kazakhstan and Burkina Faso – none of them liberal democracies.

Chart 2: House of Lords membership and attendance from 1992 to 2015

During the 2010-15 coalition, both Tory and Liberal Democrat peers tended to support their government’s legislative proposals, so that with limited crossbench backing most laws could pass unscathed. However, after the general election the Conservative majority government (with less than a third of peers) has faced both Labour and Liberal Democrat peers in opposition (nearly two-fifths of the House). Since May 2015 ministers have already been defeated 81 times in the Lords, compared to 99 times in the previous five years of coalition. Yet in August 2015 Cameron dismissed the question of Lords reform and reiterated his ad hoc scheme for the numbers of peers to ‘reflect the situation in the House of Commons’, shortly before appointing 40 more peers (of whom 26 were Conservatives) in the Dissolution Honours and a further 16 (13 of them Conservative) in his Resignation Honours. This final list attracted particular criticism for its alleged ‘cronyism’, with a number of key Conservative aides and donors awarded peerages. The only Labour nominee, Shami Chakrabarti, had chaired an inquiry which largely cleared the party of charges of anti-Semitism three months earlier. In total, Cameron appointed 190 peers during his premiership, a faster rate than any PM before him.

The increased Tory representation did not prevent the Lords voting in October 2015 to delay changes to Tax Credits until certain conditions were met. This move sparked outrage from Conservative ministers, who argued that peers were overstepping their constitutional right by meddling with a budgetary matter (albeit intended to be implemented via delegated legislation). Opposition peers countered that the legislation was not a money bill but a statutory instrument, a method seemingly chosen by the government so as to avoid debate and amendment in the Commons, while the cuts themselves were in violation of election pledges given by leading Tories that tax credits would not be changed. Therefore, they argued, it was within their rights to ask the government to rethink.

The former chancellor, George Osborne, subsequently made a virtue out of dropping the tax credit cuts in his Autumn Statement. Nonetheless Cameron set up an inquiry led by the former Tory peers’ leader Lord Strathclyde ‘to conduct a review of statutory instruments and to consider how more certainty and clarity could be brought to their passage through Parliament’ as a result of the dispute. The resulting Strathclyde Review report in December 2015 recommended that the Lords’ (very rarely used) ability to veto statutory instruments should be scrapped, bringing these powers into line with the House’s powers over primary legislation, where peers can only delay action for a year. These contentious recommendations were received with scepticism by the opposition, and were widely criticised for threatening to undermine Parliamentary scrutiny of secondary legislation. Theresa May’s government dropped the recommendations a year later, but with the proviso that they might be revived if peers failed to show “discipline and self-regulation” and continued to veto statutory instruments.

An attempt to end the hereditary peerage elections, in which some or all of the House picks replacements to top up the remaining 92 hereditary peers after one dies, also failed in late 2016 after failing to receive government support.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| In recent years, while observing the ‘Salisbury Convention’ to respect government’s clear general election mandates, the House of Lords has proved willing to defeat ministers, even on flagship and other significant pieces of legislation. This change has led to somewhat greater checks and balances constitutionally and a little more scrutiny in the policy making process, especially on matters not presaged in a winning party’s manifesto. | The House of Lords remains unelected. All peers hold their seats until they die and thus are not accountable to or removable by citizens in any way. |

| Although there have been some questionable appointments of peers over time, a substantial part of the public, many MPs and elites, and the Lords themselves believe that peers bring valuable additional expertise into public life. | The value of patronage power for PMs and party leaders means that the Lords has increased hugely in size (see above). Costs are also substantial - the average peer claims over £25,800 in expenses and allowances per year. One recent investigation also revealed that 15 peers had claimed an average of £11,091 each, despite not speaking in the main chamber during the 2016/17 session. |

| The social diversity of membership in the House of Lords has slightly improved in this century. There are now 209 female (26%) and 51 black or minority ethnic peers (6.4%). | Although outside peerage appointments are scrutinised, party nominations of peers are only lightly and inadequately appraised by a weak regulator (the House of Lords Appointments Commission). Major party donors can still effectively ‘buy’ peerages. |

| Corruption and misbehaviour allegations against peers highlight the openness to abuse that inevitably follows when legislators are accountable to no one and lack any effective oversight. | |

| Ministers in the Lords are not held accountable to the same degree as their counterparts in the Commons. | |

