The Independent Commission on Freedom of Information shows that there is no going back to the “dark ages” of government opacity

Freedom of Information, since its inception by the previous Labour government, has proven popular with the public and press, but troublesome for the politicians who have to navigate a new and transparent world. Here, Tom Felle, welcomes the findings of the the Independent Commission on Freedom of Information, arguing that its conclusions clearly support the continuation of the law and the notion that there is no going back.

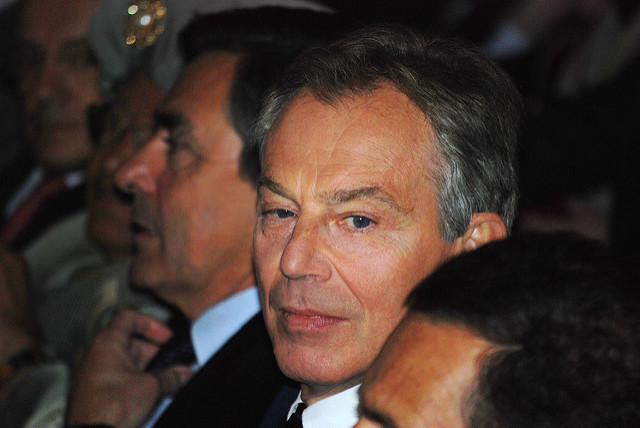

Tony’s “worst mistake”Credit: Andrew Newton, CC BY SA 2.0

The publication of the report of the Independent Commission on Freedom of Information is a welcome protection of the value of openness and transparency at the heart of government.

There were many commentators who worried that the Commission would recommend wholescale changed that might allow the Government to fillet the Act. Indeed commentators, including myself, had predicted draconian changes that may have included greater secrecy provisions, and the introduction of fees for requests.

In the end the report was a welcome relief, and while it made some recommendations for legislative changes to strengthen secrecy provisions in specific areas, the broad thrust of the 58-page document vindicates the UK’s openness and transparency regime and even offers some proposals for areas where it might be strengthened. The Government has ruled out any legislative change.

Freedom of Information legislation celebrated 10 years in existence in the UK last year, but it has never been universally loved. The legislation, which grants a right of access to documents held by public bodies save for certain explicit exemptions, is designed to increase transparency and openness in public bodies, offers greater accountability, and at a stretch might offer greater public understanding of the decision making processes of government and public institutions.

For a country that championed the Official Secrets Act for more than 100 years, the cultural change that it has brought about in just 10 years has been extraordinary. The legislation has uncovered law breaking and corruption in parliament; it has transformed the relationship between citizen and the state; and it has greatly improved accountability measures and has led to never-before seen transparency and accountability in public bureaucracy – restaurant hygiene ratings, hospital inspection reports and police crime statistics, once an ‘official secret’ are now available openly.

Despite this, some civil servants, government ministers and local councils have never warmed to the legislation. Mandarins claimed that they need “safe space” to offer frank advice to ministers while ministers have claimed that the collective decision making processes of government need to be protected.

FOI critics have powerful friends, and have included Tony Blair (who wrote in his memoirs that it was his worst mistake in office) and the Prime Minister David Cameron, who complained that FOI “furs up” the work of government.

To some extent these claims do have merit: For news organisations, particularly tabloids, that boil everything down to black and white issues, while there have been major exposes of corruption and wrongdoing as a result of FOI, documents released as a result of the legislation have far too frequently been used to paint frank advise from officials as ‘dire warnings’ that were ignored, and audits that rightly uncovered minor mistakes, as massive frauds, bungling incompetence or cover-ups.

At a local level, FOI is sometimes used by the media as a substitute to real reporting, with some local media organisations filing copious requests each week. Local government managers say their staff spend so much time administering FOI requests in some cases that it is impacting negatively on productivity elsewhere.

Therein lies the eternal tension. Freedom of information, defended by open government campaigners, journalists and NGOs, laud it as a sunshine law, shining light on the dark recesses of closed government, levelling the playing field between citizen and the state.

