Why voters do not (always) punish government parties for corruption

Fighting corruption is a vital aspect of good governance. Yet, it is also a highly persistent phenomenon, indicating that tackling corruption is not always at the top of incumbent’s agenda. One way to solve this problem is to engage in corruption performance voting; that is, to use elections to punish incumbents for high levels of corruption. But do citizens actually engage in this kind of voting behavior? Alejandro Ecker, Konstantin Glinitzer and Thomas M. Meyer show that while some voters do engage in corruption performance voting, the segment of voters that are willing to hold incumbents accountable is limited by their partisan preferences, their expectations about future governments, and by the characteristics of the country they live in.

Credit: pushkar v CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Bribery, the embezzlement of public funds, misuse of public party funding, and clientelism are all among those corrupt practices whose severe detrimental effects on the economy and society are well documented. Despite these negative effects, corruption is a relatively persistent phenomenon. Are government parties punished for their poor performance on fighting corruption? In a recent study, we link citizens’ perceptions of the level of corruption in their country with their reported voting behavior. The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) provides excellent data to study corruption performance voting across counties. For 20 European democracies we identified the parties that were in government and analysed whether citizens’ perceived level of corruption influences their choice to vote or not vote for one of the incumbent parties.

Our main finding is in general supportive to the notion of electoral accountability: citizens punish incumbent parties if they perceive corruption to be high and reward the incumbent if they perceive corruption to be low. There are, however, important limitations to this pattern. In particular, we identify three key characteristics that make citizens less likely to engage in corruption performance voting.

The first significant constraint is citizens’ overall orientation towards the incumbent parties. Corruption is after all only one element citizens might care about when voting. Think about an individual who has strong ties towards one party, as it has been the case in most West European countries since the end of WWII. These voters ‘feel close to’ a particular party and are rarely willing to vote for another one. In contrast, non-partisans (or independents) lack these strong predispositions, and thus even small differences in their perceived party performance can have significant effects on their vote choice.

