If your parents didn’t vote, chances are you won’t either – unless you move up the social ladder

You are less likely to vote if your parents didn’t go to the polls. But new research by Hannu Lahtinen, Heikki Hiilamo and Hanna Wass suggest this effect is at least partly overcome if you move up the social ladder yourself. The more social mobility a society can achieve, the smaller the gaps in turnout between social classes.

At the electoral congress of the Polish People’s Party, October 2016. Photo: Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe. Public domain

Voter turnout is – increasingly – a class issue. In the 2010 British parliamentary elections, the difference in reported turnout between the working and middle classes was 19 percentage points, compared to less than just five percentage points in 1964. Nordic countries, too, have been characterised by a relatively clear class bias in electoral participation. Along with many other socio-economic measures, patterns of participation and non-participation are passed down from one generation to the next.

Voting is habitual: the first few elections are crucial in developing the habit. This means that differences in levels of political activity persist throughout an individual’s life. If a child never witnessed her parents going to the polls, she may well never do so either.

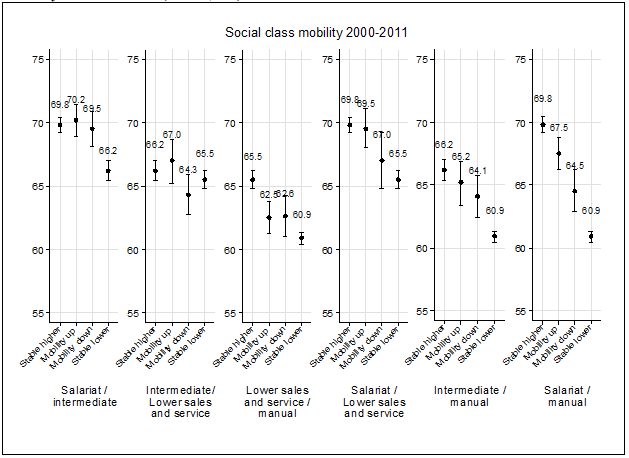

But our recent study suggests the picture might not be as gloomy as it seems. Intra-generational social and economic mobility seems to work to reduce the socio-economic bias in turnout. This effect is called “gradient constraint”, and was originally described in social epidemiology by Mel Bartley and Ian Plewis. Applied to electoral participation, the gradient-constraint hypothesis implies that turnout among upwardly-mobile individuals is higher than the non-mobile members of the class they came from – but still lower than the class where they end up. Among those whose class status has shifted downwards, the opposite applies.

Our results show that turnout among the mobile individuals settles between the averages of their original social class or income group and those among the class where they end up who did not experience social mobility during the period covered in our analysis. An individual’s current social class and income are linked to their voting habits in a way that cannot be fully attributed to education, past voting, parental voting or their previous social class or income. Instead, the results suggest that voters have a tendency to adjust their turnout patterns to match the standards of their new social standing. It is worth pointing out that they do not vote quite as often as the average of their new group. This seems only logical, given the importance of childhood and early adulthood in forming habits. Overall, however, when it comes to turnout, intra-generational social mobility does help to narrow socio-economic inequality.

Estimated turnout probability in the 2012 Finnish 2012 municipal elections (%) with 95 percent confidence intervals by social class pairs and mobility between them (n=143,322). Based on logistic regression adjusted for gender, age, education and voting in in 1999 parliamentary elections and parental voting in 1999.

In validating the gradient-constraint hypothesis, we used a unique dataset that links individual-level voting records from the 2012 Finnish municipal elections with information on socio-economic background characteristics compiled by Statistics Finland. On the bases of personal identification codes, voters’ social class and income in 2000 and 2011 were matched to voting in the 1999 Finnish parliamentary elections in the dataset. Using actual voting records means our data are not subject to the bias characteristic of self-reported turnout, such as misreporting due to faulty memory, or over-reporting due to social desirability.

Social class and income-related representational bias in parliamentary institutions is very important, since they are directly related to an individual’s position on policy issues like welfare benefits and tax rates. If the values and interests of non-voters differ from those of voters, citizens who cast their vote become better represented. Studies conducted in the US have shown that political decision-making favours wealthier citizens. Similar results were found in a cross-country comparison.

As intra-generational social mobility can go some way to neutralising voting inequalities, achieving an open society with a higher level of mobility may narrow the socioeconomic gradient in turnout. Policy makers could, for example, invest in adult education and in vocational training especially targeted at those with fewer qualifications and in less-skilled jobs. In addition, narrowing overall income inequality is likely to lead to more intra-generational income mobility, since the absolute “distance” between income groups becomes smaller and thus easier to overcome. With the gradient-constraint mechanism, this would reduce the gap in turnout between income groups.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit.

Hannu Lahtinen is a researcher at the Department of Social Research at the University of Helsinki.

Heikki Hiilamo is Professor of Social and Public Policy at the University of Helsinki.

Hanna Wass is an Academy Research Fellow and University Lecturer in the Department of Political and Economic Studies at the University of Helsinki. Her current project “Equality in electoral participation and vote choice”, funded by the Academy of Finland, examines turnout and representation from various perspectives.

Hanna Wass is an Academy Research Fellow and University Lecturer in the Department of Political and Economic Studies at the University of Helsinki. Her current project “Equality in electoral participation and vote choice”, funded by the Academy of Finland, examines turnout and representation from various perspectives.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

An additional point often made in the UK is that these figures may have altered (back to closer in % terms) since UKIP became a major player well AFTER that 2010 election.

One of the things often missed by people looking at elections and turnouts (and at those who can’t be bothered) is the simple question: “are the parties offering any reason for those NOT voting to turn out?”. Saturation daily coverage for three months and more of, say, the London Mayor election still only manages to achieve an abysmal turnout of one in 3. It’s not all to do with the need to dragoon the working classes into “behaving like their betters”. What was the difference for an average working class voter in 2010 between New Labour and the left of centre Tories? If you have grasped this, and feel that no other party will do well enough to get rid of the one-party state, then you think: why bother voting?

It does appear that UKIP in the UK has, since its major rise and victory in the 2014 European elections, harnessed to quite a degree the support of those (many working class) who couldn’t be bothered.

In the UK and with UKIP (and indeed the Greens who were the early contributors to this welcome debvelopment) this is positive and has no real downside. But look elsewhere and people are missing some very serious and worrying trends.

Recent stats provided by international research, like the Friedrich Ebert institute for example (and not only local opinion polling) show that Jobbik in Hungary and Golden Dawn in Greece are now clearly the ‘party of choice’ (the words of the researchers) for the youngest group of voters, hitting over 50% declared support in the former.

One tends to wonder whether those tut tutting about working class and youth non-involvement in electoral politics will be quite so keen to turn that upside down if it leads to massive rises in the numbers of elected members for parties like those!

[…] View Original: If your parents didn’t vote, chances are you won’t either – unless you move up the social ladd… […]