‘Mum-of-two, 40’: but women rise to the top in Northern Irish politics

Women now lead three of the five main parties in Northern Ireland and make up 30% of the Assembly. Danielle Roberts looks at the sea-change in women’s participation in Northern Irish politics since the Good Friday Agreement, which has happened in spite of the lack of Unionist female politicians. While a number of BME and LGBT candidates stood in the 2017 election, none were elected.

Michelle O’Neill, leader of Sinn Féin in Northern Ireland. Photo: Sinn Fein via a CC-BY 2.0 licence

The March 2017 elections to the Northern Ireland Assembly were the second in just 10 months. The snap election – called after a financial scandal and allegations of corruption proved to be the final straw in an already tense political environment – brought into force reforms which reduced the number of seats in the Assembly from 108 to 90, with one seat removed from each constituency. Losses were inevitable, with mainly unionist parties taking the hit. However women’s representation slightly increased, as it has in each election since the first election to the Assembly in 1998.

The barriers women face in participating in politics are generally known as the 5Cs: cash, confidence, candidate selection, culture, and caring responsibilities (Galligan 2014). These apply to women across the board. Research carried out by the Northern Ireland Assembly and published in 2015 highlighted these issues, as well as logistical barriers such as the tradition of long hours, how female political representatives are portrayed in the media, and party-level issues such as candidate selection. Barriers particular to the NI context include fear, apathy and the adversarial nature of NI politics. Galligan notes that the NI conflict has been shown to have “a dampening effect on women’s political ambition”.

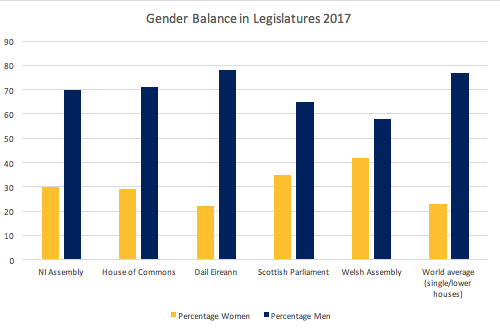

The Northern Ireland Assembly now has a greater proportion of women than the House of Commons (29%) and Dáil Éireann (22%). Women now make up 30% of the Assembly, an increase from 28% at the last election. The previous election in 2016 saw the number of women dramatically increase, from 19% in 2011. The percentage of women MLAs has more than doubled in under 20 years, from just 13% women in the first Assembly in 1998 (Ark 2002).

Women’s electoral representation remains low at other levels in Northern Ireland. Only 11% of MPs elected in 2015 are women and 25% of councillors. What is particularly notable about the performance of women in this election is that the percentage of women went up while the number of seats went down. In the context of the removal of one seat per constituency, even the small 2% increase in the number of women is a bigger achievement than the raw numbers may suggest.

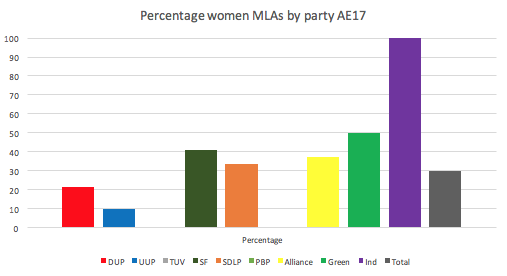

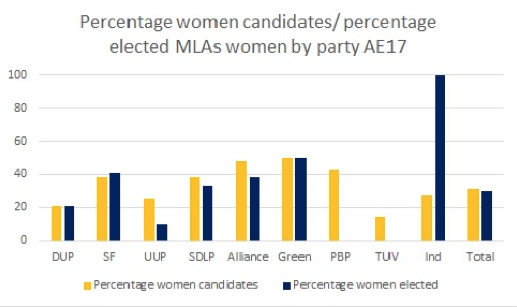

It has been observed that women typically perform better in multi-seat constituencies, both in terms of being elected, and being selected to stand in the first place. The percentage of women candidates increased this election to 31% from 27% in 2016. The Green Party fielded 50% women and 50% men for the second time. Sinn Féin, Alliance and the SDLP were not far behind, all at around 40%. The two biggest unionist parties lagged behind with the UUP at 25% and the DUP at 21%. Even though three outgoing DUP MLAs did not stand for re-election, as well as Johnathan Bell who had resigned from the party due to whistleblowing on the financial scandal and stood as an independent, not one of them was replaced by a woman candidate. Despite this the percentage of DUP women MLAs elected stood firm between 2016 and 2017 elections at 21%, even with the losses suffered by the party.

