Who will succeed David Cameron? A brief history of takeover Prime Ministers

Following David Cameron’s announcement that he will resign following the EU referendum, Ben Worthy assesses the experiences of Prime Ministers who have taken over mid-term, and considers what can be taken from this as we look forward to the upcoming Tory leadership battle.

Credit: Number 10 CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

David Cameron will not be Prime Minister by October, and is going even earlier than I predicted. So what does the past tell us about who might take over as Prime Minister, and how they might fare? Who, out of these runners and riders, will be next as First Lord of the Treasury?

There’s generally two ways you can become Prime Minister in the UK through (i) winning a General Election (ii) winning a party leadership election (or in the pre-1965 Conservative party being ‘chosen’) to become head of the largest party when a Prime Minister leaves-see this great infographic here.[1]

Whoever sits in 10 Downing Street after David Cameron will be what I’m calling a ‘takeover’ leader, who takes over government by (ii) rather than (i). As the UK Cabinet Manual states:

Where a Prime Minister chooses to resign from his or her individual position at a time when his or her administration has an overall majority in the House of Commons, it is for the party or parties in government to identify who can be chosen as the successor (p.15).

Although often seen as ‘lame ducks’ or less legitimate, remember both Lloyd George and Winston Churchill and Lloyd George, number 1 and number 2 respectively in the highest rated Prime Ministers of the 20th century, got to 10 Downing Street without winning an election.

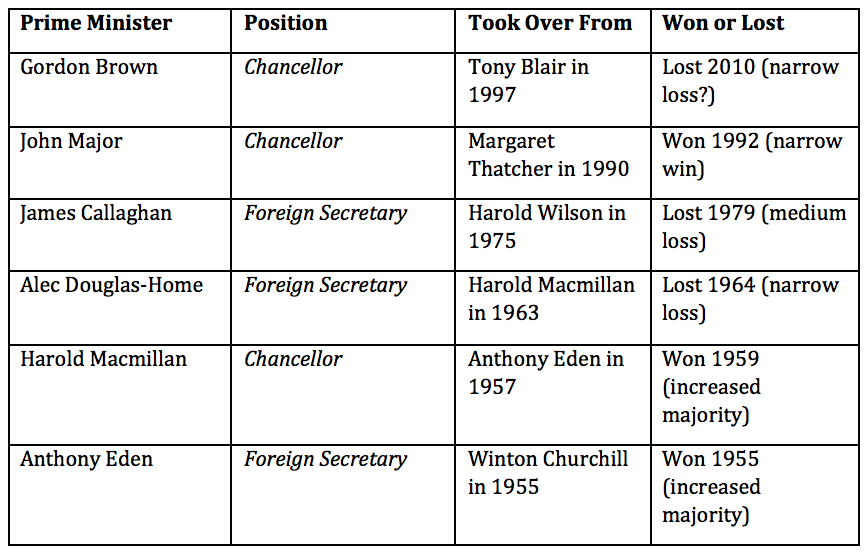

Here’s a table looking at the last six Post-war ‘takeover’ Prime Ministers that sets out who they took over from, their previous position before Prime Minister, and – the all-important question – whether they went on to win the next election.

Takeover Prime Ministers 1955-2010

Interestingly, of the 12 Post-war Prime Ministers almost half were actually takeovers. So how did these takeovers do in the General Elections that followed? It seems there are exactly even chances of winning or losing, as 3 takeovers lost their elections and three won, though drilling down it can be close. John Major had a very narrow win in 1992 and Alec Douglas-Home a surprisingly narrow loss in 1964. What the table doesn’t show is the danger in stepping into Downing Street without an election, which explains why the other 50 % failed to win. Takeover is a risky business even in tranquil times, as this great paper shows.

In terms of who does the taking over now, a superficial look at the table offers good news for Theresa May and Michael Gove and bad news for Boris Johnson. All the takeovers Post-War were already holders of ‘great offices of state’. In fact, 3 were Chancellors and 3 were Foreign Secretaries. This makes sense as it is senior politicians who will have the resources, the reputation and, most importantly, the support in the party to win a leadership election.

