Faith schools do better chiefly because of their pupils’ backgrounds

Faith schools generally achieve better exam results than their counterparts, with Roman Catholic schools doing particularly well. If government proposals go ahead, oversubscribed new faith schools will soon be allowed to select all their pupils according to religion, rather than only half of them. But how much of their success is down to their intake? Rebecca Johnes and Jon Andrews find that much of the difference can be attributed to pupil characteristics such as eligibility for free school meals.

Photo: Mafleen via a CC-BY-NC SA 2.0 licence

In a recent green paper, Schools that work for everyone, the government set out a series of proposals to increase the number of good school places available in England. Among these is a proposal to remove the 50 per cent cap on faith-based admissions for oversubscribed faith free schools, arguing that this measure has not in practice achieved its intended aim of promoting inclusion and cohesion. By removing the cap, the government hopes that faith groups will be encouraged to open new free schools and increase the supply of good school places, under the assumption that such schools will provide a good quality of education.

Last week, the Education Policy Institute published a report which examines the characteristics of pupils who attend existing faith schools, the extent to which faith schools are socially selective, and the attainment of pupils who attend them. (For our purposes, a faith school is one with a designated religious character recorded on Edubase.)

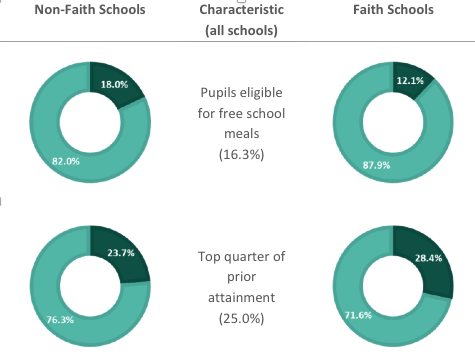

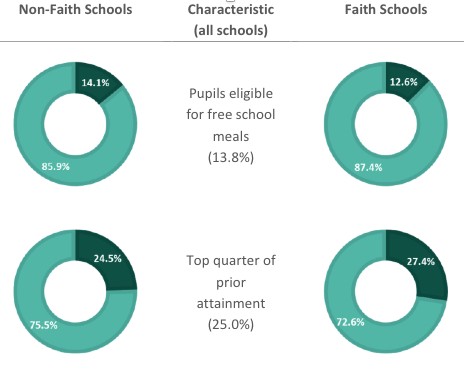

Pupil characteristics

We found, firstly, that the demographic profile of pupils at faith schools differs from that of pupils at non-faith schools. In particular, disadvantaged pupils are under-represented at faith schools, while those with high prior attainment are over-represented. The percentage of faith school pupils eligible for free school meals (FSM, a proxy for disadvantage) is below both the national average and the figure for non-faith schools; this is the case across faith schools as a whole and for almost all religious categories. The difference is particularly stark at primary level. Conversely, the proportion of pupils in the top 25 per cent nationally for prior attainment is above 25 per cent across faith schools as a single group and in each faith group analysed.

Figure 1: Pupil characteristics at Key Stage 2, by religious character of school. Derived from analysis of the National Pupil Database, 2015. The darker shading refers to the characteristic being described (e.g. 18.0 per cent of pupils in non-faith schools are eligible for free school meals).

Figure 2: Pupil characteristics at KS4, by religious character of school. Derived from analysis of the National Pupil Database, 2015. The darker shading refers to the characteristic being described (e.g. 14.1 per cent of pupils in non-faith schools are eligible for free school meals).

Social selection

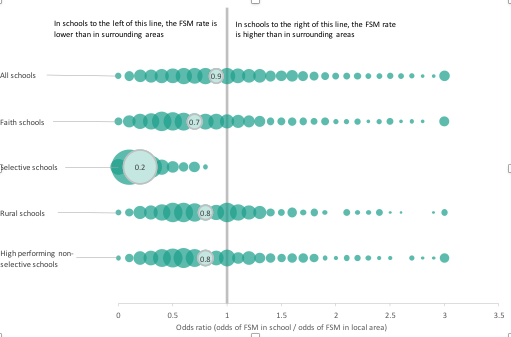

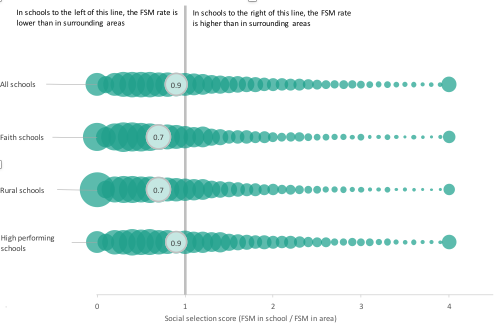

Beyond comparisons with national averages, the report also measured how representative different schools are of their local communities. A ‘social selection score’ was calculated for each school, comparing the proportion of pupils eligible for FSM in the school with the proportion of FSM pupils in the local area. (This score is known as an odds-ratio: the odds of a pupil in the school being eligible for free school meals divided by the odds of a pupil living in the local area being so. A score of 1.0 means that these two proportions are aligned; a score below 1.0 means that FSM pupils are under-represented in the school; and a score greater than 1.0 means that FSM pupils are over-represented in the school.)

