The ultimate causes of Brexit: history, culture, and geography

Xenophobia, austerity, and dissatisfaction with politics may have contributed to the Brexit vote. But James Dennison and Noah Carl write that, although a number of concerns may have tipped the balance, Brexit was ultimately decided by more than recent events. Here, they demonstrate how the UK has been the least well-integrated EU member state, and so the closer the EU was moving toward political union, the more likely Brexit was becoming.

Credit: Graeme Darbyshire, CC BY 2.0

Since the British electorate voted to leave the European Union, many commentators have sought to explain (and often decry) the referendum’s outcome as the result of a misleading and demagogic Leave campaign,irrational xenophobia, simple racism, an obstinate protest vote, the government’s fiscal austerity policies, a largely Eurosceptic press, or general discontent about the economy. While several of these explanations have at least some merit, we believe they are insufficient. Indeed, they either put too much emphasis on recent events, or mistakenly assume that few Leave voters were motivated by dissatisfaction with Britain’s EU membership per se.

Regarding the former, a recent analysis of internet and phone polls suggests that Leave may actually have had the lead throughout the entire campaign, belying the claim that provocative statements made by Nigel Farage or Boris Johnson exerted decisive sway over prospective voters. Regarding the latter, evidence from the BES internet panel and Lord Ashcroft’s large post-referendum poll suggests that overall national sovereignty may have been just as important an issue for Leavers as immigration, and that austerity hardly registered.

Opposition to Britain’s membership of the EU has fluctuated over the years, but has remained substantialever since the UK joined in the mid 1970s; somewhere between ~30 and ~60 per cent of the British public has always been opposed to EU membership. Of course, the Eurosceptic fraction of the population almost certainly increased as a consequence of the rapid rise in EU immigration, which began in the late 1990s, and the Eurozone debt crises, which precipitated mass unemployment across Southern Europe. Nevertheless, the most important phenomenon to be explained vis-à-vis the referendum result in our view is that a sizable Eurosceptic faction has remained extant in Britain over the last four decades, in contrast to the other countries of Europe.

In The American Voter, one of the seminal studies on voting behaviour, Angus Campbell arranged the myriad factors affecting vote choice within a so-called funnel of causality: ultimate causes – such as structural and historical factors – were placed on the left hand side of the diagram, while proximate causes – such as attitudes to individual policies and candidates – were placed on the right hand side. Similarly, and we show that in a number of important respects, the UK is the least well-integrated EU member state – essentially, the least European country – and that this fact likely stems from certain historical features, which arguably constitute the ultimate causes of Brexit.