The past is not, of course, always a good guide to the future, especially in a Brexit-ing Britain. To be Conservative leader you must make it through a particular bottleneck, as two potential leaders must emerge from the votes of the Conservative MPs for a run-off with the rest of the party. This morning it is very, very unlikely that the next leader will be the (probably) soon to be ex-Chancellor George Osborne. Foreign Secretary Phillip Hammond is, as far as we know, not interested.

The closest ‘great offices’ are Theresa May in the Home Office, whose chances have been talked up until yesterday, and Justice Secretary Michael Gove, who has ruled himself out repeatedly (though so did his hero Lyndon Johnson, many times). However, Boris Johnson, who has no great office but was Mayor of London for eight years, will have a large amount of political capital and has powerfully bolstered his reputation. A Brexit Johnson versus a Eurosceptic May run-off looks likely.

Gauging how ‘successful’ the takeover leaders were is more tricky-the whole question of whether and how a Prime Minister ‘succeeds’ depends on how you measure it. Half of the leaders achieved the most basic aim of winning an election and a number of them not only won but also increased their majority. Beyond this, some are widely regarded as having failed amid crisis, splits and defeats, especially John Major and Gordon Brown. Not all takeovers are failures or lame ducks. Three of the leaders came number 4, 7 and 8 in the academic survey of the top ten Post-War Prime Ministers and Harold Macmillan in particular is widely regarded as a highly capable and astute Prime Minister.

Whoever takes over from Cameron will face deep problems. He or she will be in charge of a ruptured party, and a worrying in-tray of pressing problems. Being prime Minister of Brexit Britain will mean trying to hold together a divided country and Dis-united Kingdom, not to mention overseeing a hugely complex negotiation process. Whoever takes over will need a very healthy dose of fortune and skill to be a Macmillan rather than a Brown.

__

[1] There are other ways but it all gets a bit complicated and constitutional see p 15 of the Cabinet Manual 2.18-2.19. If a government falls and an opposition can muster up a majority then an opposition leader could become Prime Minister without an election (but would probably want to call a General Election soon after). The Cabinet Manual hedges its bets by saying ‘The Prime Minister will normally be the accepted leader of a political party that commands the majority of the House of Commons’.

__

Note: This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

__

Ben Worthy is Lecturer in Politics at Birkbeck College, University of London.

Ben Worthy is Lecturer in Politics at Birkbeck College, University of London.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Who will succeed David Cameron? A brief history of takeover Prime Ministers https://t.co/UJHutl5cNY

via @jrteruel “RT: Who will succeed David Cameron? A brief history of takeover Prime Ministers https://t.co/iM4s7qDA6Z“

Who will succeed David Cameron? A brief history of takeover Prime Ministers https://t.co/GwXDPcdJSd

@Johncraig_ @democraticaudit @PJDunleavy the full article has a look at that..

https://t.co/OiIq40koWn

Takeover Prime Ministers, a brief history. https://t.co/9jC2aCjvox

Who will succeed David Cameron? A brief history of takeover Prime Ministers https://t.co/MwDIV5uBLT

@dianarangel_ Interesante: “Who will succeed David Cameron?” https://t.co/JuiQUac9gE vía mi cuate @gabrielgovela. Para @esteban_is, también.

Who will succeed David Cameron? A brief history of takeover Prime Ministers https://t.co/D74G7udVvb

Who will succeed David Cameron? A brief history of takeover Prime Ministers https://t.co/kTOov3xh0x

.@DigitalpolBirkb rapidly puts pen to paper in @democraticaudit to discuss @Number10gov succession: https://t.co/zylG3AsLUF

[…] Who will succeed David Cameron? A brief history of takeover Prime Ministers. Following David Cameron’s announcement that he will resign following the EU referendum, Ben Worthy assesses the experiences of Prime Ministers who have taken over mid-term, and considers what can be taken from this as we look forward to the upcoming Tory leadership battle. […]

Who will succeed David Cameron? A brief history of takeover Prime Ministers https://t.co/lynnTWaX2B

Who will succeed David Cameron? ‘Takeover’ Prime Ministers and how they fare in office https://t.co/UaDs9ZFkM8 via @democraticaudit

Who will succeed David Cameron? A brief history of takeover Prime Ministers https://t.co/FSLmFliVLm https://t.co/upDY9QmHc4