When Americans believe in redistribution and the right to a job, they’re more likely to vote Democrat

The concept of democracy often means different things to different people. But are there elements on which people can agree or disagree? Judd R. Thornton and Kris Dunn examine the relationship between US citizens’ beliefs about democracy and how they vote. They find that while most people believe that free elections and protecting civil rights are essential to democracy, Democrats are more likely to believe that redistribution and unemployment security are essential parts of democracy, while Republicans are not.

Wastin’ time in the unemployment lines… Tracy Chapman, a Democrat supporter, at TED 2007. Photo: advencap via a CC-BY-SA 2.0 licence

Democracy is a concept that can be defined in a whole host of ways. It therefore seems only natural that citizens do not always agree on what is (or is not) required for a country to be a democracy. This leads to two questions: are there areas of agreement and disagreement about what characteristics are essential? And, are these beliefs related to who one chooses to vote for?

In new research, we examined a series of such characteristics among a sample of citizens in the United States. The data, from the World Values Survey, offers respondents a series of statements about democracy—for example, “civil rights protect people’s liberty against oppression”—which are then rated on a scale ranging from one (“not at all an essential characteristic of democracy”) to ten (“an essential characteristic of democracy”).

While the responses to these questions indicate there is no single overarching view of what democracy requires, there is a fairly widespread consensus around certain characteristics. For example, the vast majority of the respondents, about 85%, believe that free elections are essential to democracy (i.e., report a six or above). Likewise, more than 80% of respondents believe that protecting civil rights and women’s rights is essential for democracy.

On the other hand, there exists some characteristics that only a small handful of respondents believe are essential. In particular only about 10% believe that religious authorities should be in charge of interpreting the laws in a democracy, and about 25% believe that democracy requires the army to take over if the government proves to be incompetent. While variation in beliefs about democracy is to be expected, it is nevertheless reassuring to find that the vast majority in the United States reject characteristics that are most commonly associated with non-democratic regimes.

What we find to be most interesting are those characteristics that provoke substantial disagreement among the sample. We will focus on two of these. First, about 40% believe that democracy requires that the government uses taxes to redistribute wealth. And about half believe that democracy requires the state to protect people from unemployment. It is worth re-emphasising that these respondents are asked if they consider these characteristics to be essential to democracy. In other words, it is not merely if one supports redistribution- or unemployment-related policies, but whether one thinks the characteristic is necessary in a democratic society.

Given that certain characteristics are more associated with democracy in the minds of some people than they are in the minds of others, we reason that this may act as a source of policy disagreement among voters. Simply put, if you believe that democracy requires wealth redistribution and protection from unemployment, then it seems reasonable to expect you to support a party that appears to believe that same thing; in this case, we would expect the person to support the Democrats.

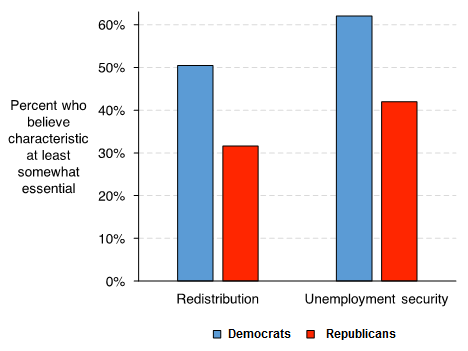

Accounting for various other considerations such as one’s age, education, income level, and sex, among other things, we find that certain beliefs about democracy do indeed correspond with one’s vote choice. Figure 1 displays the percentages of Republican voters and Democratic voters who view the characteristics as at least somewhat essential compared to those who do not for both issues. More than 60% of Democrats believe unemployment security is essential for democracy while about 60% of Republicans think it is not. Democrats are fairly even split on whether they believe redistribution is essential a democracy while Republicans are predominantly in the ‘not essential’ camp.

Fig 1: Beliefs about democracy by voter

It is worth emphasising that while there is clearly partisan divergence on whether one believes that these characteristics are essential for democracy, it is not the case that partisans in the electorate are irrevocably split. That is, we do not observe that Republicans uniformly believe that redistribution and unemployment security have nothing to do with democracy. Nor do we observe that Democrats uniformly believe that democracy does require such. Nevertheless, there does exist an important disagreement. Stronger positions on both of these characteristics increases the probability that one will vote for a Democratic candidate while weaker positions increase the probability of a Republican vote.

The take away message that we are proposing here is that policy preference may be at least partially rooted in people’s beliefs about what democratic governance requires. Does a democratic system of governance guarantee a certain standard of living or degree of economic equality? The widespread and cross-party belief that civil rights and women’s rights are essential for democracy indicates a near consensus regarding the necessity of political equality in a democracy. However, there is a potentially fundamental cross-party disagreement around whether democracy requires some degree of economic equality. If you believe that democratic governance requires the government to ensure at least some level of material security, you will possibly be at odds with those who believe that democracy does not require such, and you will certainly be at odds with those who believe democracy requires that the government not interfere with people’s material wellbeing at all.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Vote intent and beliefs about democracy in the United States’, in Party Politics. It was first published at LSE USAPP.

Judd R. Thornton is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at Georgia State University. His primary focus is on mass political behaviour. In particular, his interests include partisanship, beliefs systems and ideology, the interplay between elite and mass opinion, and issues of measurement.

Judd R. Thornton is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at Georgia State University. His primary focus is on mass political behaviour. In particular, his interests include partisanship, beliefs systems and ideology, the interplay between elite and mass opinion, and issues of measurement.

Kris Dunn is a Lecturer in Comparative Politics and Political Psychology in the School of Politics and International Studies at the University of Leeds. His research focuses on representation, ideology, culture, and authoritarianism and seeks to increase our understanding of how individual (pre)dispositions and social and political environments interact to influence individual political attitudes, behaviours, beliefs, and identities.

Kris Dunn is a Lecturer in Comparative Politics and Political Psychology in the School of Politics and International Studies at the University of Leeds. His research focuses on representation, ideology, culture, and authoritarianism and seeks to increase our understanding of how individual (pre)dispositions and social and political environments interact to influence individual political attitudes, behaviours, beliefs, and identities.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.