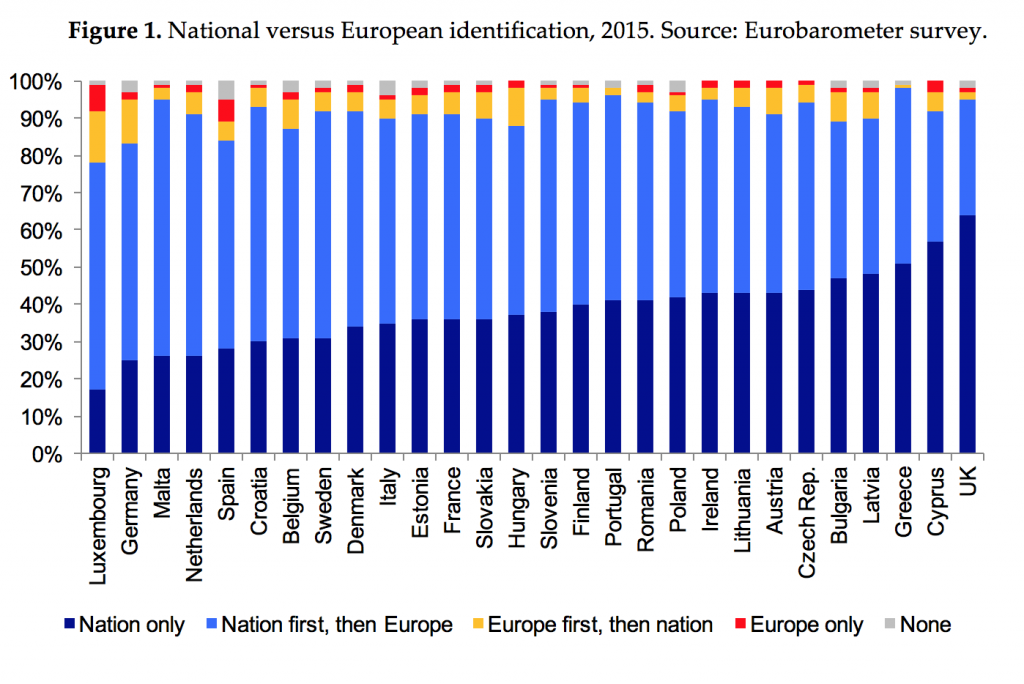

Figure 1 shows national versus European identification for all 28 EU member states. The UK is ranked 28 out of 28 for European identity: nearly two-thirds of Britons do not identify as European at all, compared to fewer than 40 per cent of French and Italians, and fewer than 30 per cent of Spanish and Germans.

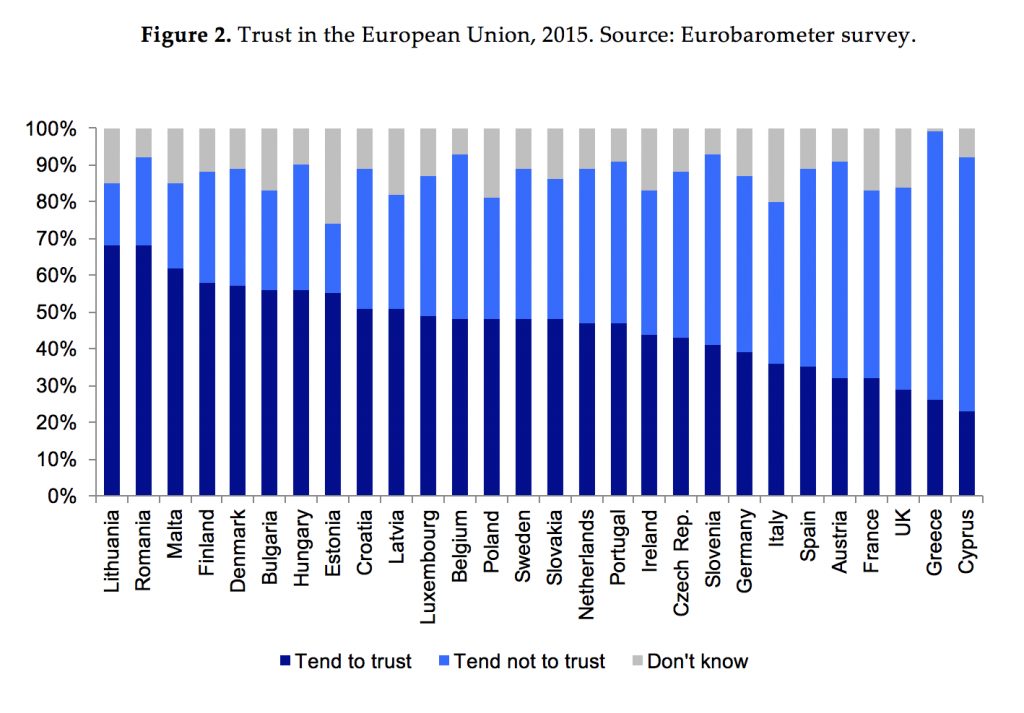

Figure 2 shows trust in the European Union for all 28 EU member states. The UK is ranked 26 out of 28: fewer than 30 per cent of Britons trust the EU, compared to 39 per cent of Germans, 47 per cent of Dutch and a full 57 per cent of Danes.

Figure 2 shows trust in the European Union for all 28 EU member states. The UK is ranked 26 out of 28: fewer than 30 per cent of Britons trust the EU, compared to 39 per cent of Germans, 47 per cent of Dutch and a full 57 per cent of Danes.

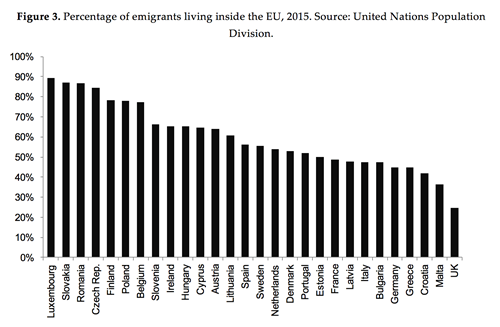

Figure 3 shows percentage of emigrants living inside the EU. The UK is ranked 28 out of 28, and by a non-trivial margin. Indeed, according to the latest UN data, there are more Britons living in Australia than there are in all 27 other EU countries combined.