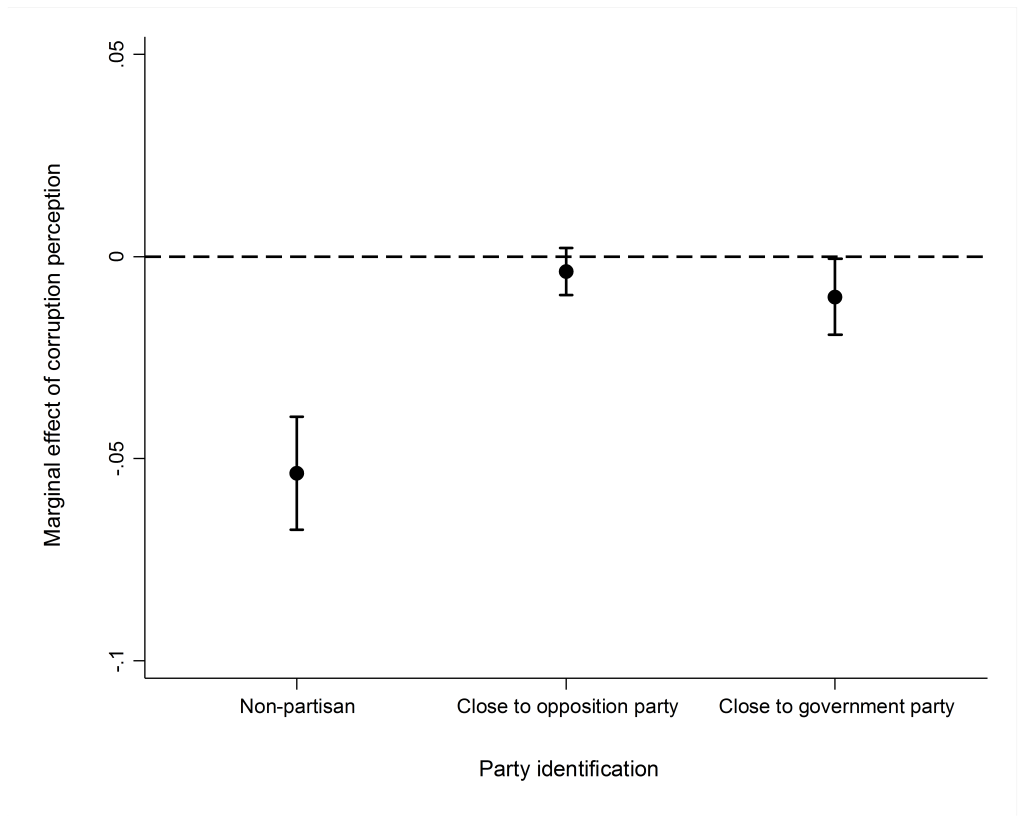

Corruption perception effect depending on party affiliation

Note: This figure shows the estimated marginal effect of a one-unit change in corruption perceptions on the probability of incumbent voting for non-partisans, voters feeling close to an opposition party, and voters feeling close to a government party. Dots indicate point estimates, the vertical lines denote 95% confidence intervals.

Interpretation of this graph is not easy, but one can think about it as comparing two groups: one consists of independents and one of individuals who feel close to the government party (leaving voters feeling close to opposition parties aside for now). The dots in the graph then indicate how higher levels of perceived corruption affect the likelihood of both groups to vote for the incumbent (the line above and below each dot suggest uncertainty due to random variations). As can be seen, non-partisans who perceive corruption to be high have a lower probability of voting for the incumbent than the non-partisans who think corruption is low. This suggests that perceiving corruption as high makes them less likely to support the incumbent. Among the partisan voters, however, the probabilities hardly differ. Apparently, the level of corruption does not influence voting if voters feel close to the incumbent.

The second important constraint refers to citizens’ expectations about alternatives to the current government. Some people think that who is in power actually doesn’t make a huge difference. In fact, many turnovers in government are partial as some parties of the ‘old’ government are also included in the ‘new’ one. Even if the party composition changes, some voters have the impression that parties are all alike and thus, ‘throwing the rascals out’ only means to bring new rascals in. Thus, only citizens who believe in the changing effect of government turnover do actually engage in corruption performance voting.

