Still united in diversity? The longer a country is part of the EU, the stronger its citizens support liberal democratic values

What effect does EU membership have on the values of citizens? Drawing on recent research, Odelia Oshri, Tamir Sheafer and Shaul Shenhav assess the extent to which the EU has been successful in instilling the democratic values in its own citizens that it claims to promote externally. The research demonstrates a strong connection between a state’s duration of EU membership and the degree to which its citizens adhere to liberal democratic values, suggesting that while multiple national identities exist across the EU, it is nevertheless possible to unite citizens under the umbrella of democratic ideology.

Can the EU socialise its member populations into the liberal democratic values it purports to espouse? Rather than seeking to detect the rise of specifically ‘European’ values and identifications, as done in much of the preceding research, in a recent paper my co-authors and I decided to focus on popular adherence to general liberal democratic values. We found that membership duration in the EU is associated with citizens’ adherence to EU liberal democratic values. As such, our findings show that the longer a country has been a member of the European Union, the stronger its citizens support the EU values.

Recalling the legitimacy and community deficits from which the EU suffers, the calls to restrict further integration and the proliferation of Eurosceptic sentiments, these findings come as a surprise. Nevertheless, theories on socialisation (and specifically the so called ‘Social Identity Theory’) predict the socialisation effect of the EU on its rank-and-file citizens. Why? Since they have been more profoundly socialised into EU democratic norms, residents of older member states are likely to express more support for democratic values than those of newer member states or non-EU members.

According to Social Identity Theory, groups usually form a core of values shared by their members. To gain positive self-esteem, individuals develop stereotypes based on group affiliations, and these perceptions of group membership can, in turn, lead to the acceptance of group norms. We hypothesised first that citizens of old member states will support democratic values to a greater extent than citizens of new member states or non-EU members. Second, we postulated that this support grows as a country accumulates more years of membership in the EU. These theory-laden assumptions are corroborated by the explicit efforts on the part of the EU to foster democratic values by enhancing democratic policies, enacting human rights laws and promoting democratic policies vis-a-vis accession countries.

Drawing on public opinion surveys and employing multilevel models, we isolated four different democratic values: general/specific support for democracy, minorities’ rights, and anti-authoritarian attitudes. Our models demonstrate evidence in favour of the socialisation hypothesis, according to which membership of the EU fosters adherence to EU democratic values among citizens of the member states.

Our analyses revealed a significant effect of membership time on the support for democratic values. This effect endures even when other factors are taken into account such as a country’s GDP per capita and democratic institutions, respondents’ education or income. This effect has also been shown to persist when a comparison is drawn cross-nationally, that is, between old members and new or non-members, as well as longitudinally, within countries over time.

Put simply, we found that on the aggregate and individual levels old EU member states identify more with democracy than new EU member states or non-EU member states. Specifically, we found that mean support for democracy in a country with 57 years of EU membership is expected to be 12 percentage points higher than for a country with only 4 years of membership, and 14 percentages higher than for a non-member country.

