England’s 2016 local elections: an indicator of the national political picture?

England goes to the polls on 5 May to vote in a variety of elections. Tony Travers and Martin Rogers highlight a number of key contests to analyse how local elections can affect local services, and also help to reveal the national political picture.

An indicator of the national political picture

On Thursday 5 May 2016 England will go to the polls to elect members of the London Assembly, English Local Government and Police and Crime Commissioners as well as four Mayors, including London’s Mayoral contest. These elections are important both in terms of who runs local government and services at the local level and for the national political picture. Local elections have in the past been a significant pointer to who will form the government after the next election.

Local government elections take place every year, though there are different patterns of election from place to place. In some councils, for example counties and London boroughs, all councillors are elected every four years. In others, including some unitaries and shire districts, half of the councillors face election every two years. A third pattern, involving metropolitan districts, some unitaries and some shire districts, sees a third of councillors elected every year for three years, with no poll in the fourth year.

Consequently, not all councillors are up for election every year. In some years, local elections are in predominantly urban areas, while in others it is mostly rural councils which vote. May 2016 will see elections in metropolitan districts, some unitaries and some shire districts within England. There are no local elections (apart from by-elections) in Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland this year. There are also mayoral elections (in addition to London) in Bristol, Liverpool and Salford.

These elections are important both in terms of who runs local government and services at the local level but also because they provide an indication of the national political picture. Local elections are a significant indicator of who will form the government after the next General Election as they tend to give a clear picture of the state of national politics and are based on actual votes cast rather than polls. For example, the 2011 local elections foreshadowed the SNP’s 2015 General Election Landslide.

The unexpected triumph of the Conservatives at the 2015 General Election led Labour and the Liberal Democrats to elect new leaders. Jeremy Corbyn and Tim Farron need strong local election results to show that their parties are recovering from a poor performance last year.

The ‘national equivalent vote share’ calculations (adjusting the vote share for each party in a particular year’s set of elections so as to reflect the result if there had been an election in all parts of the country) made by academic experts will make it possible to see if Labour and the Liberal Democrats have improved on their 2015 vote share. David Cameron and the Conservatives also need a positive result to steady the party’s nerves following the resignation of Iain Duncan Smith.

National equivalent vote share and General Elections

Excluding General Election years, the government has outperformed the opposition in local elections on only six occasions since 1979: 1982, 1984, 1988, 1998, 1999 and 2011. In every one of those the Government secured re-election at the next General Election. Therefore these local elections are important as they give an indicator of the state of the parties and are also likely to reflect the government after the next General Election.

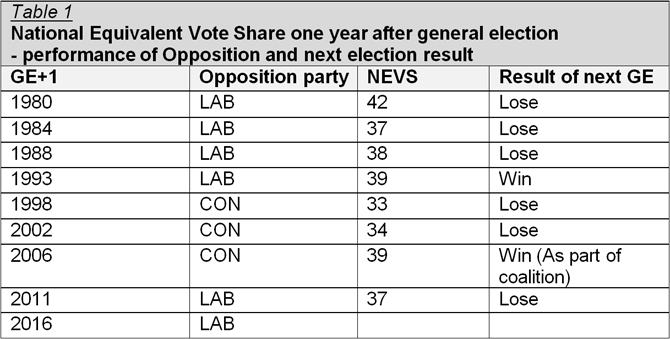

The tables below consider the performance of the major political parties in local elections in the period since 1979. Using ‘national equivalent vote share’ (NEVS) figures, Table 1 shows the vote share of the main Opposition party one year after each general election and whether the party went on to win the following election. The highest ‘one year out’ percentage was Labour’s 42 per cent in 1980, while the lowest was the Conservatives’ 33 per cent in 1998. Recent polling has shown Labour on around 27 to 33 per cent of the national vote.

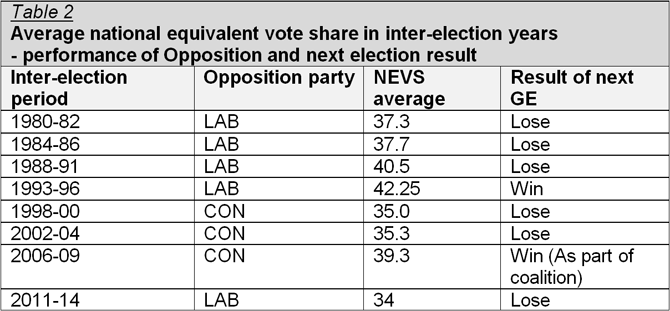

Table 2 examines the performance (in terms of NEVS) of the main Opposition party in local elections in the three or four years between each general election. This measure is a test of support for the Opposition in a series of local election cycles. There are no examples of an Opposition winning a general election with an average NEVS of below 39.3 per cent in the previous three or four years. Indeed, the Conservatives did not win the 2010 election outright although they were the largest party. Labour’s performance between 1988 and 1991, a NEVS of 40.5 per cent, proved insufficient to win in 1992. Looking ahead, Labour would likely need to have a NEVS average of 39 per cent or above between 2016 and 2019 if they are to have much hope of winning in 2020.

