What next for the Greens? The Green Party after Natalie Bennett

Natalie Bennett recently announced that she will not seek re-election for a third term as leader of the Green Party. James Dennison evaluates Bennett’s leadership, as well as the impact that the negative press coverage she received had on the party. Thanks to the party’s growing membership under her leadership – having attracted voters from Labour and from the Liberal Democrats – the new Green leader will have to perform a balancing act in articulating the party’s future direction.

Credit: Jason CC BY-NC 2.0

Natalie Bennett’s four years as Green leader – probably the most successful in the party’s history – will come to an end at the party’s September conference. During Bennett’s two terms the party’s membership more than quadrupled from 14,000 to around 65,000 – making it England’s third largest party. Its vote share also rose from less than one per cent to over four per cent in England and Wales at the 2015 general election, and the party received unprecedented media attention as well as inclusion in the pre-election televised leaders debates.

In spite of the party’s successes, media evaluations of Bennett as Green leader have been either lukewarmor outright negative, with the FT concluding that Bennett “failed to deliver the electoral breakthrough that had been hoped for.” In particular, journalists have focused on a number of ‘car crash’ interviews with Natalie Bennett that robbed the party of credibility with the electorate and led to its slide in the polls from double figures shortly after the New Year to around 5 per cent during the ‘short campaign’ prior to the General Election.

Bennett’s shortcomings closely mirrored those of the party as it attempted to transition from an inward-looking minor party into an externally facing, electorally focused mid-sized party. As I show in my upcoming book, The Greens in British Politics, Green members almost universally praise their soon-to-be former leader for internally managing the party and galvanising its members. Indeed, her endless tours of the country helped lay the groundwork for the ‘Green Surge’ in late 2014 and early 2015 that saw a sudden increase in party members, as the public interpreted the Greens’ then exclusion from the television debates as unjust. During this period, the media took on an enthusiastic approach to the Greens as a potential ‘UKIP of the Left’, partially thanks to Bennett’s push to give the party relevance and visibility as England’s only ‘anti-austerity’ party.

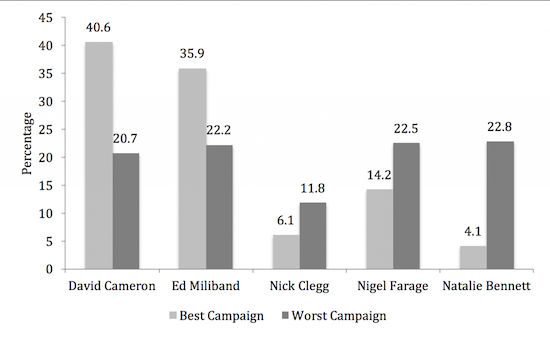

Once the party was admitted to the debates, the media’s tone suddenly shifted towards the sort of tough scrutiny that other established parties were far more used to. Whereas Bennett had done a fine job of enthusing her already sympathetic members, she was unable to defend her party’s endless list of policies that had been voted for at party conferences over the previous 40 years, which in the name of party democracy were made publicly available. In response to the resulting criticism, the Greens took on a more risk-averse approach that focused primarily on protest and principle, rather than policies or personality. Bennett took much of the blame both inside and outside of the party for the resulting weak Green campaign that undermined some of its impressive earlier progress (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Which party leader has had the best and worst campaign?