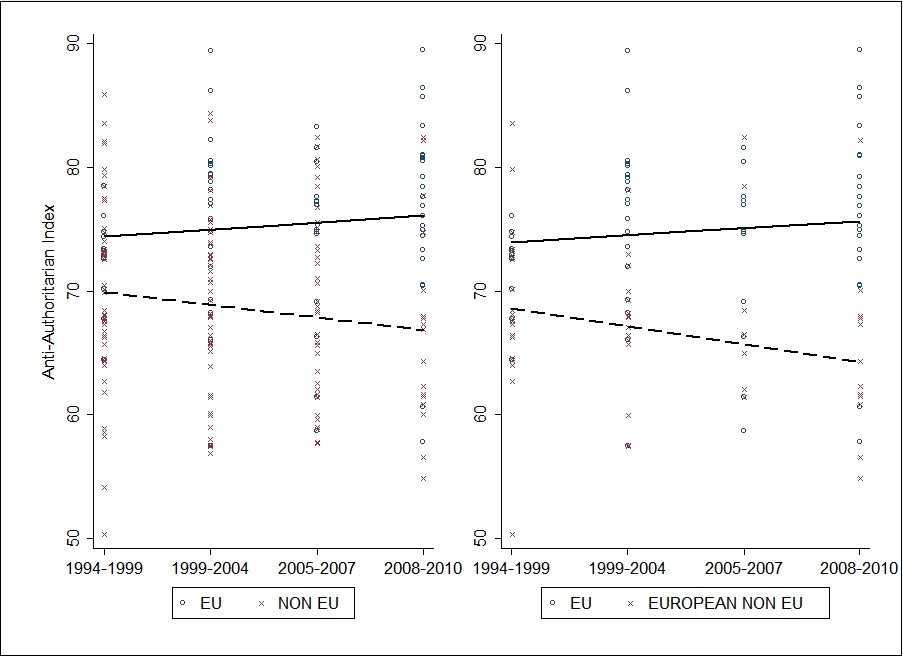

The graph below displays differences in mean support for anti-authoritarianism for the group of EU members and for different groups of countries that are not EU members. It shows that EU members demonstrate higher support for anti-authoritarianism than non-members and that the change over time for member states trends slightly upwards, whereas for non-members – downwards.

Figure 1. Changes in mean support for anti-authoritarianism for countries grouped into EU members (solid line) and non-EU members (dotted line). The left-hand panel (N=219) compares trend in support for anti-authoritarian attitudes between European members and non-member countries while the right-hand panel (N=130) displays trend in anti-authoritarian attitudes for EU members vis-à-vis European non-EU members.

A hurdle for this research project was addressing the cause-and-effect problem according to which only countries that meet basic liberal democratic criteria are allowed to join the EU in the first place. So citizens of EU member states might support democracy to a greater extent than non EU citizens, regardless of their EU membership. To address this issue of endogeneity we used three strategies.

First, we compared the average change over time in the support for democratic values among the group of EU members to such change among different groups of non-EU countries, including a group of wealthy developed European democracies (especially Switzerland, Norway and Iceland) which are not part of the EU. Second, the analyses include a linear time effect to preclude the possibility of finding a longitudinal correlation due to common trending alone. This trending might be that globalisation per se and not membership of the EU, is the cause for growing support for democracy. Finally, the alternative hypothesis that support for democracy is normally the highest in consolidated democracies is eliminated by controlling for the countries’ democracy level.

We decided to use democratic values as a proxy for European identity mainly because the EU has not declared on any occasion that it seeks to promote a unique European identity; in fact, quite the opposite. The EU’s motto is united in diversity, meaning that the many different cultures, traditions and languages in Europe are considered to be an asset that the EU intends to preserve. Instead, we know that the EU fosters democratic values.

We may be witnessing a highly sophisticated approach in this sense on the part of the EU, which is attempting to set democratic norms concomitantly with building supra-national institutions. Rather than becoming a battlefield rife with struggle among conflicting and often incompatible collective identities, the EU seeks to unite its citizens under the normative umbrella of democratic ideology.

This strategy allows Europeans to retain their identities while setting up the normative rules which enable these multiple identities to co-exist. Promoting legalistic values, such as anti-authoritarianism, weakens conflicting particularistic identities, on the one hand, while strengthening citizens’ willingness to accept EU institutions, on the other. The findings of our project show that such a value-based identity is in the making.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. It originally appeared on the LSE EUROPP blog. For more information about the research, see the authors recent paper in European Union Politics.Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Odelia Oshri – Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Odelia Oshri – Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Odelia Oshri is a PhD candidate in the Political Science Department, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Her research is concerned with socialization and identity building in the European Union.

Tamir Sheafer – Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Tamir Sheafer – Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Tamir Sheafer is a Professor in the Departments of Political Science and Communication and Vice Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He has published numerous articles in international peer-reviewed journals in political science, communication science, and public opinion. He is the Associated Editor of Political Communication, and on the editorial board of Public Opinion Quarterly and the International Journal of Press/Politics.

Shaul Shenhav– Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Shaul Shenhav– Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Shaul Shenhav is an associate professor at the Department of Political Science, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His research interests include political narratives, political discourse, rhetoric, public diplomacy, and Israeli politics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Still united in diversity? The longer a country is part of the EU, the stronger citizens support democratic values https://t.co/eTJp4aBGuu

Still united in diversity? The longer a country is part of the EU, the stronger citizens support democratic values https://t.co/YV5axZaNkE

The longer a country is part of the EU, the stronger its citizens support liberal democratic values https://t.co/TDgN1eZxn6

Research: The longer a country is part of the EU, the stronger its citizens support liberal democratic values https://t.co/IlZHFjURAv

The longer a country is part of the EU, the stronger its citizens support liberal democratic values https://t.co/oHVbMD7qeQ

Still united in diversity? The longer a country is In EU, the more its citizens support liberal democratic values https://t.co/Z9TGEKaqFu

Still united in diversity? The longer a country is part of the EU, the stronger its… https://t.co/AQkmOXzjBE https://t.co/pLQUFHwhzQ