Those opposed argue it does more harm than good, damaging the decision making processes of government, denting the ability of officials to offer frank advice to ministers, and reducing all decisions to newspaper exclusives about internal doomsday warnings that were ignored, or rows about spending on toilet paper and chocolate biscuit expenses.

It is, in essence, intensely political.

All of these grievances, and more were aired during written as well as oral evidence to the Independent Commission. It received more than 30,000 submissions and held oral hearings in January this year. It was charged with answering six key questions via its terms of reference, namely:

- Was there a need to strengthen the powers of public bodies to refuse access to sensitive records to ensure internal deliberations were protected from disclosure

- What protection should there be for information relating to collective Cabinet discussion and disclosure

- What protection should there be for risk assessments

- Did the executive veto need strengthening

- What is the appropriate enforcement and appeals system for FOI requests?

- Is the burden imposed on public bodies as a result of having to deal with FOI justified by the public’s right to know.

Members of the Commission included former Labour Foreign Secretary Jack Straw, the former Ofcom Chair Dame Patricia Hodgson, former Liberal Democrat MP Alex Carlile, former Conservative Party leader Michael Howard. It was chaired by the former Permanent Secretary to the Treasury Lord Terry Burns.

The Commission’s recommendations did include recommendations to introduce a more robust provision in the Act to protect internal communications that relate to government policy, and similar provisions to protect collective cabinet decision making, and risk assessments in specific circumstances– though not wholescale changes that would have been tantamount to blanket secrecy provisions being reintroduced.

It also recommended changes to the public interest test to make it more difficult to argue a public interest in favour of release in these areas; changes to the appeals mechanism, and recommended that the Government legislate to give itself a veto over the release of information under the Act – which had been overturned by the Supreme Court in the Prince Charles Black Spider Memos case.

What was most notable, however, was the tone of the Commission. In many cases it acknowledged that even in areas where it was making recommendations increase secrecy provisions in the law, a balance needed to be struck to protect the public’s right to know.

In terms of strengthening the Act, it recommended the introduction of a time limit on the extension a public body can claim, and on internal appeals, so that requests are answered more expeditiously; and it recommended strengthening the Information Commissioner’s powers to act as a guardian of the legislation, to monitor compliance, and punish public bodies who do not comply with the Act.

The Commission acknowledged that many of the submissions it received were overwhelmingly in favour of FOI, and included proposals to strengthen the Act, which as extending its scope to include private companies that provide public services, though it said it could not make any recommendation on this issue.

The Information Commissioner, Chris Graham, during oral evidence to the Commission earlier this year, said that any changes to the Act that increased secrecy provisions, or tipped the balance away from the public’s right to know, would be akin to a “return to the Dark Ages”.

The public, perhaps most vocally expressed through the media and civil society groups, demanded that level of openness and transparency from public bodies, and the Independent Commission has given considerable backing to that proposition.

Despite the hopes of some in Whitehall and elsewhere, there can now be to going back to the Dark Ages.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit, the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Tom Felle is a lecturer at the Department of Journalism, City University London. He can be emailed here.

Tom Felle is a lecturer at the Department of Journalism, City University London. He can be emailed here.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] Note: this post represents was originally posted on Democratic Audit. […]

[…] Note: this post represents was originally posted on Democratic Audit. […]

The Independent Commission on Freedom of Information shows that there is no going back to the “dark ages” https://t.co/by68752bWg

The Independent Commission on FOI shows that there is no going back to the “dark ages” of government opacity https://t.co/7jLJ0LTx3w

[…] Democratic Audit keeps up the conversation on FoI and open government: https://www.democraticaudit.com/?p=20481 […]

FOI Commission report shows there’s no going back to the ‘dark ages’ – my analysis on the @democraticaudit blog https://t.co/eNlQ9ZlN3R

There is no going back to the “dark ages” of government opacity,says T Felle: https://t.co/RKjUfAa73u

@democraticaudit

Independent Commission on #FOI shows that there is no going back to “dark ages” of government opacity https://t.co/UfywF9BVCt | @tomfelle

The Independent Commission on Freedom of Information shows that there is no going back to… https://t.co/1dRRYKcc7K https://t.co/R6e9hM3CzN