The Budget will give clues as to how far English devolution marks a radical change for local government

For all the focus on Europe, it could be devolution that is the critical constitutional change of our era. Ahead of tomorrow’s Budget announcement, Andrew Walker looks in depth at the prospects for radical change in local government.

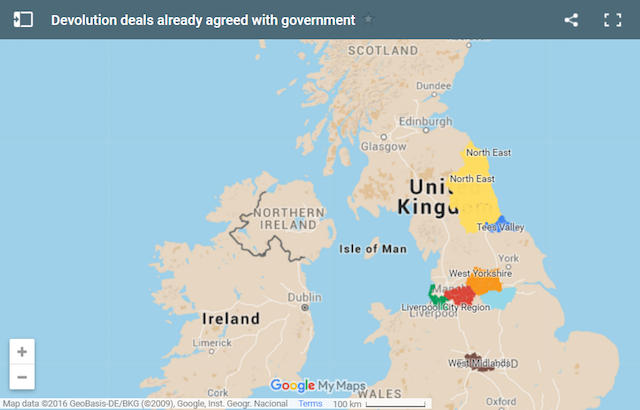

Image source: LGiU long read ‘Devolution: A state of the nation assessment‘

The Budget on Wednesday will give a strong indication of how the government’s devolution programme will play out, whether it will it lead to meaningful change in centre-local relations, or whether it will be another instance of central government using councils as a tool to implement their wider programme.

Success will depend on a few crucial factors:

- How well it actually delivers on its promise to increase economic growth, which, many critics have warned, is not a given.

- Where the goal posts end up. In practice devolution is a process, not a single event. The Cities and Local Government Devolution Act provides a framework but we are yet to see what will actually be made of it and how future deals will be made.

- Rural areas. The driving force behind devolution was always growth in cities, so what happens in (largely Tory) county deals will be important.

National governments’ policy goals often play out in the arena of local government. Historically, the changes that are imposed on councils are the product of the wider political programmes that parties adopt when they come in to power.

The current plan is to use councils as a mechanism to drive balanced economic growth. They will be made financially independent by 2020, with the power to keep and vary business rates, as well as other local taxes, as an incentive to encourage businesses and economic activity.

Local government has borne the brunt of financial reform so far. There is a yawning gap between the resources required to run services and those available. Meanwhile there is the long-standing imbalance between prosperous and less-prosperous parts of the country, particularly between the South East and the North.

Governments have been seeking geographical “enabling frameworks” in order to promote development throughout England. City-regions are the most recent iteration and the government leapt on them as a model for reforming and innovating at scale. Perhaps their greatest champion of cities is Lord Heseltine, whose 2012 paper No Stone Left Unturned: In pursuit of local growth made the case for streamlined city governance and greater local control over economic development.

It soon became apparent that this would be the focus for a Conservative government and the first wave of city-deals came in 2012, followed by a second wave in 2013-14.

Since Heseltine’s paper the government deployed an interesting deal-based, almost Burkean, style of policy making. Rather than rushing to put together a national framework for devolution, government opened up the bidding, allowing councils to submit proposals for how their area might use devolved powers.

The first deal was struck with the Greater Manchester Combined Authority in November 2014, followed by deals with Sheffield and West Yorkshire before the 2015 election, and Cornwall, the North East, Tees Valley, West Midlands and Liverpool City Region after the election.

Yet the government knows what it likes and it knows what it doesn’t. As the negotiation process has extended beyond cities to counties and non-metropolitan areas there are some very clear ideas in Westminster about what these deals should entail. They must be business oriented, for example, with a prominent role for Local Enterprise Partnerships, and there is an enthusiasm for mayors, which seems to be getting stronger with time.

And now the Cities and Local Government Devolution Act has established a legal framework for devolution. Amendments, written in to the Act late in its passage through Parliament, give wide scope for the Secretary of State to make governance changes to local authorities, including to the constitution and members, as well as the structure, electoral and boundary arrangements.

There are concerns with the process as well.

