Now Indonesia has a sovereign wealth fund – and it won’t be the last

Little noticed by the wider world, Indonesia’s government recently announced details of the creation of one of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the region. Juergen Braunstein and Arianne Caoili argue the coming years will see a new wave of sovereign wealth funds, especially in countries with large state-owned enterprises.

The Fountain of Wealth, SunTec City, Singapore. Photo: William Cho via a CC-BY-SA 2.0 licence

Key players in international finance

Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are large state owned investment funds. With assets under management of about US $7trillion globally, SWFs have become key players in international finance – even surpassing the combined size of global hedge funds and private equity firms.

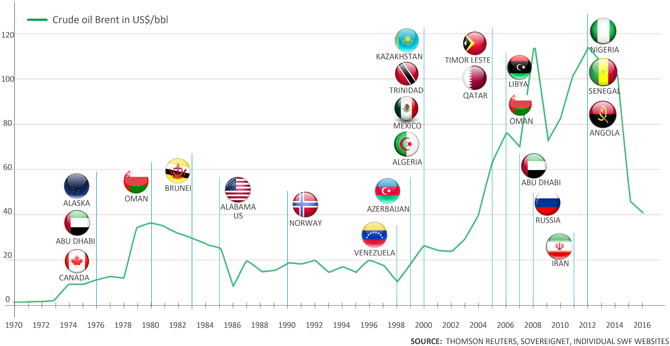

In the vast majority of cases SWFs were funded by the proceeds of oil and gas exports, and resource rich countries have particularly tended to create SWFs in periods when oil prices are high.

Oil price and the creation of carbon sovereign wealth funds

SWFs have traditionally been established to address a number of macroeconomic issues; for example, smoothening fiscal revenues, mitigating the ‘Dutch disease’ or saving for future generations. Reflecting these mandates, SWFs have tended to invest into foreign assets. However, over the next few years we expect to see the proliferation of a ‘new wave’ of SWFs with different characteristics, especially with regard to their funding structure and a movement towards domestic investments.

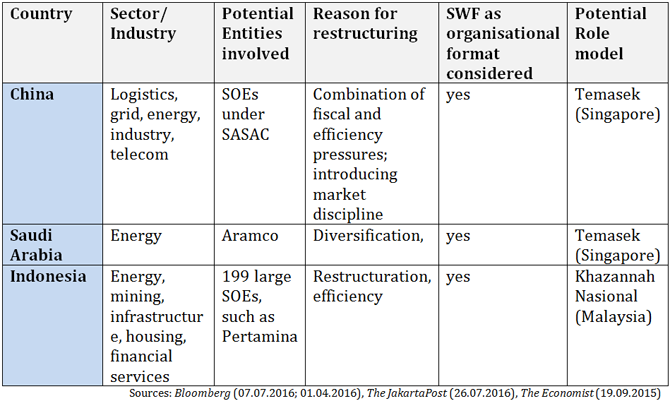

More and more SWFs are no longer being funded by the proceeds of energy exports. The funding differences in this ‘new wave’ are also reflected in their different objectives. The ‘new wave’ of SWFs is not so much about securing future rents, rather they are now used as mechanisms for fundraising or public sector restructuring. A significant part of the future SWF wealth is coming from the proceeds of large scale state owned enterprise (SOE) restructuring. China alone wants to restructure its US $16 trillion SOE sector over the coming years.

As vehicles to control SOEs, SWFs allow states to stay in control of firms while introducing market forces. This raises two questions. How does this operate in practice? And to what extent is this relevant globally?

Indonesia’s new $300bn sovereign wealth fund

Indonesia’s new SWF will be modelled after Malaysia’s Khazannah Nasional and will reportedly control US $320bn worth of assets by 2019. To accelerate the process, the government plans to create four sector-specific sub-holdings, starting with the energy sector.

The new SWF will replace Indonesia’s SOE Ministry and act as the parent for 199 of the largest SOEs. The restructuring of Indonesia’s SOE sector aims to decrease the SOEs’ dependence on the government budget. The SWF can then raise money on behalf of its companies via the market via a bond issue. While improving the fiscal situation, this should also increase efficiency and eliminate redundancies through better coordination among SOEs.

Indonesia is following in Singapore’s earlier footsteps. In the early 1970s Singapore’s government transferred the stakes of the Ministry of Finance Incorporation into Temasek – Singapore’s SWF created in 1974. Other ministries in Singapore followed promptly by transferring their assets into large sector specific-holdings, such as the Sheng-Li Holding (defence-related industries) and the Ministry of National Development Holding (housing development and land corporations). By the early 1980s most of the assets were merged into Temasek’s portfolio.

A new wave of sovereign wealth funds, just ahead?

Looking ahead, public sector reforms will provide strong tailwind for the creation of non-carbon funded SWFs. A number of countries, such as Kazakhstan and China, have expressed an intention to consider Singapore’s earlier state enterprise reforms that led to the creation of Temasek. Indeed, in an age of increasing budget deficits and the need to reform large SOE sectors, other potential candidates for SWFs might also follow suit.

Economies that have indicated plans to restructure SOEs

Past drivers and future directions

Against the backdrop of a commodity boom in the early 2000s carbon-funded SWFs experienced dynamic growth in number as well as size. However, since 2015 the momentum of growth in the number of carbon-funded SWFs has sharply dropped from its peak in 2012. In addition, public deficits have increased in many of the oil producing countries, which further narrows the potential for future carbon funded SWF growth.

In contrast, it is very likely that we will see the emergence of more non-carbon funded SWFs, particularly in Asia over the next few years. With countries determined to reduce the budget dependence of SOEs, while at the same time retaining strategic control, SWFs look like the perfect tool to tackle the challenges of the current economic climate.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit. It first appeared at LSE Government.

Dr Juergen Braunstein is a Senior Associate with LSE Enterprise and an affiliate with SovereigNet at the Fletcher School (Boston). Currently he is working with LSE and the New Climate Economy on a project on financing green infrastructure in urban spaces. He was awarded his PhD in Public Policy and Administration at the LSE Department of Government in 2016.

Dr Juergen Braunstein is a Senior Associate with LSE Enterprise and an affiliate with SovereigNet at the Fletcher School (Boston). Currently he is working with LSE and the New Climate Economy on a project on financing green infrastructure in urban spaces. He was awarded his PhD in Public Policy and Administration at the LSE Department of Government in 2016.

Arianne Caoili is an entrepreneur, international chess master, founder and chief editor of Armenia’s largest newspaper, Champord, and Managing Partner of Akron Consulting.

Arianne Caoili is an entrepreneur, international chess master, founder and chief editor of Armenia’s largest newspaper, Champord, and Managing Partner of Akron Consulting.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] This post appeared first at LSE Government and then at Democratic Audit UK. […]

Now Indonesia has a sovereign wealth fund – and it won’t be the #wealth #makemoneyonline https://t.co/qLAONRtHhV https://t.co/NAJ8Zn3y7t

‘We will see the emergence of more non-carbon funded SWFs, particularly in Asia, over the next few years.’ https://t.co/Yj3pLuwDtC

Now Indonesia has a sovereign wealth fund – and it won’t be the last https://t.co/75Ix989vlp

Now Indonesia has a sovereign wealth fund – and it won’t be the last https://t.co/Yj3pLuwDtC

Now Indonesia has a sovereign wealth fund – and it won’t be the last https://t.co/Yj3pLuf252 https://t.co/NNYuY07OnN