This disparity in candidate selection across the ethno-national divide is not new. In the Westminster 2015 election, only three of the 31 (around 10%) candidates from the main Unionist parties are women, far lower than the overall percentage of women candidates across Northern Ireland, which was around a quarter. In the first Assembly election in 1998, only 17% of candidates were women (ARK 2002).

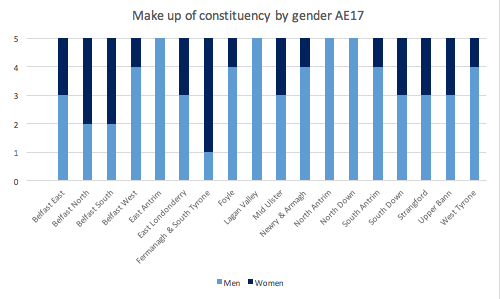

Women candidates received 32% of first preference votes: this is in line with the number of women candidates and suggests that the electorate as a whole is ‘gender blind’ when it comes to choosing whom to vote for. Two pregnant women were elected, perhaps reflecting a changes in attitudes about where exactly women ‘belong’. There were several openly LGBT+ candidates – yes, all letters were covered, with Ellen Murray, who was NI’s first transgender candidate in 2016, standing again in West Belfast for the Green Party. There were also a number of candidates from ethnic minorities. None were elected. In spite of these strides forward by women in terms of selection and election, four constituencies elected only men. Two of them, North Antrim and East Antrim, have never had a woman MLA since the Assembly’s inception in 1998.

Currently three of the five biggest Northern Ireland parties are led by women. As well as prompting media coverage of what party leaders wore to vote, the women in these positions seem to prove the adage that women politicians have to be exceptional, whereas men need only be adequate. Whereas all three women leaders topped the poll in their constituencies, Colum Eastwood was elected third in Foyle. Robin Swann has recently been announced as the new leader of the Ulster Unionist Party: he previously held the post of Chief Whip. With six years as an MLA, the 2017 Assembly election was the third he had contested, and he was elected second in North Antrim after 6 rounds of counting.Michelle O’Neill received more first preference votes than any other candidate in 2017, taking the title from Arlene Foster who received the most first preference votes in 2016.

Whatever your politics, the female party leaders each boast considerable political experience and achievement. Naomi Long of the Alliance Party served as Lord Mayor of Belfast and a term as the first Alliance Party MP ever elected, before being promoted from deputy to leader. From more than doubling her party’s vote in East Belfast in 2007, she topped the poll in the constituency in 2017. Michelle O’Neill, the Sinn Féin party leader was one of five Sinn Féin women to top the poll in their constituency in 2017. Her track record includes being the first woman Mayor of Dungannon and South Tyrone and terms as Minister of two different departments. Of her 10 years as an MLA prior to her appointment as leader, O’Neill has spent seven of them at the executive table.

The DUP leader Arlene Foster also topped the polls in Fermanagh and South Tyrone for the second election in a row. Initially elected as a MLA for the Ulster Unionist Party in 2003, she joined the DUP in 2004 and held three ministerial positions before taking up her position as First Minister in 2016, the first woman to hold the post. In comparison, the SDLP leader Colum Eastwood was the youngest mayor of Derry City Council but had only been an MLA for four years before successfully contesting the leadership. The outgoing leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, Mike Nesbitt, was mainly known as a news broadcaster prior to being elected as an MLA in 2011. Before his election his political CV consisted of 2 years as a Commissioner for Victims and Survivors and an unsuccessful bid in the 2010 Westminster election; he became leader in 2012, just one year after being first elected as MLA.

Even with such impressive CVs, there are still some who would rather lead with the fact Michelle O’Neill’s is a ‘mum of two (40)’ , or remind Arlene Foster that her most important role is as a ‘wife, mother and daughter’ not as leader of a political institution. We may yet see both the First and Deputy First Minister positions being held by women, although that is in no way certain, and talks are ongoing at the time of writing. While 30% female representation verges on critical mass – typically, when a third of an institution is made up of women we can expect to see some change in its operation – it still is not enough for Stormont to be considered gender-balanced. The Assembly is also overwhelmingly white and straight: there are no openly LGBT+ MLAs, and no BAME candidates were elected in either 2016 or 2017.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

Danielle Roberts (@DaniRNI) is a third year PhD candidate at Ulster University. Her work focuses on the barriers to political participation particularly experienced by women from the Protestant, unionist, and/or loyalist communities.

Danielle Roberts (@DaniRNI) is a third year PhD candidate at Ulster University. Her work focuses on the barriers to political participation particularly experienced by women from the Protestant, unionist, and/or loyalist communities.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.