Scottish election 2016: disaster for Labour, reality check for the SNP – and the Tories are back

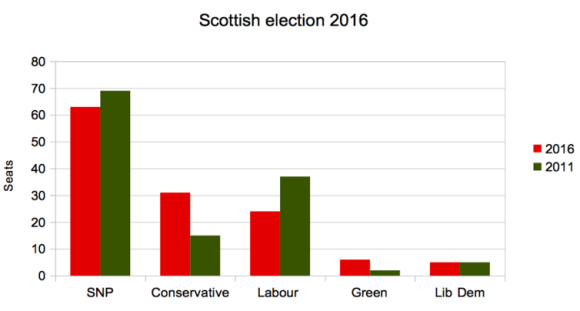

Craig McAngus offers an overview of the fallout of yesterday’s Scottish Parliamentary Elections, which saw the SNP fall short of a majority and a surprisingly strong Conservative revival.

Missing out on the majority puts a dampener on recent success. Credit: Ewan McIntosh CC BY-NC 2.0

The 2016 Scottish election was meant to be a foregone conclusion. Nicola Sturgeon’s SNP was expected to achieve another majority in a repeat of 2011, but it hasn’t happened. The party is the clear winner, securing a historic third term, but two seats short of the majority line. It didn’t quite win as many constituencies as it hoped, and the regional-list vote didn’t deliver enough seats to get the SNP to the magic 65.

The other big surprise is the scale of the Conservative revival. The polls were predicting a tight race between Labour and the Conservatives for second place, although most commentators believed that Labour would just about hold on to its position as the largest opposition party. As things have transpired, Labour had a terrible night and now finds itself as Scotland’s third party. Ten years ago – even five years ago – such a thought would have been inconceivable. Ruth Davidson’s Conservatives are now the official Holyrood opposition, with seven seats more than Labour. So what happened? As with any election, the dust has to settle and the result picked over in greater detail. But a few patterns have emerged.

So what happened? As with any election, the dust has to settle and the result picked over in greater detail. But a few patterns have emerged.

Labour is decimated

In areas that have traditionally been considered Labour heartlands, the SNP has done very well and Kezia Dugdale’s Labour party very badly. In Glasgow, for example, the SNP has secured a clean sweep of constituency seats and increased its majorities in the seats it won in 2011. In that city, as well as Lanarkshire, Renfrewshire and Fife, we have seen a similar pattern to the UK election of 2015. Patrick Harvie, co-convenor of the Scottish Greens, even knocked Labour into third place in Glasgow Kelvin.

Barring a few exceptions, it has been the SNP that has come out comfortably on top. Labour’s Jackie Baillie narrowly held Dumbarton, the constituency which houses the UK’s Trident missile system; and former leader Iain Gray narrowly held on to East Lothian as he had done in 2011. Edinburgh Southern was also won by Labour, local factors playing a key role there as they did at last year’s general election – the equivalent Westminster seat is Labour’s only one in Scotland. On the whole, however, the trend for the SNP replacing Labour as the party of Scotland’s working classes has continued unabated. In all, Labour lost 13 constituency seats to be left with just three – one fewer than the Lib Dems.

Labour gained some solace from Scotland’s eight regions, which offer a route for parties to gain seats to counter the disproportionality of first-past-the-post constituencies. It picked up four seats in Glasgow this way, but Mid Scotland and Fife returned them only two list MSPs despite the party winning no constituencies in the region. Lothian and Highlands and Islands also proved disappointing, returning two Labour MSPs on both lists.

The Conservatives are back

The story of the night has been the performance of the Conservatives in constituencies across Scotland. As results from Glasgow and the surrounding area came in, it was clear the party was going to make gains, increasing its share of the vote by around ten percentage points in some seats where it has struggled in recent decades. The Conservatives also made significant gains from Labour in Eastwood and Dumfriesshire and from the SNP in Edinburgh Central and Aberdeenshire West. Only in the areas of Liberal Democrat gains did the Conservative share of the vote fall. The Conservatives took seven first-past-the-post seats, including their leader Ruth Davidson in Edinburgh Central.