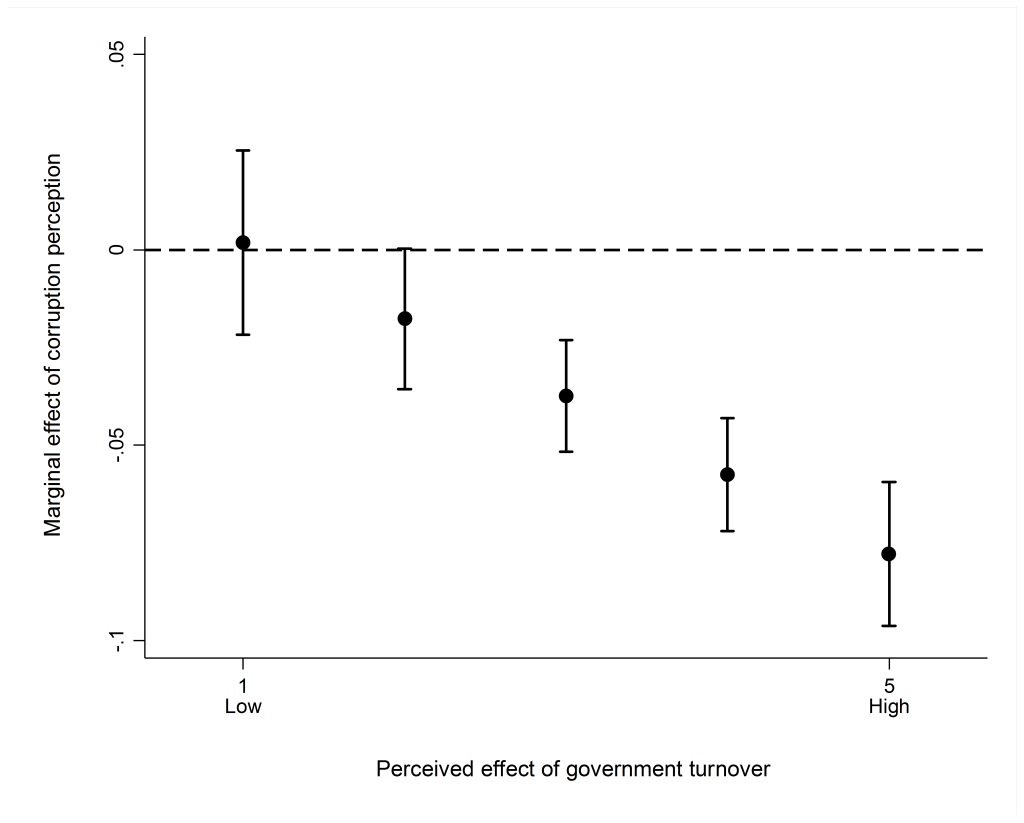

Corruption perception effect depending on effect of government turnover

Note: This figure shows the estimated marginal effect of a one-unit change in corruption perceptions on incumbent voting, conditional on the perceived effect of government turnover. Dots indicate point estimates, the vertical lines denote 95% confidence intervals.

This figure can be interpreted in the same way as the one above, only that the independent/partisan group has been replaced by groups consisting of people who agree or disagree with the statement that ‘it makes a difference who is in power’. The higher the agreement to this statement, the more likely citizens are to engage in corruption performance voting.

