How the Eurosceptics brought down David Cameron: a serious case of supplier lock-in

David Cameron’s decision to call a referendum on the EU was the result of intense Eurosceptic pressures from both within and outside his party. He found himself with little scope for manoeuvre as Ukip gained support and his backbenchers threatened rebellion. Pascal D König looks at what a competition theory usually applied to business can reveal about his misjudgment and eventual replacement as PM.

Eurosceptics to the right of him … Michael Gove, who campaigned to Leave the EU, with David Cameron in 2010. Photo: Number 10 via a CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence

Businesses have a tricky relationship with their suppliers. Generally, they prefer to keep them at arm’s length and avoid giving them too much influence, because too much dependence on a single supplier is risky. If that supplier becomes aware it is indispensable, it may be able to dictate the terms of the relationship or even threaten a business by putting up its prices.

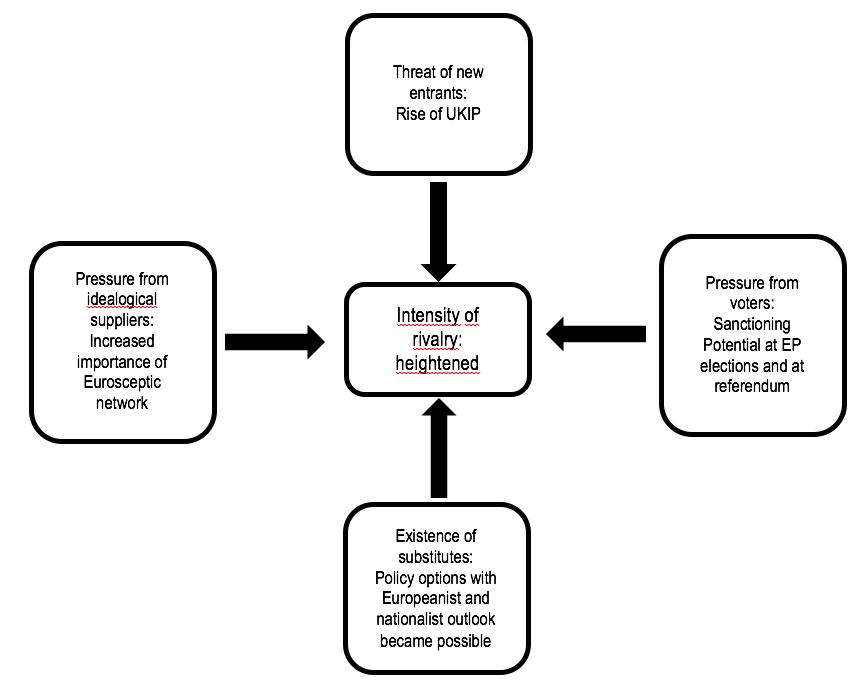

But supplier influence is only one of the competitive forces acting on a business. The management theorist Michael Porter identified five of them:

• suppliers’ bargaining power

• customers’ bargaining power

• the threat of substitutes

• the threat of new entrants

• the intensity of rivalry in the market, which is influence by the other four.

Porter originally conceived this as a framework for analysing the level of competition within an industry, though it can also be used to develop a strategy to successfully position a product in a market. However, it is also possible to identify these forces at work in the realm of party competition. In the Conservative party under David Cameron, their conjunction brought about a complex competitive environment – an environment in which ideational suppliers were pivotal.

The Conservatives faced a threat from a newly-popular competitor, Ukip. Over time different means and policies emerge to tackle political issues – take, for example, monetarism replacing Keynesianism as a paradigm in economic policy. The customers – here, the voters – exert additional pressure if elections are close, there is a clear majority behind certain policies or they can threaten backward integration, which in politics would mean they have direct democratic means to take things into their own hands.

Suppliers in the area of party politics can take various forms. Parties are often traditionally tied to certain ideational suppliers, such as associations, trade unions and churches. They may also depend on influential supporter groups, activists and sponsors, which can constrain the party leadership.

Finally, party rivalry is considerable, and raises the stakes for parties to invest in an issue where no party is clearly more competitive and where voters are volatile and available, i.e. do not take a principled stance on something.

In politics, enjoying a competitive advantage means being perceived as more credible, competent and committed than others, and sustaining that impression. As competition increases, the effort needed to achieve and sustain competitiveness rises too. Looking at parties striving for a competitive advantage against the backdrop of the five forces can help to make sense of the developments that led up to Brexit and its aftermath.

