The ‘academy revolution’ is ousting governors. We need to hold these schools accountable

As more and more schools are removed from local authority control and become academies, the role of governors has diminished – and with it a school’s accountability to local people, argues Andy Allen. Contrary to the aim of the ‘school revolution’, multi-academy trusts are not autonomous at all, but answerable to a few unelected trustees. He calls for a new model in which local membership groups would elect forums to advise governing boards.

Sääksjärvi School Choir from Lempäälä in Finland, 2009. Finnish schools are frequently held up as a model for British education. Photo: 350.org via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence

How schools are governed is more important today than ever before. Why? The answer is that almost 5,000 state-funded schools have converted to academies. Astonishingly, this means that over 60% of all secondary schools in England are now privatised organisations, so the tipping point in the creation of an ‘independent’ state school system has been passed.

Although the government was forced – following a public and political outcry – to backtrack on its policy to ‘complete the school revolution’ by converting all schools to academies, schools have continued to convert at a steady rate.

Given that academies are independent, private companies answerable via an unelected school commissioner to the Secretary of State for Education, it is apparent that the traditional accountability of the school system – community-grounded and democratic – is disappearing. The academy sponsor E-ACT is a prime example. It made the controversial decision to, as the BBC put it, ‘scrap its governing bodies’. The move was described as ‘repugnant’ and ‘authoritarian’ by one governor and the National Union of Teachers said it was undemocratic and sets a dangerous precedent. It is hard to believe that government-academy funding agreements can vest power in a handful of trustees that have no obvious right to wield it.

Further eroding the democratic base of school governance, the government has sought to half the size of boards from a typical 16-20 members. It even announced this year that parents will have no entitlement to a place on the governing board, a plan that has since been reversed by the education secretary, Justine Greening.

Academy autonomy and accountability

The idea of the autonomous school is not new, and is arguably based upon the principle that there is little the public sector can do that the private ‘marketised’ sector cannot do better. This ideological perspective was applied to education by both Conservative and Labour administrations, resulting in Grant Maintained Schools, City Technology Colleges and the City Academies. During the early period of academisation, sponsors from the private sector were invited to run the academies as efficient ‘edu-businesses’. However, few sponsors materialised because of the requirement to contribute financially so this requirement was removed. But the legacy term ‘sponsor’ stubbornly remains and should realistically be replaced by a more accurate term.

A useful rationale for the coalition government’s drive for autonomous academies was provided by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) rankings. Finland, with its pedagogical and administrative freedoms, was at the top of the table. The OECD argued that its list was much more than a ranking, and that it was effectively a tool to assist government policy. The indication was that when autonomy and accountability were intelligently combined they tended to be associated with better school performance. Hence the coalition government used this argument to convert state-funded schools into academies at an unfettered rate.

Yet an academy within a multi-academy trust is not autonomous at all; its accountability route has simply been re-directed from the local authority to the trustees of the ‘privatised’ sponsoring trust.

The democratic deficit

A growing number of academics and practitioners refer to the ‘democratic deficit’ within the governance arrangements of academies, because control is placed outside established public accountability systems. The Academies Enterprise Trust, the largest multi-academy trust in operation, is an interesting example. The trust in question operates scores of academies up and down the country and, until recently, had a board comprising of only four (unelected) trustees. Surprisingly, the DfE line on governance arrangements is that Trusts are best able to decide the format that suits their needs, even though such small groups of unelected individuals are potentially responsible for large sums of public money – upwards of £250m.

Following a ‘Financial Notice to Improve’ from the DfE, this trust has sought to strengthen its board. However, appointments in such cases may often be made by recommendation and nomination and it is unlikely that the broader community will be involved within the process – or receive a place at the exclusive non-executive table.

A 2014 study by Andrew Wilkins is critical of small governing boards and suggests that many schools are increasingly governed by unelected cliques, leading to an accountability deficit and regulatory gap which allow poor governance to go undetected. Similarly, a handbook published by the Institute of Chartered Secretaries noted that ‘the first port of call for academies looking for governors is the connections of those already on the board’.

