Without liberalism, democracy is dreadful. Fortunately we have both

It is quite all right to hate democracy. T. F. Rhoden dislikes democracy immensely. Without classical liberalism, he argues, it is normal to mistrust democracy in its purer form. Democracy is dreadful without the classifier “liberal” in front – because liberalism is a safeguard against democracy’s inherent decadence of rule by the people.

A Trump supporter holds a placard at a rally in Arizona, June 2016. Photo: Gage Skidmore via a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence

Whatever one thinks of Donald Trump’s election and Brexit, we might do well to pause briefly and consider the state of democracy as a regime type. Both elections make useful pedagogical tools. They toss into relief inherent aspects of this regime type – aspects that may appear hidden most of the time for many of us who fret over the condition of such things.

More than anything else, they should serve as a reminder that Britain and the United States are not pure democracies, but rather liberal democracies.

Democracy as demagoguery

As long as no monarch, no military junta, no unelected revolutionary vanguard or commission impedes this process of the people in their governing body, then democracy can be said to be working well. The people – the demos – vote on some course of action, as in the EU referendum, or they vote on some individual to lead a slew of actions in the US example. For those who win at this process, then there is much at which to rejoice. For those who lose, there is even more to dread. Indeed, without some form of institutional brakes and constitutional liberties, very little can stop a demos from putting into power a “tyranny of the majority.”

Democracy in its purest forms captures the joys of a winning majority as much as it does the fears of a losing minority. The ancient Greeks knew this well. So too did many of the founders of American government. Democracy as a regime type is nothing other than a vehicle for the demagogue. A well working democracy is, in fact, demagoguery pure and simple.

One of the more humorous misadventures in the scholarly literature on political transitology and democratisation is how comparative political scientists have thought that they need to “depict a ‘new species’, a type of existing democracies that has yet to be theorised” whenever they encounter a democracy that appears wanton. When we think of democracy in this more fundamental and classical sense, democracy naturally appears less appealing to the contemporary thinker. Is it any wonder that for many of the people living under one of these truer forms of democracy, governmental rule may seem more capricious and less predictable? “Democratisation” takes on a more sobering, even sinister, meaning for those citizens who have lost at the ballot box.

Some theorists have gone out of their way to describe this uglier aspect of democracy and call it a “delegative democracy.” Yet if we could only remember that democracy always has this harsher aspect within it, one could leave out the moniker “delegative” altogether. Unchecked, unbalanced incompetence voted into power: this is democracy without liberalism.

Liberalism before democracy

Democracy, when denuded and reaffirmed as “rule by the people”, does not in any way include – conceptually – the following: executive rule of law or constraints, judicial independence or review, civil liberty, property rights, religious freedom, media independence, or minority rights. All of these things, which are perceived as “inalienable rights” and taken for granted in liberal democracies, are in no way a fundamental aspect of democratic rule itself. They are a modern (and arguably tension-laden) addition to democracy.

These aspects, instead, form the core of liberalism.

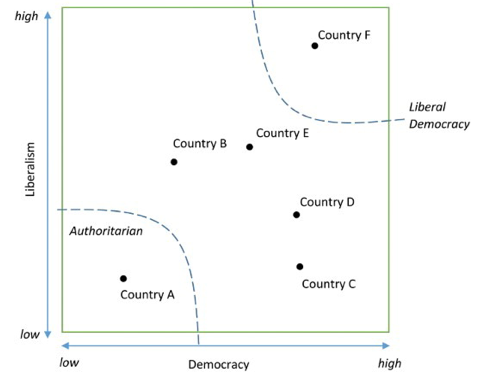

In one sense all contemporary national states have both democratic components and a liberal components, for we know of no purely democratic or purely liberal regime in the modern world. In the figure below, those national states that populate the top right of the graph (Country F) would normally be called liberal democracies, while the ones that are normally considered authoritarian would tarry about the bottom left (Country A). All the rest have been those sorry recipients of hundreds of different qualifying adjectives, each visualising itself as a new species deserving a new theorising.

