Another Lords review bites the dust. What will it take to reform the second chamber?

The long saga of abortive Lords reforms goes on. Theresa May has added a new chapter by backing off from her predecessor’s plans to strip the second chamber of its power to vote down statutory instruments – the main form of delegated legislation, which are vital to the UK government’s extensive executive powers and to implementing Brexit. Richard Reid says this is a pragmatic decision that nonetheless continues a tradition of leaving the Lords’ functions and status in limbo.

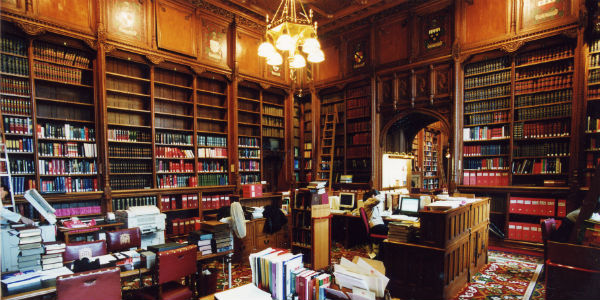

The Queen’s Room in the House of Lords Library. Photo published under parliamentary copyright

The May government has decided not to pursue the Strathclyde plan to reduce the powers of the House of Lords, to which David Cameron had committed himself as PM. This is an unsurprising development, joining a litany of failed attempts at Lords ‘reform’.

The background to the latest proposal will be familiar. In 2015, the House of Lords refused to give their agreement to a statutory instrument that would have cut tax credit payments to hundreds of thousands of people – contained in the Tax Credits (Income Thresholds and Determination of Rates) (Amendment) Regulations 2015. The Cameron government subsequently dropped their proposal, and indeed George Osborne went on to make political capital from the shift. Understandably, however, the government was frustrated at being initially blocked by the Lords. But rather than admitting that the proposals were unpopular, appeared to resile on Tory campaign pledges in 2015, and that the legislative means for securing them was ill-planned, the government responded with a review into the powers of the Lords over secondary legislation.

Lord Strathclyde, the former long-serving leader of the Tory peers and former Leader of the House of Lords, was commissioned to lead an expert panel to review the powers of the second chamber. The Strathclyde Review reported in December 2015, outlining three options: (1) the retraction of Lords powers over statutory instrument procedure in its entirety, (2) the maintenance and codification of the status quo, and (3) a legislatively-defined new procedure in which statutory instruments would be treated like most legislation, whereby the Lords would lose their veto but would be able to suggest amendments to the Commons, who would have the final say. The Review recommended option three.

On 17 November Baroness Evans of Bowes Park, the Leader of the House of Lords appointed by Theresa May, announced that the government would not curb the powers of the Lords:

The Government agree with my noble friend Lord Strathclyde’s conclusion that on statutory instruments, as with primary legislation, the will of the elected House should prevail, and we believe that his option 3 provides a credible means of achieving this. However we do not believe that we need to introduce primary legislation at this time. We recognise the valuable role of the House of Lords in scrutinising SIs, but there is no mechanism for the will of the elected House to prevail when they are considered, as is the case for primary legislation. The Government are therefore reliant on the discipline and self-regulation that this House imposes upon itself.

She then went on to make what must be considered an empty threat: ‘[s]hould that break down, we would have to reflect on this decision’.

In the official government response to the Review, published on 1 December, David Lidington, the Leader of the House of Commons, echoed the remarks made by Baroness Evans:

Whilst recognising the valuable role of the House of Lords in scrutinising Sis [statutory instruments], the Government remains concerned that there is no mechanism for the elected chamber to overturn a decision by the unelected chamber on SIs. We do not believe that it is something that can remain unchanged if the House of Lords seeks to vote against SIs approved by the House of Commons when there is no mechanism for the will of the elected House to prevail. We must, therefore, keep the situation under review and remain prepared to act if the primacy of the Commons is further threatened.

The government have thus given the impression that, despite refusing to undertake legislative intervention to curb the Lords powers, they remained dissatisfied with the existing arrangements.

The government’s decision to shelve the Strathclyde Review, while admitting their unhappiness with the current powers of the Lords, demonstrates the continuation of what has proved a prolonged and immobile debate, one initiated by Tony Blair’s failure to deliver his promised ‘stage two’ of Lords reform. Successive governments have been open in their distaste for the present structure and function of the Lords, yet have evidently lacked the political will to initiate and legislate for any serious reform.

The recommendations of the Strathclyde Review were not unproblematic. They were made in a climate of government petulance at having its will obstructed. So while Strathclyde suggested a reasonable reform, as has been argued elsewhere such an important change in the balance of power within parliament needed to be considered in a more wide-ranging, joint committee of the two houses.

What is disappointing about the government’s response is not that it failed to put into legislation the recommendation of the Strathclyde Review, but rather its decision to add more to the recent tradition of complaining about the Lords while doing nothing to pursue reform. The government climbdown obviously derives from a desire to avoid confrontation with the Lords, given the soon-to-be introduced legislation to facilitate Brexit. But it maintains the seemingly indefinite intra-governmental stalemate between deprecating the remaining powers of the all-appointed upper house and lacking the willpower to undertake reform. Perhaps a Lords revolt over Brexit might prove the encouragement the government needs to address this constitutional conundrum.

The debate regarding reform often clouds the true function of the second chamber – legislative scrutiny – and it proves too tempting for governments to cry foul when they don’t get their way. In the flow of immediate political convenience, governments seem unwilling to appreciate that they have a serious duty to end the uncertainty which has long surrounded the powers and composition of the Lords.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It first appeared at LSE British Politics and Policy.

Richard Reid is a researcher at the Australian National University. In 2016 he completed his thesis on House of Lords reform, and continues to research its procedure, functions, and future. He has published a recent article on the role of ideas in reform. He would like to thank Patrick Dunleavy and Lachlan Jones for their helpful comments on earlier versions.

Richard Reid is a researcher at the Australian National University. In 2016 he completed his thesis on House of Lords reform, and continues to research its procedure, functions, and future. He has published a recent article on the role of ideas in reform. He would like to thank Patrick Dunleavy and Lachlan Jones for their helpful comments on earlier versions.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Changing the rules re Lords treatment of Statutory Instruments would

not address the fundamental issues BUT would hamper proper scrutiny

of Executive actions AND divert attention from the pressing issue of the

size of the membership of the House.

At last (!) the House of Lords is about to develop its own proposals

for a reduction in its size. This would seem to accept the principle

of a cull but, as ever, the devil is in the detail.

Three principles need to be inform implementation of the cull.

a) Independence of cross-benchers and the Appointments

Commission must be maintained.

b) The government party/parties must have 50% of the

party-partisan membership with the other 50% being

available to all other parties according to their rated

proportion of votes at the last General Election.

c) No more than 50% of the allocation to each party should

be controlled by the party leadership – the majority of the

membership being decided by members of the party group.

I have prepared a paper with greater detail of the methodology

and a copy is being sent to Lord Burns whom I believe to be the

convenor of the group established by the Lord Speaker to look

into this matter..