Governance failings continue, and have over the last few years numerous accounts of fraud and financial irregularities have emerged. Nigel Gann’s paper, Education ethics: the probity of school governance makes this point, and his views are supported by a number of commentators, not least Greany and Scott’s report for the Education Select Committee (ESC). It advised

‘Conflicts of interest are common in academy trusts and that this is not surprising given the design of academies as independent autonomous organisations spending public money’.

Indeed, there is an ongoing ESC inquiry into multi academy trusts, of which governance is a central theme. This stems from a range of concerns, and from an earlier inquiry that concluded ‘We recommend that the DfE take further steps to strengthen the regulations for governance in academy trusts.’ (Written evidence to the current ESC inquiry can be accessed here).

To ensure the governance of academies is meaningful, we need to identify a democratic alternative.

Participatory governance

Participatory governance aims to stimulate the energy and influence of citizens in the governance arrangements of organisations that are important to them. In schools, it is about capturing the skills and interests of local stakeholders and creating a system that actively encourages and values their participation. A fundamental characteristic of this form of democracy is that it is a ‘bottom-up’ structure that creates channels for stakeholders to become involved in decision-making processes. A further feature is that these decision-making processes are ‘deliberative’, whereby participants listen to one another to generate group choices that are not merely interest-led.

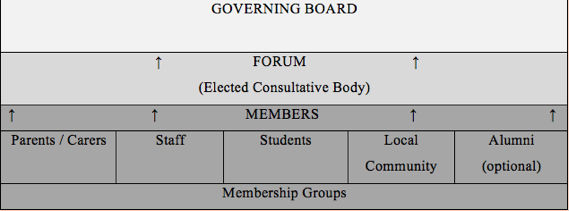

The Co-operative College has developed a governance model (below) that is participatory, and one that is rapidly gaining popularity, although Co-operative academies currently represent less than 1% of academies nationally. Co-operative principles include voluntary open membership, democratic member control, and a concern for the community. Local people are encouraged to join a membership group which, in turn, elects a Forum – a powerful consultative body of the elected governing board. This structure is reminiscent of earlier forms of community representation and participation – the Members’ Associations of Henry Morris’ Village Colleges in Cambridgeshire, for example.

The Co-operative governing board comprises a minimum of ten governors, though in practice it is likely to be more. Moreover, the board includes staff, parents, community members, the local authority representative, Co-operative College representatives, representatives from partner organisations, the headteacher and co-opted members. Realistically, in this model there is little room for the kind of small, self-elected, hero-leadership group that may emerge in academised governance models.

My research findings indicate the Co-operative model of governance is effectively preventing a democratic deficit emerging. Governing boards in such models are also much larger than current government recommendations, at around 20 members. This can be very important in order to share demanding workloads. Interestingly, this view is consistent with a 2014 study headed by Chris James from the University of Bath which linked higher performing schools with larger governing boards.

A criticism – and one frequently made by government – of such democratically-elected ‘stakeholder’ boards is that it is not who you represent that is important, but rather the skills the governor possess. My case study research indicates that within the larger elected stakeholder board there is no shortage of essential skills and experiences. Critically, there is the inherent structural capacity to govern effectively.

Participatory governance arguably goes against current government policy. But it is a democratic imperative. Furthermore, it is a model empirically proven to be effective. As more and more state-funded schools gain independence from local authority control, we must sound a call for democratic accountability and bring our schools back into community ownership.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

Andy Allen is a doctoral candidate at the Centre for Strategy and Leadership, Teesside University researching governance. He is an experienced teacher and community educationalist who has worked with governing boards for almost 20 years. For further information on the research please contact Andy at allenandy2015@outlook.com

Andy Allen is a doctoral candidate at the Centre for Strategy and Leadership, Teesside University researching governance. He is an experienced teacher and community educationalist who has worked with governing boards for almost 20 years. For further information on the research please contact Andy at allenandy2015@outlook.com

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.