How democratic is the UK’s participation in the European Union?

As part of the 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Stuart Brown examines the extent to which the UK’s participation in European and international institutions affects the quality of UK democracy. Overall, while some positive reforms have taken place at the European level since 2012, the UK’s uncertain relationship with the European Union and a general lack of transparency in international organisations remain key areas of concern.

Credit: Bobby Hidy CC BY-SA 2.0

What does democracy require for participation in cross-national or international organisations?

- Cross-national or international organisations are very rarely controlled via directly democratic procedures (e.g. population-proportional representation in decision-making bodies). Most such bodies rely on reaching relatively high levels of agreement amongst member states, plus an ethos of respecting the fundamental interests and autonomy of states.

- Still, so far as possible, cross-national bodies should allow for citizens’ views and interests to be gauged and represented directly, not just indirectly by their member state government.

- Cross-national and international organisations should be fully transparent so as to enable proper scrutiny of their decision-making processes by citizens in the member states covered by a treaty or international institution.

- A country’s participation in international organisations should not serve to undermine or weaken democratic processes operating at the level of national politics. Changes of major policies, treaties or how supra-national institutions operate should require an appropriate level of active consent of citizens in the member states.

- National elites dealing in cross-national bodies inevitably must play a ‘two-level game’, negotiating for the best feasible deal at the international level in one way, and justifying their actions to their national electorates in a somewhat different fashion. However, it is vital that elites listen to their public, and that effective (truthful) accountability is maintained.

- The managers and staffs of cross-national and international organisations should be held accountable for their actions in detail, with effective mechanisms in place to ensure that they uphold legal and ethical responsibilities.

Recent developments

The UK is a member of many important international organisations and alliances, especially the European Union, NATO (the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation), the World Trade Organisation, and so on. These external links have long been recognised as having relevant potential impacts on the quality of British democracy. This impact can be both positive, where joining an international organisation may allow the UK to exert influence over global decisions that affect British citizens. Alternatively, they may be negative, should participation in international decision-making processes weaken the UK’s democratic framework, e.g. by narrowing the range of policy debates or options, or by leading to elite collusion to exclude ‘unwise’ or ‘infeasible’ choices from the electorate’s consideration.

The 2012 Democratic Audit noted that a lack of transparency and accountability in the decision-making processes used in organisations such as the European Union and the World Trade Organization posed a tangible threat from a democratic perspective. The audit also drew attention to the possibility that reductions in the budget of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) could undermine the country’s capacity to secure influence over international decisions that affect the UK. Despite some key developments and reforms which have taken place since 2012, these threats continue to be relevant.

The most significant developments have occurred in relation to the UK’s membership of the European Union. David Cameron announced in January 2013 that he would pursue a renegotiation and submit a new settlement to the public as an ‘in/out’ referendum should the Conservatives win a majority at the 2015 general election. Following the election, negotiations took place, with a final agreement reached in the European Council in February 2016.

There were two key elements of the Cameron renegotiation for British democracy. First was the provision of a ‘red card’ procedure, under which national parliaments would be able to challenge EU proposals if 55 per cent of parliamentary chambers registered opposition. Second, there were reforms aimed at safeguarding the UK’s position from further integration into ‘ever closer union’, and especially not into the Eurozone. While in principle the red card offers an extra element of accountability, previous research has demonstrated that the system would likely be in play in only a very small number of cases. Similarly, with regard to the Eurozone, the deal would allow the UK to delay, but not to block, certain proposals stemming from Eurozone states.

Beyond the renegotiation, other EU-wide reforms have also taken place since the previous audit. The 2014 round of European Parliament elections included, for the first time, provisions to ‘elect’ the President of the European Commission (the EU’s central bureaucracy, with powers to initiate new policy proposals) via the so called Spitzenkandidaten process. This entailed each of the main European party families nominating a presidential candidate prior to the election. The candidate from the parliamentary group that then received the most support from voters would be appointed as the next President. There were some doubts as to whether the process would be accepted by national governments. But in the end the nominee from the European People’s Party (EPP), Jean-Claude Juncker, was duly appointed as Commission President following the EPP getting the most votes in the election.

The Spitzenkandidaten process had the potential to address two of the most commonly cited arguments in the context of the EU’s democratic deficit: the indirect appointment of the European Commission, and the lack of engagement or low turnout in European Parliament elections. Judged by these standards, the impact on UK democracy was fairly low. Turnout in the election in the UK was marginally higher than it had been in the previous election in 2009 (35.6 per cent in 2014 as opposed to 34.7 per cent in 2009), but still well below UK general elections. British press or broadcast coverage of the candidates for President was minimal, unlike that in some other EU countries. Moreover, the winning candidate was nominated by a European party (the EPP) that has no British affiliated member (since the Conservatives left it). Alongside Hungary, the UK was also one of only two states to vote against Juncker’s appointment following the election.