Figure 3 shows percentage of emigrants living inside the EU. The UK is ranked 28 out of 28, and by a non-trivial margin. Indeed, according to the latest UN data, there are more Britons living in Australia than there are in all 27 other EU countries combined.

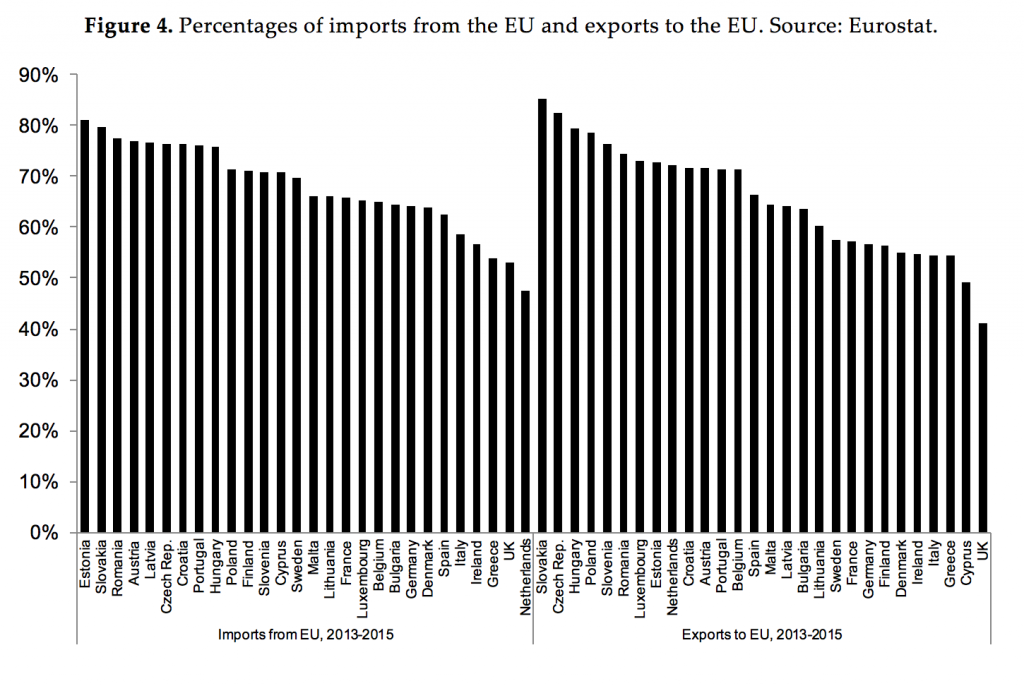

Figure 4 shows percentages of imports from the EU and exports to the EU. The UK is ranked 27 out of 28 for imports, and 28 out of 28 for exports.