Setting the scene

The foundations for Brexit and Cameron’s resignation were laid during the financial crisis. During that period, financial and economic policy – as well as immigration policy – became strongly intertwined with European Union politics. The financial crisis suddenly put economic issues at the top of the political agenda; immigration gradually replaced them there.

As Cameron implemented austerity policies, his government deliberately distanced itself from the EU. The latter made an easy scapegoat in the light of its handling of the Eurocrisis, and the British government witnessed a serious of policies on the EU level (such as the Two Pack, the so-called Sixpack and the Fiscal Compact) that put constraints on countries’ financial autonomy – and from which the UK opted out where it was concerned (as in the Fiscal Compact). Under these circumstances, the idea that Britain could sort out the crisis by itself, unconstrained by the EU and without sharing the burden of other EU members, gained currency – perhaps even more so as British austerity paradoxically looked very much like the Eurozone austerity model. As Marc Vail has argued, intra-party pressure and the threat from Ukip created incentives to complement an economic policy of strict austerity with vilifying the EU. According to Vail, the Cameron government demonised “the EU as an existential threat to Britain’s national sovereignty and an institutionalised threat to Britain’s economic well-being”. Economic policy and the stance towards the EU were interwoven.

It therefore became hard to keep economic and financial policy separate from the issue of EU relations. The question of the right policy solution became linked to the question of how and whether to stay in the EU – and so alternative policy paths towards prosperity emerged. Moreover, the idea of economic nationalism was strengthened, which played into the hands of Eurosceptic Conservatives. For them, the relationship with the EU is not only a question of British identity, but also about opportunity – or the sovereignty – to pursue a better economic development path.

In 2011, the Prime Minister was already under pressure from Conservative MPs who were calling for referendum on EU membership. In their view, the UK had surrendered too many powers to the EU, which was seen as bloated, wasteful, over-regulated and a barrier to economic growth. In 2015 a newly-formed group of 50 Conservatives demanded major concessions from Cameron’s renegotiations with the EU. The Tory MP Steve Baker, who led the group, warned that the government would only be supported as long as he obtained political independence from Europe, more freedom from regulation and a greater ability to trade freely.

Certainly, Eurosceptic Conservatives were influential before the crisis, with a long-standing and extensive network. A Eurosceptic consensus had been growing since the mid-2000s. However, their ideas and agenda became more important as austerity took hold. Euroscepticism was a relatively marginal issue before, but the developments during the financial crisis put it at the centre of party politics, and the question of EU membership was openly debated. As John FitzGibbon has identified, the Tory Eurosceptic network not only extends well beyond their MPs, but stretches beyond party lines and even encompasses financial supporters and the media. This gave them the ability to mobilise support outside of parliament. It also meant that they could, under certain circumstances, be in a position to bypass the party leadership formulation of policies – or as it is put in management theory, threaten forward integration.

While economic and financial issues were still high on the political agenda, the issue of immigration gradually rose in importance and demanded policy responses from the government. At the same time, immigration – in part combined with law and order – became tied to EU affairs, as many migrants had come to Britain when their countries joined the EU. As the combination of anti-immigration sentiment and Euroscepticism were becoming more popular, Ukip rose in the polls, putting additional pressure on the Cameron government.

How Cameron dealt with an intricate competitive situation

The Cameron government thus found itself in a difficult situation. Solutions to immigration and the financial crisis were increasingly hard to separate from the question of European integration. Competing merely on economic policy, for example, was not enough. To be truly competitive, it needed to signal competent and credible handling of EU affairs. Ukip was threatening the Conservatives not just on immigration, but also through its emphasis on economic nationalism and independence. Pressure also came from within Cameron’s own party, with Eurosceptic Conservatives playing an important role as an ideational supplier and thus effectively constraining Cameron’s scope for strategic decisions.

Then came the 2014 European Parliament elections, in which Ukip could – and did – achieve major success, having already made considerable gains in the 2013 local elections. Voter influence in terms of sanctioning potential was high, and Ukip was threatening to enter Parliament. Finally, while party rivalry is generally intense in the majoritarian and adversarial British political system, the 2010-15 coalition government and the relatively close majority after the 2015 general election meant additional competitive pressures.