They did well in the list seats, too. They won three MSPs in Central Scotland, by no means a region that is typically sympathetic to the Conservatives, and four in North East Scotland, helping keep the SNP off the list altogether. The party also won two seats in the Glasgow region and three in Highlands and Islands. Nationally, the party has increased its share of the vote by 8.1 points to 22%, only 0.6 points behind Labour.

The Greens

The lists meanwhile helped the Scottish Greens to overtake the Liberal Democrats to become the fourth party of Holyrood, with six seats. Added to the SNP seats this does mean that the pro-independence parties retain a majority.

Yet the Greens are one MSP short of their 2003-07 heyday, and have achieved fewer than some polls were predicting. They had a slightly disappointing showing in Glasgow by managing only one MSP in the form of Patrick Harvie, but in Lothian they picked up two seats, as well one in both Mid Scotland and Fife, Highlands and Islands and West of Scotland.

Despite another disappointing night in Scotland for the Lib Dems, there were a couple of surprises. Aside from holding both Orkney and Shetland, the party managed to gain two seats from the SNP. In North East Fife, the party’s leader, Willie Rennie, ran out the comfortable winner, while the party also won Edinburgh Western. In both seats there appears to have been significant tactical voting, with the Liberal Democrats likely benefiting from Conservative defectors. Meanwhile, predictions that UKIP might pick up a seat came to nothing.

The big picture

The election seems to have reflected the divisions in Scotland over the constitution and class. In areas that are more deprived and traditionally working class and which had a high Yes vote in the independence referendum, the pattern is broadly strong support for the SNP coupled with decline in the Labour vote.

In areas that are more middle class and which voted No in the referendum, the Conservatives have done particularly well apart from a couple of exceptions, namely the Liberal Democrat gains on the mainland. The Conservatives’ framing themselves as a firm unionist opposition to the SNP appears, at least on the surface, to have had some impact. Within this structural fusion of class and constitutional politics, Scottish Labour is struggling to articulate a vision that fits into this new reality.

The SNP will seek to govern as a minority administration, like it did in the 2007-11 parliament. This opens up opportunities for the other parties to do deals in return for supporting the government’s legislation. Although on the face of it one would think the Greens would be the natural party for the SNP to do business with, there is quite some distance between them on issues such as taxation.

During the 2007-11 parliament, the SNP did quite a few deals with the Conservatives – passing the budget in return for increased police numbers, for example. It will be interesting to see to what extent we see a repeat this time around – and whether the nationalists continue to treat Labour as their primary enemy. And although the result is something of a disappointment for the SNP, it must be remembered that the Scottish parliament was designed to be a place where overall majorities were pretty much impossible. We will probably look back on the 2011-2016 parliament as an aberration.

Craig McAngus is a Lecturer in Politics at the University of Aberdeen

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Scottish election 2016: disaster for Labour, reality check for the SNP – and the Tories are back https://t.co/dOItWUOrwK

Scottish election 2016: disaster for Labour, reality check for the SNP – and the Tories are back https://t.co/xuOvDNrdP6

Scottish election 2016: disaster for Labour, reality check for the SNP – and the Tories are back https://t.co/VLSZxUI9AU

@democraticaudit 31 Tories: a No vote dividend from, and for, Labour.

@JonasHinnfors @UlfBjereld Seen this? Suggests SNP took w/c while Tories became main unionist party https://t.co/i73wmUgmDs

Scottish election 2016: disaster for Labour, reality check for the SNP – and the Tories are back https://t.co/AjSTczQK9E

#Scottish #parliament designed for overall #majorities pretty much #impossible. 2011-2016 probably #aberration. – https://t.co/361BwEgAhZ.

#SP16 big pic v> @democraticaudit https://t.co/WI3k63PzrD https://t.co/iauau5cyji

Scottish election 2016: disaster for Labour, reality check for the SNP – and the Tories… https://t.co/4JizBLuAsw https://t.co/SxEY3C2yCs