The public vote in the European Council on Juncker’s appointment was, however, a positive development for transparency at the European level, given that EU appointment processes have previously been criticised for taking place in negotiations behind closed doors. Previous research has demonstrated a general increase in transparency in the EU’s Council of Ministers over the last two decades (its main executive body), albeit primarily in areas that attract low levels of political controversy.

Some concerns over transparency and accountability raised in our 2012 audit continue to be relevant. While transparency in the Council of Ministers may have increased, there has been a substantial increase in the number of key decisions made through closed-door negotiations amongst heads-of-government during summits in the confusingly named European Council – for example, this was the main way that decisions were made during the 2008-13 Eurozone crisis, the subsequent Greek debt crisis, and the 2015-16 migration crisis.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|

|

| Opportunities for positive change | Future Threats |

|

|

Uncertainty over the UK’s referendum on EU membership

Taken at face value, the fact that the British electorate will be able to cast a vote on the country’s relationship with the European Union might be regarded as a positive development for UK democracy. The referendum allowed for a clear articulation of the arguments for and against the European Union. It has also potentially facilitated greater engagement from academia, think tanks, and other organisations in communicating the effects of European integration to British citizens.

However, plebiscites of this kind are inherently highly coercive, with no compromises or deliberative softening of issues possible. Thus they are highly imperfect instruments of democracy. Citizens who feel intense support for either side of the issue will see their long-term futures and established rights shaped (perhaps irreversibly) by the decision of a (possibly narrow) majority.

The lasting consequences of the referendum for democracy are more difficult to ascertain. It is easier to envisage the kind of relationship that the UK would have with Europe if citizens choose to remain in the European Union. But ongoing reforms at the European level may still adversely affect the UK’s present terms of membership.

A vote to leave the European Union would also generate uncertainty. Currently, no single model for an alternative relationship with the European Union has widespread support among those actors campaigning to leave. A number of possible options exist, including the negotiation of a ‘Norwegian’ or ‘Swiss’ style agreement that allows the UK to continue to participate in the single market; the negotiation of a less comprehensive free trade agreement such as that concluded between the EU and Canada; or simply relying on World Trade Organization rules to gain trade access to European markets. We also do not know whether the remaining EU countries would wish to impose either a harsh or a soft secession process on the UK.

The open-ended nature of the campaign therefore allows for both a positive and a negative interpretation of how a leave vote could impact on UK democracy. Leave campaigners have argued that by restoring full national autonomy, and re-localizing issues currently fixed in Brussels, leaving the EU would improve British democracy. The danger in this context would be if the UK’s alternative relationship following a leave vote resulted in having to accept many EU rules and requirements while having no voice in what these are. The Norwegian model has long been criticised on this basis, for instance, due to the country implementing EU legislation despite lacking full representation in the EU’s institutions.

The EU’s ‘democratic deficit’

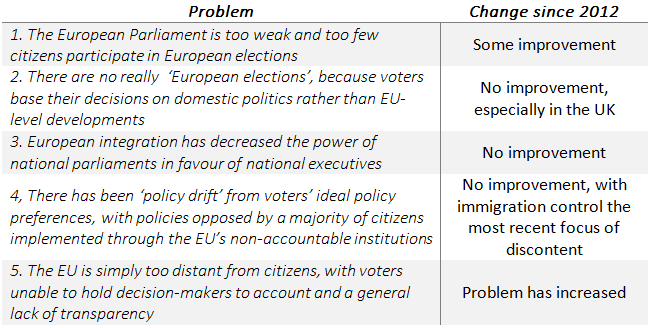

If the UK stays in the EU, there is little consensus on the nature of the ‘democratic deficit’ alleged by Eurosceptics. At least five different critiques of EU democracy can be identified, shown in Table 1. We assesses how each issue has developed since 2012 using this rating system: if steps have been taken to remedy the problem since 2012, but without eliminating the issue entirely, a rating of ‘some improvement’ is assigned; or there could be ‘no improvement’ since 2012; and finally if the situation has deteriorated since the last audit, a rating of ‘problem has increased’ is given.