Calling a referendum under these circumstances was a way to deal with these threats. It allowed Cameron to signal commitment and credibility in the issues of immigration and political and economic sovereignty from the EU. He basically tried to play voters against internal critics, which could have removed the EU from the top of the agenda again.

However, this move only bought Cameron more time, ensuring that voters would have a strong influence over EU affairs at a later stage. Moreover, his gamble ensured immigration and austerity/economic issues became even more closely associated with European integration – also visible in the 2015 Conservative manifesto, which promised to scrap the Human Rights Act and restrict benefits for EU migrants. As the referendum date came closer, it became more and more clear that neither side enjoyed overwhelming support among the electorate. At the same time, Cameron was in a tough competitive position. The Conservatives could hardly be presented as credible and committed supporters of the Remain position, particularly with Eurosceptic Conservatives and their supporters launching their own campaign. Other parties, while they also had splits on the EU issue within their ranks, were in a better position. The hard Eurosceptics and Brexiteers in Cameron’s own party made it virtually impossible for him to credibly take a pro-EU stance, which in turn meant it was harder for him to appear credible on immigration and the economy.

His previous strategic decisions thus limited Cameron’s ability to present himself as a party leader with a distinctive and competitive stance on the EU. Only after the referendum result did the Conservatives adopt a very clear stance, even showing a readiness for a hard Brexit. By becoming the party of Brexit and of “putting Britain first”, it could regain credibility. Cameron’s gamble, which is perhaps far from having reached its conclusion, thus led to a partial rebranding of the Conservatives. The party strengthened its association with economic nationalism and control over immigration – certainly an image and reputation that other parties can hardly achieve and challenge now.

While they now seem to enjoy a competitive advantage on those issues, the Conservatives will have to prove that their solutions continue to deserve support. Moreover, they risk ending up having a competitive advantage in an area – a market segment – that is popular with a declining number of voters.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

Pascal D. König is a postdoctoral researcher at the Goethe University, Frankfurt. His research focuses on political communication, political strategies, and party competition. Recent work centres on a comparison of governments’ policy communication and on strategic policy action.

Pascal D. König is a postdoctoral researcher at the Goethe University, Frankfurt. His research focuses on political communication, political strategies, and party competition. Recent work centres on a comparison of governments’ policy communication and on strategic policy action.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

This is a useful summary of what happened from David Cameron’s position. However what in fact happened of course is rooted in 30 years in which each different Prime Minister was impaled on the need to say one thing within the institutions of the EU and another thing ‘at home’. All of which combined to create a powerful quintet of Porter’s competitive forces over a very long time, enboldened though onle really over the past decade not just by the issues surrounding austerity but by the fact that the public and other players could no longer actually ignore what had long been specifically denied – that the EU was now a major player in terms of what an elected government could or could not do. That failure and the use of deception was referred to even by europhile commentators like the late Hugo Young as potentially fatal to the UK’s role in the EU.

As late as 2004, when I was vice-chair of UKIP, I regularly met people who told me “well there’s no way we want to go into Europe” (we were of course in “Europe” and what they were referring to was the currency – even otherwise intelligent people made that sort of remark but it was telling). Not any more – and it is not just down to vilification by politicians. Cameron spent the entire referendum campaign telling us how wonderful the EU was and how we would all end up in World War 3 if we disobeyed him.

The final point is, I think, very open to question on the basis of recent history. The author suggests that the Tories may risk having a competitive advantage in a declining segment of public support (I presume and hope I am not wrong that he means that older voters are more inclined to support Leave than younger voters…wastage etc).

However, and I have commented on this elsewhere, research shows that until a crucial point about 4 years ago, the younger voter was in all polling the second most eurosceptic group after the 65+. Indeed part of my role was to talk in schools and I was staggered at easy support for quitting the EU. There is no doubt that this has changed and quickly.

But then look at France, Hungary and other EU countries – there the older voter is the most pro-EU and the youngest voter (and even more, the upcoming 16+) are the most virulently opposed to the EU. The point is that you cannot take for granted that UK Generation Snowflake (unfair but understandable) is thinking much beyond its own relatively minor concerns on the EU as sold to them by politicians using a prospectus that instinctively strikes a chord. The EU’s appalling record in Greece and elsewhere could just as easily be turned against it to strike the exact opposite chord among those same young citizens.