The case of the missing marginals: how big will May’s majority be?

A little-reported result of the 2015 general election was a substantial reduction in the number of marginal seats, and a consequent increase in the number of very safe ones for both the Conservatives and Labour. Ron Johnston, Charles Pattie and David Rossiter explore the implications of those changes for the forthcoming election. Will May get the landslide the polls suggest?

Lib Dem leader Tim Farron attempts to win over a future voter in Southwark, a Labour-Lib Dem marginal. Photo: Liberal Democrats via a CC-BY-ND 2.0 licence

The snap general election called for 8 June has been presented, by the Prime Minister herself as well as many commentators, as an opportunity for the Conservative party to increase both its own majority in the House of Commons and also the majority there supporting the government’s policy on the Brexit negotiations. But how big might that majority be? Might she be disappointed, despite what the opinion polls are currently suggesting?

The Conservatives won 330 seats at the 2015 general election, giving them a lead of 98 seats over Labour but an overall majority of just eleven (excluding the Speaker), although with Sinn Féin members not taking their seats and with support on many issues from the DUP, the situation was a little more comfortable. However, May clearly hopes for more – and she is unlikely to get much joy in Scotland where, despite the growth in support for the Conservatives under Ruth Davidson’s leadership, few seats are likely to be won; nevertheless, Labour’s continued travails there mean that it is unlikely to make many Scottish gains either.

May’s potential problem is that although she currently has a substantial lead over Labour in the polls, capitalising on that at the election might not bring a commensurate increase in the number of Tory MPs. A major feature – not always recognised by commentators – of the 2015 election was a substantial reduction in the number of marginal seats, largely as a consequence of the collapse in support for the Liberal Democrats. Indeed the number of marginals – those won by less than ten percentage points – was at its lowest level since the Second World War. After the 2010 election, there were 194 seats in Britain with a gap of less than ten percentage points between the first- and second-placed parties; after the 2015 election there were only 120, a reduction of more than one-third in those that can be captured by a swing of no more than five points.

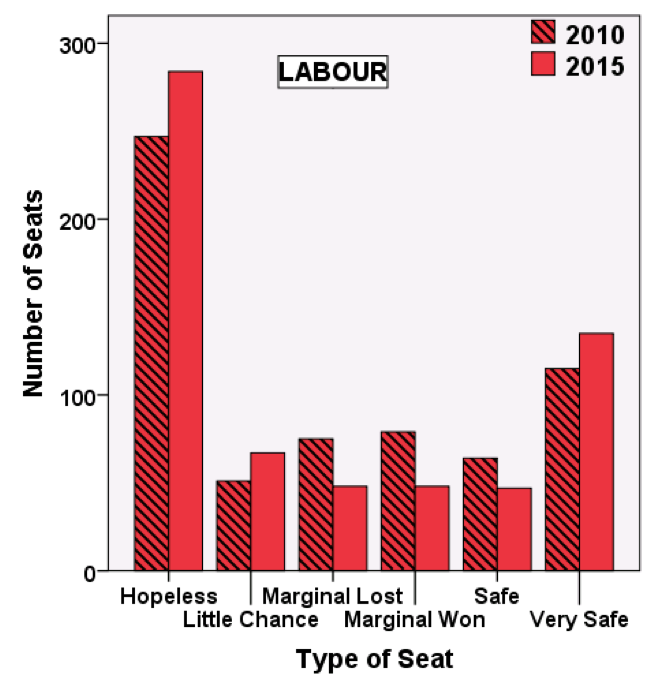

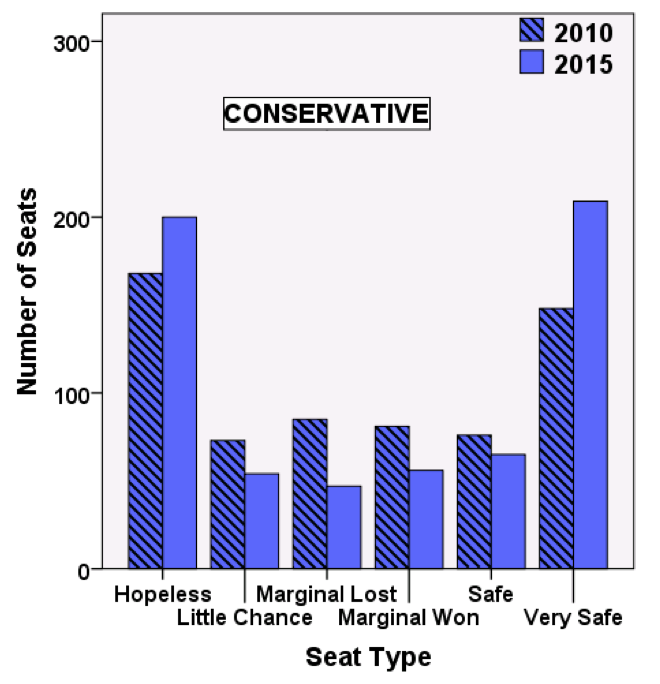

The two graphs illustrate that changed situation for the Labour and Conservative parties. Seats are divided into six types: Hopeless – lost by more than 20 points; Little Chance – those lost by 10-20 points; Marginal Lost – lost by 0-10 points; Marginal Won – won by 0-10 points; Safe – won by 10-20 points; and Very Safe – won by more than 20 points. Each party experienced an increase in the number of Hopeless and Very Safe seats between the 2010 and 2015 elections, and a decrease in the Marginal Won and Marginal Lost types. The country became more polarised between the two largest parties in 2015 than was the case at any previous post-1945 election: the Conservatives and Labour have more Very Safe seats than before, and are contesting fewer marginal ones – and of the 56 seats won by the SNP in 2015, 28 are classified as Very Safe and a further 18 as Safe.