What are the key local election contests?

Below is a summary of the key local election contests by party. The analysis looks at councils where there is a possibility of a change in political control and/or where the result casts light on the wider political picture. Of course, local elections are primarily about local issues but they nevertheless also provide evidence about the state of the parties at the time of the election and, as demonstrated above, they are important in terms of how they often resemble subsequent general elections.

Conservatives

The Conservatives will aim to hold all their current councils and to gain control of some currently Labour-held councils such as Southampton and Harlow. If they are able to achieve such a result, to keep the councils they currently control, and add new councils in the areas of important marginal Parliamentary seats, then the party will have had a positive result. If they are able to get a national equivalent vote share in the range 36-38 per cent the party has recently polled, this would represent a positive result for the Conservatives.

Key contests: Thurrock, Swindon, Crawley, Watford, Welwyn Hatfield, Woking, Trafford

Labour

For the opposition Labour party the aim must be, at least, to consolidate its results from the previous elections to these seats in 2012 and also be looking to ensure that the party does not lose control of any council that it currently controls. It needs to perform strongly in Milton Keynes, Plymouth, Southampton and Thurrock as such places are key indicators (in terms of marginal seats) for the next general election. In order to demonstrate Labour has made gains amongst potential support it should look to win a significant proportion of the thirteen seats up for election on Norwich council. If Labour can achieve a national equivalent vote share close to the 39 per cent it achieved in 2012 that would be positive result and would beat its recent national polling numbers which have been below that level.

Key contests: Thurrock, Norwich, Exeter, Plymouth, Southampton

Liberal Democrats

Can the Liberal Democrats make gains from the Conservatives to reclaim some ground? The party needs to perform strongly in places such as Stockport, Milton Keynes, Thurrock and Watford to demonstrate a solid revival. If the party does reasonably well, it will be interesting to see from which of the other parties they gain most votes. Are they able to take votes from the Conservatives to mount a national fight back? Can they take votes from Labour at a time when the party has internal problems?

Key contests: Thurrock, St Albans, Norwich, Stockport, Watford

UKIP

The May 2106 elections are also important for UKIP. After failing to convert nearly four million votes in to more than a single parliamentary seat at the May 2015 general election, UKIP finds itself fighting local elections just seven weeks before the EU referendum. UKIP’s primary issue will thus be at the forefront of voters’ minds. UKIP achieved 13 per cent of the vote share in 2015, and as much as 22 per cent of the national equivalent vote in 2013. The extent to which they can reach such numbers in 2016 will go some way to demonstrating whether they can prosper as a challenger party in the longer term.

Key contests: Thurrock, Harlow, Redditch and Rushmoor

____

This article was originally published on GovBlog; for the latest analysis of 2016’s electoral contests, go to UK Elections 2016. It represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Tony Travers is a Visiting Professor in the LSE Department of Government and Director of LSE London.

Tony Travers is a Visiting Professor in the LSE Department of Government and Director of LSE London.

Martin Rogers is a recent graduate of the Department of Social Policy at the LSE and host of the LSE Department of Government’s video series The HotSeat. He tweets @MNBRogers

Martin Rogers is a recent graduate of the Department of Social Policy at the LSE and host of the LSE Department of Government’s video series The HotSeat. He tweets @MNBRogers

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

England’s 2016 local elections: an indicator of the national political picture? https://t.co/6APPbSSkx5

[BLOG] #UK: Key races by party in local elections. Can they forecast the nat’l political picture? https://t.co/prazH1hnbY @democraticaudit

Really shocked that you ignored the Greens altogether. Ot is popular and well respected.

England’s 2016 local elections: an indicator of the national political picture? https://t.co/PUNJHBdG1q

England’s 2016 local elections: an indicator of the national political picture? https://t.co/xzLZ7qd7p7 https://t.co/RNvLlZ2pOK