Table 1: The EU’s democratic deficit and changes since 2012

Note: The five diagnoses of the democratic deficit are adapted from Follesdal and Hix (2006)

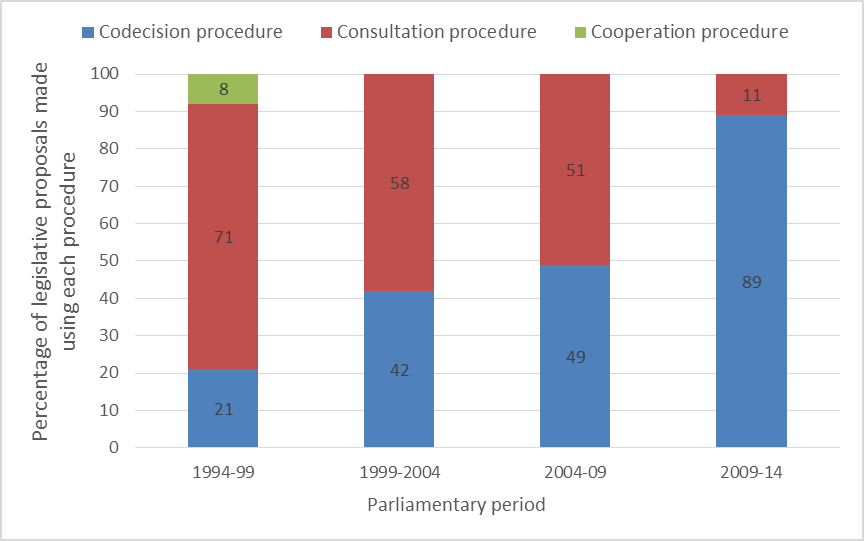

On point 1 there has been some tangible improvement since our 2012 audit. The powers of the European Parliament have significantly increased as a result of the Lisbon Treaty entering into force. In the 2009-14 Parliament, no less than 89 per cent of legislative proposals were adopted using the so called ‘co-decision’ procedure (now called the ‘ordinary legislative procedure’). Under this rule legislation must be jointly agreed between national governments in the Council and MEPs in the Parliament. As Chart 1 below shows, this is a marked increase on previous parliamentary periods, where the bulk of legislation was determined using other procedures, chiefly the ‘consultation’ procedure, in which the Council is not legally obliged to take account of the Parliament’s opinion.

Chart 1: Percentage of legislative proposals adopted using the co-decision (ordinary legislative) procedure

Source: European Parliament

This increase in power has not been matched, however, by an increase in turnout in European elections. Indeed, in the 2014 elections, turnout across Europe fell again, with 17 out of 28 member states experiencing a drop from the previous elections in 2009, although there was a small increase in the UK’s turnout.

On point 2, the power of national executives in relation to parliaments, there has been some modest change for the better. The Lisbon Treaty introduced a ‘yellow card’ procedure (the forerunner to the ‘red card’ that formed part of David Cameron’s renegotiation) which allows for an objection to be issued to an EU proposal by one third of EU parliaments acting in unison. Although initially treated with scepticism, the procedure was successfully used for the first time in May 2012 in response to the so called ‘Monti II Regulation’. It was again used in relation to the establishment of the European Public Prosecutor’s Office and has been used most recently in May 2016 in relation to a revision of the Posted Workers Directive.

Finally, the effects of the Eurozone and migration crises seem to have had adverse effects on EU democracy. In both cases, European Council and Eurogroup meetings have become the focus for decisions of substantial importance for all European citizens. The UK is perhaps less involved on these issues (because it is outside both the Eurozone and Schengen free movement area). But this much greater reliance on closed-door intergovernmental negotiations to produce solutions to crises nevertheless represents a potentially worrying development for EU democracy, if the European Parliament remains less involved and citizens are not given adequate representation.

Conclusion

Whatever the result of the UK’s referendum on EU membership, the country’s participation in cross-national and international organisations will remain an important external factor in shaping the quality of British democracy. Should the UK decide to stay within the European Union, developing greater transparency in decision-making and strengthening the role of national parliaments in the EU’s legislative process offer two obvious routes for alleviating the existing democratic problems at the European level. Alternatively, if the UK opts to leave the European Union, it will be vital to establish a relationship with Europe where British citizens continue to have representation in key international decisions that affect their interests, and can still gain from key rights (for example, to move between EU countries).

This post does not represent the views of the London School of Economics or the LSE Public Policy Group.

Stuart Brown is a Research Associate at LSE Public Policy Group, and a Senior Research Associate at the University of East Anglia. He is the Managing Editor of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy and the author of The European Commission and Europe’s Democratic Process (Palgrave, 2016). He is on Twitter @StuartABrown01

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

https://t.co/jzOfHPns9c

How democratic is the UK’s participation in the European Union? https://t.co/wFMimu9yzs

How democratic is the #UK’s participation in the #EuropeanUnion, asks @StuartABrown01 https://t.co/XK8zAPfYwk #EU #EUref

How democratic is the UK’s participation in the European Union? https://t.co/3tVCd7cGuz

How democratic is the UK’s participation in the European Union? https://t.co/AQglTlWM8i #EURef

How democratic is the UK’s participation in the European Union? https://t.co/3tVCd7uhT9

How democratic is the UK’s participation in the European Union? https://t.co/8XHk7ULwX8 https://t.co/6Ogcyd4zfd