At secondary level, faith schools had a median social selection score of 0.7, meaning that at the average faith secondary school, the odds of a child being eligible for free school meals are around two-thirds of those for all children living in the local area. In addition, although there are a number of secondary faith schools in which FSM pupils are over-represented, nearly 1 in 10 faith schools are at least as socially selective as the average grammar school (median score 0.2); this compares with around 1 in 30 non-faith, non-selective schools. Primary faith schools likewise had a median social selection score of 0.7.

Figure 3: Extent to which different types of secondary schools are representative of their local area. Size of bubble is proportional to the proportion of schools having that score. Median for each group is highlighted. Scores are capped at 3.0 for secondary schools; these scores should therefore be interpreted as 3.0+.

Figure 4: Extent to which different types of primary schools are representative of their local area. Size of bubble is proportional to the proportion of schools having that score. Median for each group is highlighted. Scores are capped at 4.0 for primary schools; these scores should therefore be interpreted as 4.0+.

Pupil attainment

In terms of raw attainment, the report found that faith schools do achieve higher results than non-faith schools at both Key Stage 2 and Key Stage 4. Across all categories of faith school examined, the proportion of pupils achieving Level 4 or above in reading, writing and maths at Key Stage 2 was equal to or higher than the equivalent figure for non-faith schools, with 83 per cent of pupils in Church of England schools and 85 per cent in Roman Catholic schools reaching this benchmark, compared with 81 per cent in non-faith schools. Overall, with respect to raw attainment (measured by average point score at Key Stage 2), primary school pupils in faith schools make around half a term’s more progress than those in non-faith schools. Likewise, at secondary level, the proportion of pupils achieving 5+ GCSEs at grades A*-C including English and maths was higher in most categories of faith school than in non-faith schools: 60.6 per cent at Church of England schools, 63.2 per cent at Roman Catholic schools, and 57.4 per cent at non-faith schools. For faith schools as a whole, the difference in raw attainment (measured by capped GCSE and equivalent point score) amounts to pupils achieving nearly one-third of a grade higher in each of 8 GCSE subjects compared with non-faith school pupils.

However, much of these differences are explained by the characteristics of pupils who attend faith schools. The analysis went on to control for pupil characteristics (including deprivation, ethnicity, and prior attainment), by identifying a control group of pupils attending non-faith schools with similar characteristics to those at faith schools. At Key Stage 2, the difference in attainment between faith and non-faith schools is largely eliminated once pupil characteristics are accounted for in this way. At Key Stage 4, the premium associated with faith school attendance remains but is much reduced, falling from nearly one-third of a grade in each of 8 GCSE subjects to just over one-seventh of a grade in each of 8 GCSE subjects; this is a relatively small attainment gain.

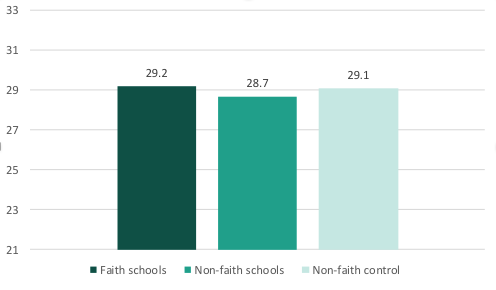

Figure 5: The attainment (average point score) of pupils in faith schools, pupils in non-faith schools, and a group of pupils in non-faith schools matched to similar pupils in faith schools at the end of KS2. Note that due to the relatively small number of pupils in non-Christian faith schools, and their different characteristics, this analysis is restricted to those that attend Church of England, Catholic and Other Christian faith schools. Analysis is restricted to those pupils with both current and prior attainment.

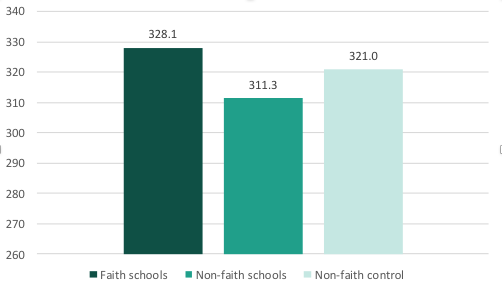

Figure 6: The attainment (capped GCSE and equivalent point score) of pupils in faith schools, pupils in non-faith schools, and a group of pupils in non-faith schools matched to similar pupils in faith schools at the end of KS4. Note that due to the relatively small number of pupils in non-Christian faith schools, and their different characteristics, this analysis is restricted to those that attend Church of England, Catholic and Other Christian faith schools. Analysis is restricted to those pupils with both current and prior attainment.

While encouraging more faith schools to open may help the government to meet its requirement to provide sufficient school places, the proposed policy is unlikely to yield places that are of a substantially higher quality than that offered by non-faith schools. Furthermore, given that faith schools on average admit fewer pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds than non-faith schools, there is a risk that these small gains would come at the price of increased social segregation.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit.

Rebecca Johnes is Research Officer in Education at the Education Policy Institute.

Rebecca Johnes is Research Officer in Education at the Education Policy Institute.

Jon Andrews is Director of Education Data and Statistics at the Education Policy Institute.

Jon Andrews is Director of Education Data and Statistics at the Education Policy Institute.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] Note: This post was originally published on Democratic Audit. […]