| In all 92 hereditary peers still sit in the Lords, supposedly ‘elected’ but in effect a self-perpetuating oligarchy selecting new members from among the aristocracy with a tiny ‘electorate’. | |

| Uniquely amongst UK religions, 26 Church of England bishops still have seats in the Lords. |

| Future opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| All parties in the centre and on the left of UK politics are now committed to scrapping the Lords in favour of a wholly elected Senate. | The Conservatives remain resistant to any substantial reform of the Lords of any kind, but especially to introduce elections. |

| Systems of election using PR systems, and detailed possible rules and conventions for regulating a Senate’s relations with the Commons and roles in policy-making, have now been worked out. So the traditional stance of Lords’ defenders (pointing to small advantages of existing bi-cameralism as if they would be lost altogether, or suggesting that reform must create new tensions between the chambers) are less and less realistic. | Most existing peers will undoubtedly seek to wreck any serious reform of the chamber, resisting to the last ditch (witness the survival of the oligarchy of 92 hereditaries). |

| After the 2014 Scottish referendum, and the ad hoc EVEL (English votes for English laws) changes of 2015, the urgent need to reach a proper devolution settlement for all parts of the UK opens up a potentially key new constitutional role for an elected Senate. Greater devolution of Whitehall powers to English city-regions may also help in this area. | It seems likely that any substantial reform will need to be put to a referendum, at which only a coherent and low-cost scheme could succeed – and for which there is not yet consensus agreement between the parties or in public opinion. |

| Lord Grocott has made persistent efforts to abolish the hereditary by-elections system, introducing a private member's bill in the 2015-16 session (which was blocked at committee stage) and again in 2017-19 (which is awaiting its committee stage). |

Ministers in the House of Lords

At present around one in five ministers, 20 in all, sit in the Lords and are accountable only to other peers, providing no direct link between them and voters to create legitimacy and accountability. Admittedly, no Secretaries of State currently sit in the House of Lords. But the only form of scrutiny of peer ministers by MPs is currently through the Commons committees, which very infrequently ask them to give evidence. A possible reform would be to allow ministers from the Lords to answer MPs’ questions in the House of Commons or in Westminster Hall.

Independence of the House of Lords

The chamber continues to act with a reasonable degree of independence from the government, as shown by the tax credits defeat in autumn 2015, the difficult ride given to the controversial Health and Social Care Bill in 2012 (in contrast to its easy passage through the House of Commons) and the rebellion over the right of EU citizens to stay in the UK after Brexit. The mauling of ministers’ proposal by peers in this case contributed to a government’s ‘pause’ and re-consultation, following which the NHS ‘reform’ legislation was somewhat redesigned. These changes to more even-handed scrutiny have come as something of a shock the Conservatives, who always dominated the Lords under the hereditary system and when in power were therefore used to suffering far fewer defeats than Labour governments did. Furthermore, Lords defeats since 2010 have frequently been on significant pieces of legislation including some relating to immigration, pensions, anti-lobbying, financial services, children and families, welfare reform and legal aid. In many of these cases the amendments passed by the Lords were accepted by the Commons, often bringing about better policymaking. The pattern of defeats and amendments suggest that the Lords continues to play a significant legislative role on issues where the heavily whipped MPs in the Commons at times seem incapable or unwilling to act.

Issues around membership of the House of Lords

Analysis by the SNP showed that nearly three quarters of 62 peers appointed in the second half of 2015 were former MPs, special advisers or party aides. Only four academics and two NGO or third-sector figures entered the Lords in this time, suggesting that little diversity of expertise is being brought into play by the current House. Just over a quarter of eligible peers are women and only 6.4% is black or minority ethnic. The only other parliamentary chambers in the world to still include hereditary members of the aristocracy are in the tiny polities of Tonga and the Kingdom of Lesotho. Territorial representation is particularly poor, with limited representation of those outside the South East of England. After a flurry of appointments during the 2000s, the House of Lords Appointments Commission – which has only appointed crossbenchers – has been told to recommend only two new appointments each year; in 2016 there were none. The only other parliamentary chamber in the world to include representatives from the state religion is the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Expenses abuse in the House of Lords