How many of those marginals could boost May’s majority and give her the firm mandate she seeks? Fully 56 are seats were won by the Conservatives in 2015, 44 of them with Labour in second place. She is unlikely to lose any of them. Another 42 were won by Labour with the Conservatives second. If the Conservatives were to win them all, their seat tally compared to 2015 would go up to 374 and Labour’s would fall to 188 – a lead of 186 and a majority over all parties of 99, a very comfortable situation. But winning all 42 of those seats might be a tall order: Labour won 24 of them with a majority of more than 5 percentage points and, as was the case in similar constituencies two years ago, might expect to retain at least some of them through intensive defensive campaigning.

May’s hopes of unseating Labour in those 42 marginals could rest substantially on what happens to UKIP support. On average, UKIP won 15.7 per cent of the votes there in 2015. If the Conservatives can convince more than half of them that, as they are now implementing Brexit according to UKIP voters’ wishes, the latter should now switch their support to the party determined to ‘get our country back’ from the EU, then winning many if not all of the 42 is a strong possibility.

One possible threat, however, might be a resurgence in support for the Liberal Democrats, in part as a rebellion against Brexit and its hard implementation. But any increase in support for the Lib Dems – on the foundation of an average of only 3.7 per cent of the 2015 votes cast in those Labour-Conservative marginals – is at least as likely to disadvantage Labour (presented to pro-Remainers as weak on the issue) as the Conservatives.

A Liberal Democrat resurgence could be more dangerous to the Conservatives elsewhere, but the potential for many seats changing hands is small. There were only ten marginal seats where they came second to the Conservatives in 2015, losing by less than 10 percentage points. Three of them are in London and five in the southwest (the others were Eastbourne and Lewes). The Liberal Democrats might regain Kingston & Surbiton, Sutton & Cheam, Twickenham, and Bath, and hold on to their by-election gain last year in Richmond Park – all but Sutton & Cheam delivered large majorities for Remain at the 2016 referendum, and Lewes also delivered a small majority for staying in the EU. But voters in Eastbourne, St. Ives, Thornbury & Yate, Torbay, and Yeovil all favoured Brexit and it may be difficult for the Liberal Democrats to regain sufficient support there to unseat the Conservative incumbent only two years after the 2015 disaster.

There were only three Labour-Lib Dem marginals in 2015. The Lib Dems might be able to win back both Bermondsey & Old Southwark, where 73 per cent voted for Remain in 2016, and Cambridge (74 per cent Remain), but Burnley, which voted by 2:1 to Leave the EU and where UKIP got 17 per cent of the votes in 2015, would be a taller order.

And what of the 12.7 per cent of voters who supported UKIP in 2015? Is it now a party without a mission after the referendum result? Its current leader is targeting Labour-held seats in the north of England where there was strong support for Brexit, but he failed to make much headway recently at the Stoke Central by-election and his party lost a lot of ground at the Copeland by-election. In 2015 there was just one seat – Hartlepool – where UKIP’s candidate came second to Labour’s by a margin of less than 10 points, plus a further four (including Stoke Central) where the gap was between 10 and 20 points. Without a major surge of support for UKIP based on strong local campaigns and, probably, some tactical voting plus traditional Labour voters abstaining, the probability of more than a handful of Labour seats falling to UKIP is small, therefore. Similarly, there is only one seat (South Thanet) where UKIP came second to the Conservatives by less than 10 points in 2015, and a further five where the gap was between 10 and 20 points. A substantial UKIP presence in the next House of Commons is unlikely.

Much is to be played for in the six weeks of campaigning, and much will depend on how well the parties are prepared, nationally and locally. Is UKIP in a good state to fight a national campaign? How much money can Labour raise quickly to defend many of its marginals? The party was put on a war footing nationally a few weeks ago, but is it well-prepared to fight/defend in lots of places? Will the Lib Dems be able to fight strong campaigns on the doorsteps in more than a relatively few constituencies?

That May’s gamble will pay off and she will be returned with an increased majority seems very likely, despite the pessimism of some commentators. It will be surprising if her party’s lead over Labour is not increased by at least 30 seats, which will probably ensure a Commons majority of about 90 – a solid foundation for the 2022 election, which will probably be fought in new constituencies likely to boost the Tory lead over Labour by at least another 20 seats despite the reduction by 50 in the number of MPs. A substantial Liberal Democrat revival could cut into that gain slightly, but not by very much; there is too much ground to be made up.

In the end, a lot will depend on how many of the seats Labour won by 5-15 percentage points last time it can manage to hold on to. If many of its erstwhile voters there either stay at home or switch to the Tories or UKIP, then a Tory landslide victory could be the outcome – although, thanks to the SNP’s current hegemony, not quite of the magnitude Mrs Thatcher won in 1983. Jeremy Corbyn could outperform Michael Foot – just!

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit.

Ron Johnston, Charles Pattie and David Rossiter have written extensively on British elections. Their analysis of marginal seats presented here is based on a paper about to appear online in the journal British Politics.

Ron Johnston (left) is a Professor in the School of Geographical Sciences at the University of Bristol.

Ron Johnston (left) is a Professor in the School of Geographical Sciences at the University of Bristol.

Charles Pattie is a Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Sheffield.

Dr David Rossiter has worked in a research capacity at the Universities of Sheffield, Oxford, Bristol, Leeds and Essex. He has been involved in the redistricting process both as academic observer (for example The Boundary Commissions, MUP, 1999) and as advisor to the Liberal Democrats.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.