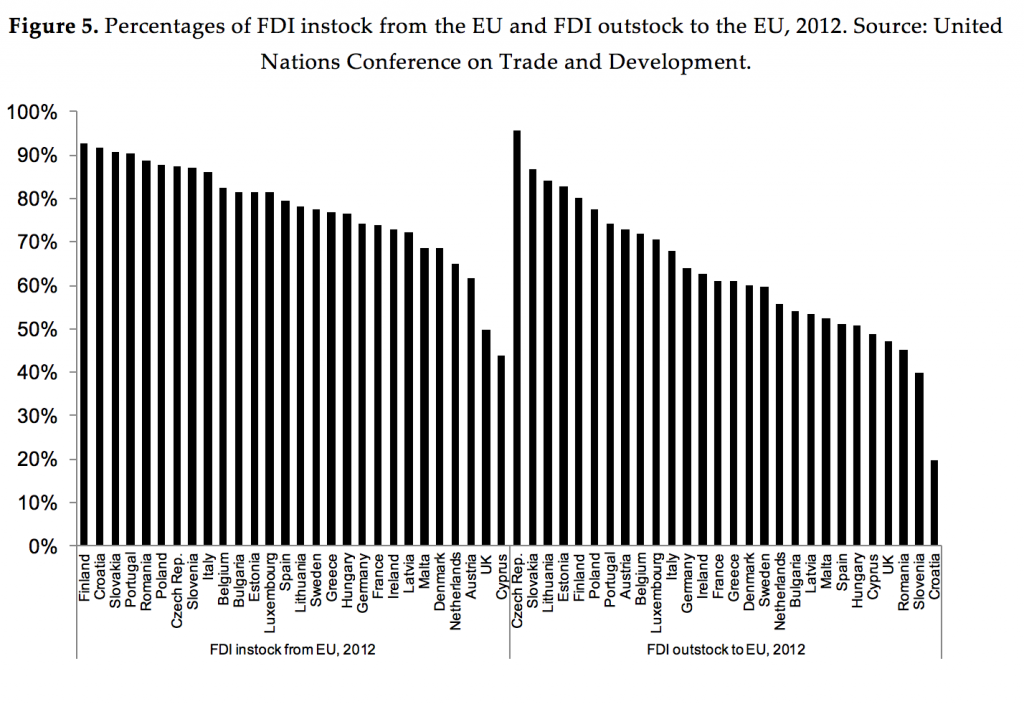

Finally, Figure 5 shows percentages of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) instock from the EU and FDI outstock to the EU. The UK is ranked 27 out of 28 on FDI instock, and is ranked 25 out of 28 on FDI outstock.

As the above charts illustrate, the UK’s comparatively limited integration into the EU is manifested in citizens’ self-identity, in their mistrust of the EU, in patterns of emigration, in international trade flows, and in foreign investment allocations. While the UK is not the lowest-ranked country on every single measure, it consistently ranks among the bottom two or three; the only countries that come close are Greece and Cyprus – both of which have suffered financial crises in recent years.

Britons’ comparatively less European self-identity and lower trust in the EU may have come about for the following reasons. First, Britain is the only allied European power not to have been occupied during the Second World War. Second, Britain has its own common law legal system, which contrasts with the civil law system of continental Europe. Third, because Britain has an established church, most British Christians have historically owed their allegiance to a national institution headed by the monarch, rather than to an international institution headed by the Pope. Fourth, Britain is an island whose surrounding waters have partially isolated it from cultural developments on the continent.

The fact that Britain’ does relatively more of its trade and investment outside of the EU, is due at least partly to the size and economic development of its former empire, the status of English as the global business language, and its particularly close ties with the United States.

All of these factors have served to stymie over-enthusiastically pro-EU business policy, exemplified most clearly in the previous Labour government’s decision to not join the Euro. In addition, Britain’s colonial past surely explains why relatively fewer of its emigrants choose to resettle in the EU. Indeed, several former British territories today have large British-descended populations

In conclusion, Britain is the least well-integrated EU member state: European, just not European enough. While short-term contingencies and concerns about other issues may have tipped the balance toward Leave, as the EU moved closer toward political union, the UK’s fundamentally less European character meant that Brexit was increasingly likely.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. It originally appeared on the LSE British Politics and Policy blog. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

James Dennison is a Researcher at the European University Institute in Florence. His work focuses on political participation. He is the author of The Greens in British Politics and tweets @JamesRDennison.

James Dennison is a Researcher at the European University Institute in Florence. His work focuses on political participation. He is the author of The Greens in British Politics and tweets @JamesRDennison.

Noah Carl is a doctoral candidate in the Sociology department at the University of Oxford. His research focuses on the correlates of beliefs and attitudes and he is an editor and contributor at the demography blog OpenPop.

Noah Carl is a doctoral candidate in the Sociology department at the University of Oxford. His research focuses on the correlates of beliefs and attitudes and he is an editor and contributor at the demography blog OpenPop.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

The ultimate causes of Brexit.

https://t.co/gLc2OIs9pf

“Leave may actually have had the lead throughout the entire campaign”

https://t.co/1gbAYd1O1p

#Brexit #EUref

[…] more interesting stuff here. Posted by John Souter in Libertarianism, LINX, Politics Comments: (0) Trackbacks: (0) […]

The ultimate causes of Brexit: history, culture, and geography https://t.co/7hSKX7rLf2

The ultimate causes of Brexit: history, culture, and geography https://t.co/Y39OPIbkmb

The ultimate causes of Brexit: history, culture, and geography https://t.co/JyoHttP5uz

Good stats in this article: The ultimate causes of #Brexit: history, culture, and geography https://t.co/XaPwi84K0I

The ultimate causes of Brexit: history, culture, and geography https://t.co/hqu9sViGEt https://t.co/68f1XoutFH