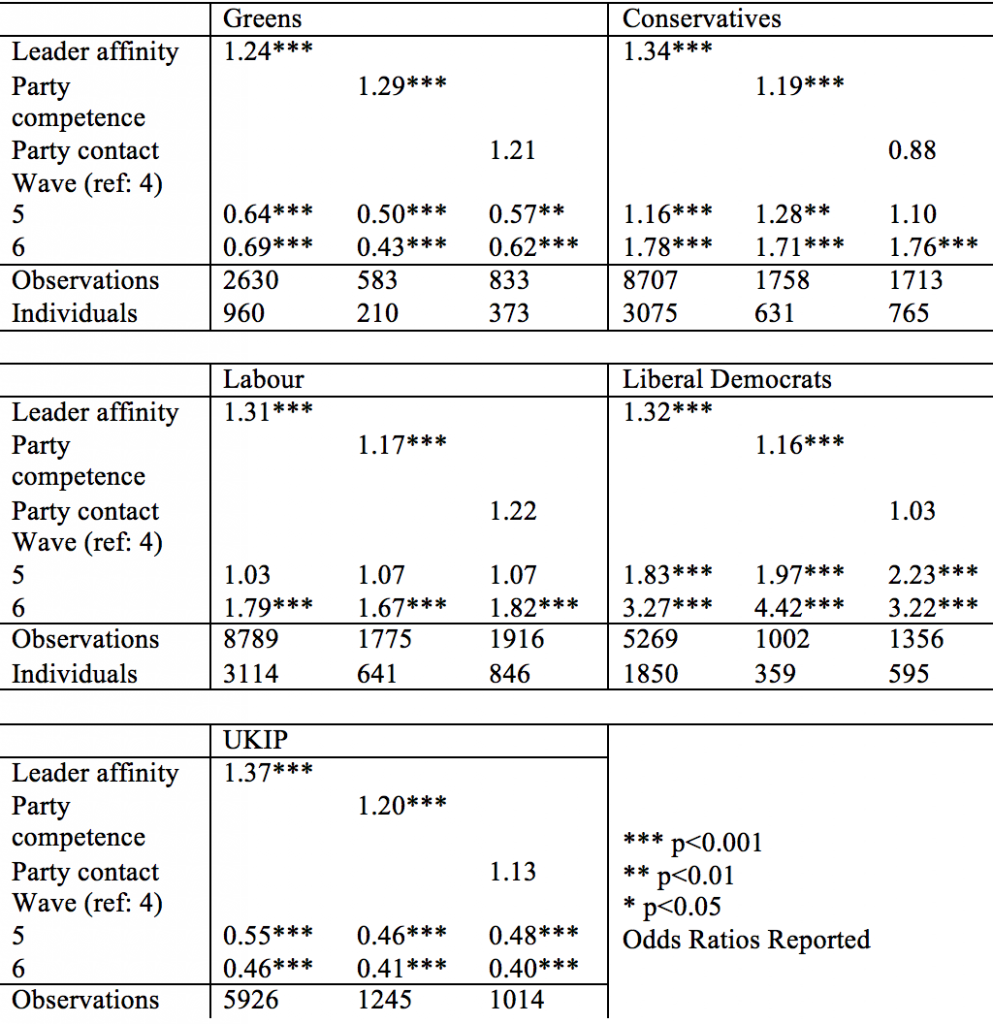

However, the Greens should take caution before assuming that by electing a new leader they will exorcise all of the ghosts of Bennett’s ‘car crash’ interviews. Indeed, there is some evidence (see here) to suggest that, compared to the other four English parties, the Greens’ vote was relatively unsusceptible to how much voters’ liked their party’s leader. Instead, the Greens’ vote was more vulnerable than any other party’s to perceptions of (in)competence, something that is unlikely to be salvaged simply by electing a new leader. In short, in order to progress, the Greens need a leader that will make them seem capable, rather than just likeable.

What next for the Greens?

Thanks to its increase in resources and exposure from the Green Surge, the party is now, somewhat precariously, a member in the second-tier of Britain’s figured party system – alongside UKIP and the Liberal Democrats. For the first time in 2015 they were able to attract major donations, peal significant numbers of anti-establishment voters away from Labour and anti-austerity voters from the Lib Dems, build a significant, professional operations and communications structure and, if not entirely successfully, paint themselves as the alternative or ‘real’ opposition to the major parties. They were also able to attract voters via a small number of policies – nationalised rail, free university tuition, a living wage – that had been avoided or abandoned by the major parties over the years, under the umbrella of anti-austerity.

How will the party retain members, resources and relevance – all of which I argue in The Greens in British Politics were gained, at least in part, thanks to their monopoly in England over an anti-austerity narrative – now that Jeremy Corbyn is leader of the Labour Party? The election of Corbyn need not be the disaster for the party that some have predicted. Of 2015 Green voters, over half voted for the Liberal Democrats in 2010 whereas less than 15 per cent voted for Labour – few Greens have a habit of voting Labour. Moreover, though Corbyn’s leftist, radical credentials are clear, many of his MPs are centrists. With careful targeting the Greens can exploit these divides, particularly in constituencies with favorable Green demographics.

The Greens can also take solace in noting that Corbyn and his team may suffer many of the same problems as the Greens prior to 2015 – a fairly unpopular leader coupled with a perception of incompetence. To capitalise on a new political context, which so far seems to include a struggling Liberal Democrat party and a possible 2020 Conservative victory by default, the Greens will have to perform a careful balancing act of retaining their overarching anti-austerity narrative but at the same time positively articulating policies that reflect their values of ecological well-being and improved quality of life. Relying on appeals to protest and principle – in the form of opposition to spending cuts – is unlikely to be enough for the party any longer.

Immediately after Bennett’s announcement, betting markets placed Caroline Lucas, the party’s highly popular and respected MP for Brighton Pavilion, as odds-on favorite to be the next Green leader. Lucas, who had led the party until 2012, resigned in order to focus on defending her seat at the general election while having a party leader with a carte blanche to campaign around the country.

This was a successful formula for the party, up to a point. Lucas, who would certainly win any leadership contest, is now left with a conundrum. With a more comfortable majority in her Brighton seat and with the tantalising prospect of future participation in leaders’ debates – in which she was keen to represent her party even when she was not its leader – Lucas will find it difficult to resist the opportunity to give her party much-needed credible and popular leadership.

On the other hand, if a leadership candidate can be found that seems capable of appealing to voters, Lucas may again opt for the best-of-both-worlds approach of having a party leader free to campaign nationwide while she defends Brighton. Some Greens have already pointed out the need to build up the profile of others in the party. After the last few years, much of the party’s decision will depend on the perceived ability of any would-be leader to appear convincing and competent when faced with the immense media scrutiny that all parties face during general election campaigns. Far more than before, the new Green leader will be chosen by their ability to perform under the media’s spotlight.

—

This article was originally published on the LSE British Politics and Policy blog. Read the original article.

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting. ![]()

—

James Dennison is a Researcher at the European University Institute in Florence. His book The Greens in British Politics will be published by Palgrave in Summer 2016. He tweets at @jamesrdennison.

James Dennison is a Researcher at the European University Institute in Florence. His book The Greens in British Politics will be published by Palgrave in Summer 2016. He tweets at @jamesrdennison.

Appendix

Fixed effects logistic panel models of the effects of leader affinity, party competence and party contact on voting for each party (source: British Election Study, 2015)

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

What next for the Greens? The Green Party after Natalie Bennett https://t.co/Hr8j4YYRop

Great article @JamesRDennison on next steps (& leaders?) for @TheGreenParty Party after @natalieben https://t.co/nc3TLNwtwm @democraticaudit

What next for the Greens? The Green Party after Natalie Bennett https://t.co/NprvQzNgJd

What next for the Greens? The Green Party after Natalie Bennett https://t.co/WQBZVSGedn

What next for the Greens? The Green Party after Natalie Bennett https://t.co/sJs3QooX04

What next for the Greens? The Green Party after Natalie Bennett https://t.co/pMoobxhI47