Book review | Under the Shadow: Rage and Revolution in Modern Turkey

In Under the Shadow: Rage and Revolution in Modern Turkey, Kaya Genç draws upon a range of interviews undertaken following the 2013 Gezi Park protests, bringing to light the diverse perspectives of different members of Turkish society at a time of division and dissent. Genç’s innovative use of oral history makes for a fascinating and magnetic read that particularly deserves praise for giving voice to young Turkish dissidents, writes Nikos Cristofis.

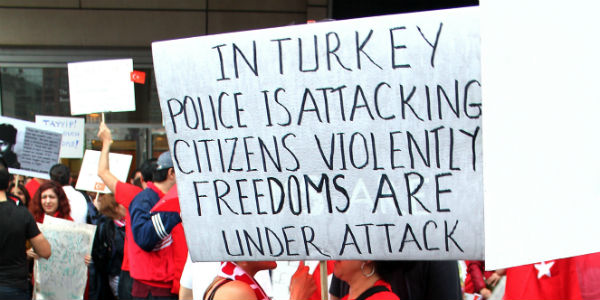

People in Chicago demonstrate in support of the Gezi Park protests in 2013. Photo: Ceyhun (Jay) Isik via a Cc-BY-SA 2.0 licence

Under the Shadow: Rage and Revolution in Modern Turkey. Kaya Genç. I.B. Tauris. 2016.

The Gezi Park protests that took place in Istanbul in late May 2013 started when a small environmentalist group protested the neoliberal ‘urban renewal’ plans of the AKP (Justice and Development Party) and then-Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to protect Gezi Park, one of the few green areas in Taksim. The Gezi Park project was just one of many sell-off plans initiated by the AKP to reshape Turkey and make it more actively part of the neoliberal market economy. In a purely symbolic act, the protests started exactly one month after the suppression of the 1 May demonstrations. Quickly they took on unprecedented proportions to become a mass social movement. In their brutal repression of the protests, the police burned tents and belongings. The violence unleashed by the authoritarian state triggered large-scale support for the demonstrators, and within hours it had transformed into Turkey’s largest anti-government movement in decades, inspiring protests in all of the country’s larger cities. In short, a minor event—the protests at the park—led to a widespread social uprising that faced unprecedented police violence backed by undemocratic statements by the Turkish Prime Minister that stand as testament to his authoritarian tendencies.

The Gezi Park protests that took place in Istanbul in late May 2013 started when a small environmentalist group protested the neoliberal ‘urban renewal’ plans of the AKP (Justice and Development Party) and then-Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to protect Gezi Park, one of the few green areas in Taksim. The Gezi Park project was just one of many sell-off plans initiated by the AKP to reshape Turkey and make it more actively part of the neoliberal market economy. In a purely symbolic act, the protests started exactly one month after the suppression of the 1 May demonstrations. Quickly they took on unprecedented proportions to become a mass social movement. In their brutal repression of the protests, the police burned tents and belongings. The violence unleashed by the authoritarian state triggered large-scale support for the demonstrators, and within hours it had transformed into Turkey’s largest anti-government movement in decades, inspiring protests in all of the country’s larger cities. In short, a minor event—the protests at the park—led to a widespread social uprising that faced unprecedented police violence backed by undemocratic statements by the Turkish Prime Minister that stand as testament to his authoritarian tendencies.

Under the Shadow: Rage and Revolution in Modern Turkey, authored by Kaya Genç, is a day-to-day account of the Gezi protests that offers insights into the mindsets of the range of young Turks that took part in the resistance and examines the complex dynamics that shaped mentalities at the time. Under the Shadow lends an ear to the Turkish people, specifically the youth, as a way of bringing to light their thoughts and perspectives as regards the protests and Turkish society in general.

Indeed, based largely on oral accounts, i.e. interviews with young dissidents who were involved in one way or another with the Gezi protests, the book tells us less about events and more about their meaning. As such, the interviews often reveal either unknown events or unknown aspects of known events, and cast new light on unexplored areas of the daily life of the non-hegemonic classes. In this sense, the book’s approach evokes Alessandro Portelli’s observation that oral histories can provide historians with new ways of understanding the past, not just in terms of what is recalled, but also with regards to continuity and change in the meaning given to events (Portelli in Perks and Thomson 2006).