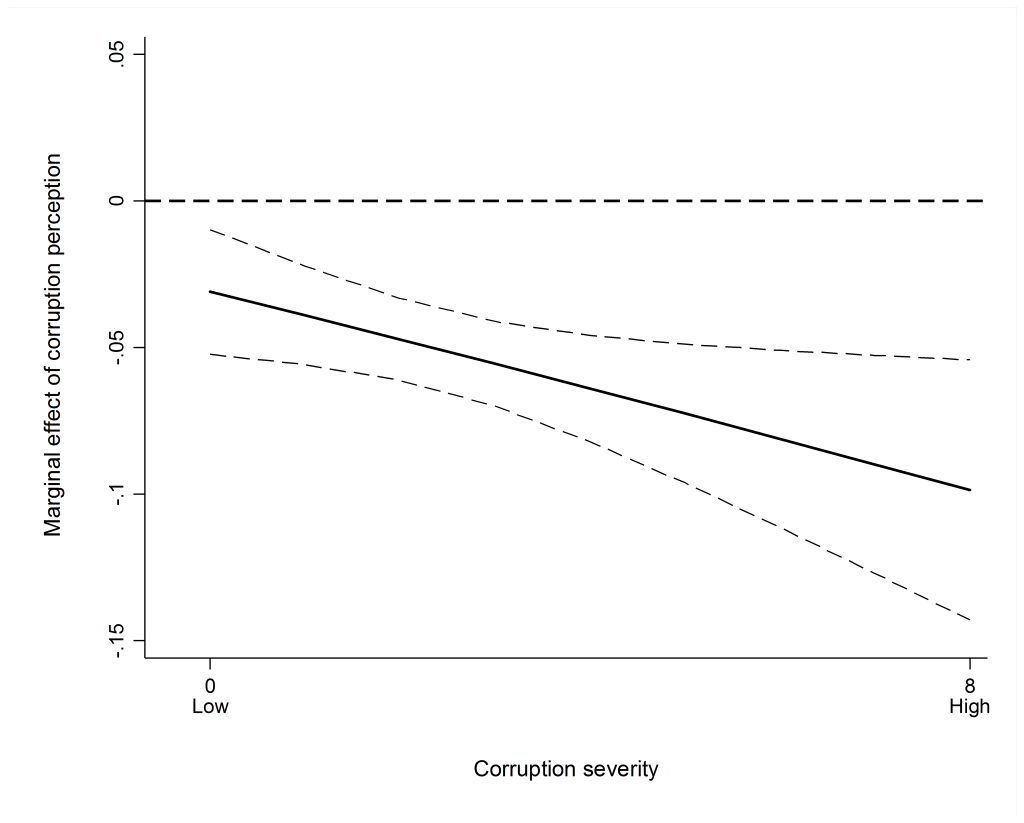

Both these constraints are visible across Europe. However, as a comparison of European countries shows, some countries are much more prone to corrupt elites than others. Think for example about Bulgaria, in which corruption is a pressing concern for many citizens, and Germany, in which corruption is a much less salient topic. Thus, citizens in high corruption contexts might be more inclined to use their vote to bring corruption down. To understand this process we moved from comparing individuals and their attitudes (such as partisanship) to the electoral context and analysed how the country characteristics influence individuals’ voting behavior. We measure the severity of corruption using the corruption performance index (CPI) provided by Transparency International. We found that the citizens place more importance on their corruption perception in contexts where corruption is a highly salient, severe topic. In contrast, voters pay relatively little attention to the level of corruption in those countries where corruption is generally a relatively unimportant issue.

Corruption perception effect depending on corruption severity

Note: This figure shows the estimated marginal effect of a one-unit change in corruption perceptions on incumbent voting, conditional on corruption severity. The solid line indicates the estimated effect, the dashed lines denote 95% confidence intervals. The empirically observed maximum on the CPI 0-10 scale is 7.2.

Corruption is a highly persistent phenomenon and citizens can only rely on the crude tool of voting to express their dissatisfaction with current levels of corruption. Furthermore, the segment of voters that are willing to hold incumbents accountable is limited by their partisan preferences, their expectations about future governments, but also by the characteristics of the country they live in. These factors together suggest that citizens might have a chance in influencing what their governments do to tackle corruption – but also that the fight against corruption is by no means an easy one.

—

This post represents the views of the author, and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Alejandro Ecker is a pre-doctoral researcher at the Department of Government, University of Vienna.

Alejandro Ecker is a pre-doctoral researcher at the Department of Government, University of Vienna.

Konstantin Glinitzer is a pre-doctoral researcher at the Department of Government, University of Vienna.

Konstantin Glinitzer is a pre-doctoral researcher at the Department of Government, University of Vienna.

Thomas M. Meyer is Assistant Professor at the Department of Government, University of Vienna.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Why voters do not (always) punish government parties for corruption https://t.co/4IYi8Dk5Mm

Great piece by @democraticaudit on why voters don’t (always) punish government parties for corruption. See here: https://t.co/uTl0xoy9Pu

Why voters do not (always) punish government parties for corruption – Ecker, Glinitzer and @ThomasMMeyer, using CSES https://t.co/m75svV7NxR

Why voters do not (always) punish government parties for #corruption https://t.co/IZrOEfFoG9

Why voters do not (always) punish government parties for corruption https://t.co/8DCFOLeZwD

Study on how voters react to government corruption

https://t.co/LBOEe8JLCe

#corruption

Why voters do not (always) punish government parties for corruption https://t.co/TC9vJFbS0w

Why voters do not (always) punish government parties for corruption https://t.co/M2CWQ7ykSn

Interesting article about fighting government corruption with performance voting: https://t.co/9JLvcXrrNt

@democraticaudit

It seems to me that what this says most of all is that …

People have become so used to tales of corruption, that the marginal impact is tiny.

Why voters do not (always) punish government parties for corruption https://t.co/MVAbcmhZDF https://t.co/zCU9tiM3RJ