As the policy has been driven by individual deals, there is an inherent level of secrecy involved, which has troubled some. Engagement, accountability and scrutiny have all been raised as significant issues. Others worry about an under-the-radar local government restructure, as well as the lack of clarity about what is actually on offer, the divide and rule tactics and the rapid pace of change. The Mayoral model has also been a serious sticking point, particularly in county areas.

However there was also praise for the fact that the government has got the ball rolling. Pragmatic negotiators recognise that current deals could be a stepping-stone to further devolution in the future.

Meanwhile, the process is exacerbating a number of significant cleavages across the political landscape. These are apparent between central and local government, between different tiers of local government, and within the main parties.

A further worry is that mayors and local MPs may find themselves in conflict, with overlapping remits. There are already reports of MPs making their presence felt in negotiations, which have not helped to ease tensions.

So where does that leave us?

There may be big unintended consequences, as often happens when one arm of the state is used as a tool to ram home the policy goals of another. How much consideration has really been given to the disparities that might be exacerbated between successful and unsuccessful areas, let alone the prospect of some places falling by the wayside entirely. Is there a long-term plan to allow some parts of the country to “fail”, as with the likes of Detroit in the USA, when the RSG is removed in 2020?

Neither the process, nor the Act, has dealt adequately with issues such as democracy, representation, and civic identity. The deal process in particular has been closed to the wishes of local citizens, and even council leaders have been the weaker party in negotiations. County Durham is the only authority so far to consult the public on their proposal. Citizens had the chance to approve the bid in a poll carried out in February. On the whole it has been subject to ministerial will, perhaps even to the will of other unelected figures close to the government.

At some point in the near future it is likely that we will reach a tipping point whereby the deal-based approach falls away and devolution becomes de facto national policy, with a framework drawn up and put in place across the country.

There will be a further challenge in clearly defining where power and responsibility lie. Mayors will be accountable upwards to the government and downwards to citizens and stakeholders. The new elected mayor in Greater Manchester, for example, will report to the scrutiny committee of the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, drawn from the “Scrutiny Pool” of 30 councillors from the ten authorities.

Despite these arrangements we may start to see that soft power is more decisive than some have considered. Informal brokerage, leadership and negotiation could be key to combining health and social care, for example, though the mayor will have no formal responsibility in that area.

As with previous governments, local government is the arena in which a broader political programme is to be enacted. Whether in practice this is a radical change for the better or just tinkering around the edges we will begin to find out soon. It is certainly incumbent on councils to grasp the nettle by facing up to the offer pragmatically and positively.

To paraphrase Anthony King and Ivor Crewe in The Blunders of Our Governments, we have decided what is to be done, now local government will begin the doing of it.

—

This article is a summary of an LGiU long read ‘Devolution: A state of the nation assessment’. The full piece can be accessed here. The post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit UK. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Andrew Walker is a researcher at LGiU and a PhD candidate Queen Mary, University of London, with the Mile End Institute.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

The Budget will give clues as to how far English devolution marks a radical change for local government https://t.co/rYYmPh2DcM

The Budget will give clues as to how far English devolution marks a radical change for local government https://t.co/F6JRfip9rM

@democraticaudit It won’t because there is NO proposal for English Devolution; viz Scotland. at all merely a little bit of Decentralisation

The Budget will give clues as to how far English devolution marks a radical change for local government: https://t.co/NzfdMSj2oo

My piece on devolution for @democraticaudit https://t.co/Ei1eLsw86x

The Budget will give clues as to how far English devolution marks a radical change for local government https://t.co/J7GBOKr7cM

The Budget will give clues as to how far English #devolution marks a radical change for local government: https://t.co/YNGx7aPtOG #localgov

The Budget will give clues as to how far English devolution marks a radical change for… https://t.co/xiaatZk4uP https://t.co/0rstPSsWHt

@democraticaudit That’s silly as NO English Devolution is being implemented on a par with Scottish National Devolution! #WeeDecentralisation

@democraticaudit that’s not devolution that’s the divide & rule. When will the English people have say? https://t.co/oiUilFw3TJ