Who’s going to hold the new metro mayors to account?

Six English mayors will be elected on 4 May. They will enjoy extensive new powers. But who will hold them to account? Unlike in London, no directly-elected assembly will scrutinise the mayors’ action. Chris Terry warns that councillors need to step up to the role – and the method of electing councils themselves makes this deeply problematic.

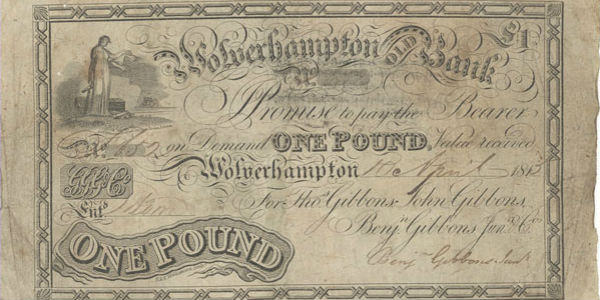

A £1 note issued by the Wolverhampton Bank in 1815. Photo: WAVE Galleries via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence

This month sees local elections in Scotland, Wales and parts of England – contests which have been inevitably eclipsed by the snap general election. But perhaps the most significant of these contests will be the first six ‘metro-mayors’ elected in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, Greater Manchester, the West Midlands, the Liverpool City Region, Tees Valley and the West of England.

These are powerful new posts, representing areas with millions of voters and with powers over areas such as transport, the local economy, and, in Greater Manchester, even aspects of the local NHS.

The mere election of a mayor, however, does not mean these new mayoralties are automatically democratic. Mayors work within combined authorities, with cabinets made up of council leaders – all of whom are indirectly elected through a broken First Past the Post voting system.

But there is no directly elected assembly to hold them to account, like that of the London mayoralty. Instead, the Mayor is scrutinised by Overview and Scrutiny Committees made of councillors and within the council chambers themselves. This means who sits on those committees really matters.

At the Electoral Reform Society, we want to see a better democracy. And the metro mayors are the biggest change to the governance of England in decades. They are an exciting opportunity to change the way our cities are governed to be more inclusive, more local and more visible.

But we are concerned that this structure passes up existing legacies of problems in local government to the new mayoralties, as we point out in our new report From City Hall to Citizens’ Hall: Democracy, Diversity and English Devolution.

Due to our electoral system, Britain has a multitude of local ‘one-party states’, with almost no opposition in the council chamber. Many of these abound in the areas electing metro-mayors, with some councils having just one member from outside the controlling party.

Previous work for the ERS has shown that these councils risk an extra £2.6bn on public procurement each year, due to a lack of scrutiny.

Concerns around scrutiny are particularly strong in some of the metro-mayor areas because the council leaders – who will make up the cabinets – lack any diversity whatsoever. Only two of the council leaders of the six areas electing combined authorities are women. Only one is from a BAME community. This carries with it risks within the policymaking process, narrowing the experience and knowledge-base around the cabinet table.

So far the combined authority scrutiny committees have also demonstrated a lack of diversity, both political and demographic. On the West Midlands Overview and Scrutiny Committee, for instance, ten of twelve political members are drawn from one party, and ten are men.

So how do the new bodies improve the scrutiny situation?

First, without a directly-elected chamber, scrutiny from outside City Hall becomes even more important, especially with the decline of local news media as an investigative force. Transparency must therefore be carefully woven into the culture and behaviours of combined authorities so that news media, the public and, indeed, those working for the combined authority have the most accurate information about it possible.

Secondly, the electoral system for English local government should be changed to the Single Transferable Vote version of proportional representation used in Scotland for local elections. This system better reflects the reality of modern local government, in which scrutiny of powerful new offices of state is becoming more important – not just of combined authorities but also of outsourced contracts, clinical commissioning groups, Police and Crime Commissioners and local boards and quangos.

In the meantime, overview and scrutiny committees should reflect the local vote, rather than the political balance of seats and should be gender balanced.

Finally, these combined authorities are also an opportunity to democratically experiment. Deliberative democracy techniques, such as citizens’ juries and assemblies can provide ideas and feedback from diverse groups of voters with a surprisingly sophisticated level of discussion, by providing randomly selected citizens with a chance to deeply interrogate issues. We showed that it worked when we conducted two citizens’ assemblies on English devolution.

And digital democracy techniques, such as the participatory budgeting used in Paris, Madrid and Reykjavik also provide new potential ways of interacting with the public.

There are two ways English devolution could go. The new mayoralties could, at their worst, create a new elite, distant from voters and doing politics to them, rather than with them. Or they could be seized as an exciting new opportunity to do politics differently. We hope the new mayors use this chance to truly bring power closer to voters.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

Chris Terry is a Research Officer at the Electoral Reform Society.

Chris Terry is a Research Officer at the Electoral Reform Society.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.