The backgrounds of the people who participated in the protests varied widely, ranging from young leftist activists, like 21-year-old Cenk Yürükoğulları and his friends (27-37), to people like Beybin Somuk, an animal rights campaigner and project manager at the NGO Genç Siviller (Young Civilians), who initially treated the Gezi protests with suspicion (37). She feared that they would lead to an outbreak of civil war as she watched the news on CNN International whilst in The Netherlands; when she returned to Turkey, she realised that was not the case at all. For Somuk, the politicisation of the protests (in the sense that the young people who participated would soon fall under the hegemony of particular political groups) led her to not participate.

The following two chapters are devoted to young artists (Chapter Three) and journalists (Chapter Four). Aytuğ Akdoğan, a 22-year-old underground poet, Lara Fresko, a young artist who was conducting research for a show at SALT in Istanbul, and the filmmaker Can Evrenol are some of the figures that are given a central role in the former, and Berke Gol, Berkan Ozyer and Betul Kayahan in the latter. The personal stories of all these figures are very much of interest: for example, Fresko’s experiences of being the recipient of racism and discrimination from an early age, which contributed to her politicisation. Aytuğ, on the other hand, a young ‘White Turk’ and apolitical youngster who nonetheless has deep awareness of the social and political inequalities of Turkish society, became highly politicised through his participation in the protests, and even more in the months that followed. He wrote his first poetry book years before the protests when he was just 17 years old; not long after, he moved out of his parents’ home. After being falsely accused of attacking a police officer, his experience of the judiciary system for over eighteen months after the Gezi protests made him see things differently. Aytuğ was finally acquitted, but he had to pay a heavy price: unable to make ends meet, he moved back with his family to the site, the housing developments inside the city protected by private security guards. Isolated from the rest of the world, it is these that contribute to making the young people of Turkey apolitical: cut off from different social classes and socialising only with one another.

Equally of interest is the final chapter concerning ‘Turkey’s angry young entrepreneurs’: one of the central elements of the AKP’s power base. Indeed, when the party first came to power, it offered new hope backed by conservatism, pro-EU policies and the maintenance of Turkish-US relations. These elements all blended together with avid capitalism largely based on the construction sector. As the author rightly states: ‘the Turkish state and industrialists are twins born in the same instant’ (187). The author’s account, however, gives the impression that the construction sector is a well-oiled machine free of scandals and without ties to the government, which is not the case.

Genç’s historical knowledge is evident within the book by his bolstering of information about Ottoman and Turkish history to frame the context of the recent developments in Turkey and to offer an explanation for the rise of young dissident voices. In that respect, as one of the most critical issues of performing oral history is that of verification, the author manages to create a well-balanced account of the events that transpired and offers an impartial analysis that is generally not being swayed by the personal experiences of the interviewees.

Although in general the author does an exemplary job of describing events, there are points where clarification should nonetheless have been made. To name just two, firstly Genç implies that the coup of 1980 took place as a means of re-securing secularism. As he writes: ‘the armed forces brought Turkish society back to its Atatürkian factory settings’ (4). At the same time, however, through the ‘Turkish-Islamic Synthesis’, there was also an attempt to unite the country against the ‘enemy of the state’ (e.g. communism) by putting Islam at the centre of Turkish identity and history, thus opening the way for the rise of political Islam in Turkey and today’s ruling party. Although that point is an issue of perspective and interpretation, the author’s argument that Doğan Avcıoğlu theorized the rise of the MDD (National Democratic Revolution) in the early 1970s is plainly false. A major ideological break within the Workers’ Party of Turkey (TİP, 1961-71) became apparent in 1966 at the Malatya Congress, but the MDD’s first manifesto, albeit perhaps in primitive form, had already been made public by Mihri Belli, the leader of the MDD, who used the pen name Mehmet Doğu in an article he wrote for the review Yön (Direction) in 1962.

Under the Shadow is nonetheless a fascinating book written using magnetic language. Genç largely manages to avoid getting carried away by his own ideological views or those of dissidents. It is also the first book of its kind to use oral history as a methodological framework and to give voice to a mosaic of young Turkish dissidents, making it well worthy of praise.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It first appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Nikos Christofis received his PhD from the Institute for Area Studies (LIAS), Leiden University, in 2015. His dissertation has the title, ‘From Socialism via Anti-Imperialism to Nationalism. EDA – TİP: Socialist Contest over Cyprus’. Read more by Nikos Christofis.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.