The House of Lords periodically hits the headlines due to expenses scandals which highlight the on-going openness of the Upper House to financial misuse. In 2014 Lord Hanningfield was suspended for a year after being convicted of abusing expenses for a second time (he served time in prison for his first offence in 2011). Worryingly, Hanningfield offered to reveal another 50 Peers who were also claiming allowances for days when they undertook no work in the Lords, although he did not actually name anyone when pressed. He also claimed: ‘I was unaware that what I was doing was wrong’. In 2015, alongside the allegations that Lord Sewel had spent public money on drugs and sex workers, the Lord Speaker, Baroness D’Souza, also came under fire for her ‘downright frivolous‘ attitude to public money. An FOI request revealed she had fuelled substantial ‘unnecessary’ spending on ministerial cars and international travel. With ministers confirming plans to reduce MPs from 650 to 600 as part of the boundary review in order to “cut the cost of politics’, the uncontrolled growth of the Lords seems even more problematic. Indeed, the Speaker Lord Fowler has said it is hard to justify.

Proposals for reform

In its 2017 manifesto, Labour called for a democratically-elected second chamber and, in the interim, the removal of the last hereditary peers (mostly Tories) and a ‘wider package of constitutional reform’ that would reduce the size of the House.

The Liberal Democrats previously reiterated a commitment to reform based on proposals in the failed 2012 Bill, while the SNP and Greens supported scrapping the Lords in favour of a fully elected chamber. All these stances seem to recognise the past attempts at ‘tweaking the Lords’ have not addressed the chamber’s systemic problems, and that only a fresh, elected Senate can really bring about the changes that are needed.

However, in their 2015 manifesto the Conservatives recognised only the case for ‘introducing an elected element’, but emphasised this would not be a priority. Cameron flatly refused to discuss reform on the scale demanded by the opposition parties. Some commentators, including Lord Tebbit and Meg Russell. have even suggested Cameron might have deliberately undermined the Lords through his uncontrolled appointments.

By 2020 more than a quarter (211) of peers will be over 80, and Lord Steel has suggested introducing a retirement age. However, Russell has pointed out that this measure if adopted alone would lead to an uneven party balance, and would not prevent prime ministers from appointing large numbers of new peers to replace them. Even simply imposing a cap on numbers would reduce the proportion of crossbenchers, since PMs tend to appoint overwhelmingly from their own party.

Conclusion

New Labour’s compromise changes to keep only a self-perpetuating oligarchy of hereditary peers in the House of Lords and to move it to being an overwhelmingly appointed-for-life body appear to have perhaps increased its role and significance. However, the case for reform is also now impossible to ignore. The growth in membership and costs is unsustainable, its territorial representation is lamentable, the UK’s fourth-largest party is boycotting it, and the current members lack all democratic accountability and legitimacy. The Lords are sustained only by Conservative party support, its convenience as a source of Prime Ministerial patronage and the still-significant barriers to meaningful reform. If current government quiescence and the self-interested opposition of peers themselves are to be overcome, opposition parties favouring major reform need to crystallise (and coordinate) their proposals for replacing the Lords with an elected Senate, potentially through a Constitutional Convention.

This post does not represent the views of the London School of Economics or the LSE Public Policy Group. Additional research and graphics were provided by Richard Reid of the University of Canberra, DA editor Ros Taylor and the co-Director of Democratic Audit UK, Patrick Dunleavy.

Sonali Campion is a former editor of Democratic Audit UK and the current editor of the LSE’s South Asia blog.

Sean Kippin is a former editor of Democratic Audit UK.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

How democratic is the UK’s House of Lords, and how could it be reformed? https://t.co/5eQnibU6TQ

[…] The team at Democratic Audit have put together a great analysis of the House of Lords and its democratic credentials (and lack thereof): https://www.democraticaudit.com/?p=19837 […]

How democratic is the UK’s House of Lords and how could it be reformed? https://t.co/39lHVwT0Za

How democratic is the UK’s House of Lords, and how could it be reformed? https://t.co/U4n9mZDCK9

How democratic is the UK’s House of Lords, and how could it be reformed? https://t.co/w4PcFvriKp

How democratic is the UK’s House of Lords, and how could it be reformed? https://t.co/qLcTo6bxHi

How democratic is the UK’s House of Lords, and how could it be reformed? https://t.co/iySneLcCOW

How democratic is the UK’s House of Lords, and how could it be reformed? https://t.co/Wl59ZAj2Vf https://t.co/uvDVga5EOw