Figure 1

Liberal democracy’s true form

A liberal democracy is more than the sum of its two parts. Some aspects of liberalism and democracy seem to fit together perfectly, while others nearly always seem in conflict with each other.

Those aspects that reinforce both would be something like the right to vote; as suffrage continued to expand over the centuries in the West, it made sense to say that liberalism was strengthened as larger segments of the population were afforded equal rights under the law – the right to vote in this case – at the same time as it made sense to say that democracy was strengthened when the vote was not only representative of one stratum of property-owning society, one race or ethnicity, one gender, and so on.

But for every instance in which liberalism and democracy seem to fit together, there are two or three additional aspects where – on good days – some trade-off or moderation is necessary, and where on bad days tension or conflict between liberalism and democracy are the norm. These are too numerous to catalogue here; but just one class of tensions is anything enshrined by constitution as a “right”, which at any one time or another may fall victim to the ire of a majority of the democratic population.

Some might argue that nearly every domestic political squabble within a liberal democracy is borne by the addition of liberalism to democracy. Some might argue that this is a furnace of dynamism. Both are correct.

State of liberal democracy

Let us ask again: what is the state of democracy in the world’s two – and arguably most important – liberal democracies, the US and UK?

Trump’s election and the referendum vote have illustrated that democracy, as in “rule by the people”, is functioning as well as it should be. A new executive will take office next year in the US and the traditional UK parliament, now (probably) freed from implementing rules and regulations from an extraterritorial source, will be a political body ever more receptive to the will of the majority at home. The democratic side of liberal democracy is doing just fine.

What those who lost at the ballot box need to remember is that they already have a constitutional check on this “tyranny of the majority” in the form of liberalism. Just as those on the farther Right have deployed constitutionalism in the past to block the excesses of the farther Left, it is now the turn of the farther Left to draw upon those same tools of liberalism. And when has it never not been this way during the past few centuries in these two liberal democracies?

The test of the liberal side of liberal democracy will come in the next months and years. Surely the liberalism of our liberal democracies is more than strong enough to fend off the ever-present overindulgence of demagoguery? The farther Left needs to remember that the more it whines about their recent losses, the more hope there is for our state of – not democracy – but our state of liberal democracy. For it is only when politics and politicking reach an ever higher pitch of contestation that liberal democracy will shows its worth as a regime type.

For those who think we live in strange or sordid times, I would say that if the regime under which we lived were only a democracy unadorned, I might agree with you. Critically, we do not live under any tawdry form of people’s despotism.

With an honest tenaciousness that I hope strikes at the heart of the milksop political scientist and political pundit in equal measure, it is because I embrace the liberalism in liberal democracy that I understand that we live in very exciting times. Indeed, there has never been a greater time to be alive in the history of these two great liberal democracies.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It is based on an article in Democratization, The Liberal in Liberal Democracy, which is free to access for readers of this post.

T. F. Rhoden is a PhD Candidate at Northern Illinois University.

T. F. Rhoden is a PhD Candidate at Northern Illinois University.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] This article was originally published at Democratic Audit UK and it gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and […]

This surely is the point and indeed why these are exciting times – in the UK for example it was felt by much of the elite that vast numbers of rules and laws could be enshrined forever via that unelected ‘extraterrestrial’ source the EU, and that therefore (‘cards on the table’) representative democracy was really no longer needed other than as a pretend figleaf: that has been given a major jolt by the June vote.

Supranational bodies will still have a major role – in the UK we will just be getting rid of the no-longer-necessary middle man for many international rules and laws – but that process in itself gives greater edge to democracy, and means that there WILL be more choice.

Sobbing bitter tears in their tents will not be enough for those with a view that differs – those with a different view (say of Brexit) will now have to go out and work as hard as those on the other side have been doing for two decades. Capturing hearts and minds face-to-face with passion and conviction is how you have to do it, not patronising the voter from a tv studio or with a load of celebs saying how cool you are and how evil the other side is.