Book review | The Tories and Television, 1951-64: Broadcasting an Elite

In The Tories and Television, 1951-1964: Broadcasting an Elite, Anthony Ridge-Newman reflects on how historical developments in television broadcasting have influenced the structure of UK political parties, focusing specifically on the Conservative Party between 1951 and 1964. Backed up by rigorous archival research and interdisciplinary in scope, this is a fascinating, persuasive read that will be welcomed by both political scientists and media historians, finds Antony Mullen.

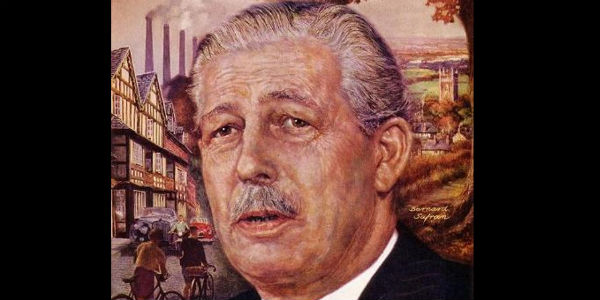

Harold Macmillan pictured by Bernard Safran in a 1959 edition of Time magazine. Public domain

The Tories and Television, 1951–1964: Broadcasting an Elite. Anthony Ridge-Newman. Palgrave Macmillan. 2016.

The 2010 and 2015 General Elections respectively saw the introduction and return of Prime Ministerial television debate formats in the UK. In 2016, these were incorporated into the EU referendum campaign, though it appears increasingly unlikely that they will return during the 2017 General Election. The debates have produced notable moments: Nick Clegg’s stardom in 2010, Ed Miliband’s declaration that he was ‘tough enuss’ to lead the country and Amber Rudd’s comparison of Boris Johnson to a dangerous driver. It is easy to assume that the relationship between UK political parties and broadcasters has mattered most in recent years, but Anthony Ridge-Newman’s book The Tories and Television, 1951-1964: Broadcasting an Elite convincingly shows that this is not the case. Ridge-Newman sets out to demonstrate not simply the ways that television has served as a means of political communication, but also the extent to which developments in television broadcasting have influenced the structure of political parties.

The 2010 and 2015 General Elections respectively saw the introduction and return of Prime Ministerial television debate formats in the UK. In 2016, these were incorporated into the EU referendum campaign, though it appears increasingly unlikely that they will return during the 2017 General Election. The debates have produced notable moments: Nick Clegg’s stardom in 2010, Ed Miliband’s declaration that he was ‘tough enuss’ to lead the country and Amber Rudd’s comparison of Boris Johnson to a dangerous driver. It is easy to assume that the relationship between UK political parties and broadcasters has mattered most in recent years, but Anthony Ridge-Newman’s book The Tories and Television, 1951-1964: Broadcasting an Elite convincingly shows that this is not the case. Ridge-Newman sets out to demonstrate not simply the ways that television has served as a means of political communication, but also the extent to which developments in television broadcasting have influenced the structure of political parties.

As the title suggests, The Tories and Television focuses primarily on the Conservative Party between 1951 and 1964, though it also offers significant insights into how Labour adapted to developments in television during this period. It is the second book, following Cameron’s Conservatives and the Internet: Change, Culture and Cyber Toryism, in which Ridge-Newman demonstrates his ability to comfortably straddle media studies and politics. In both, his aim is to explore how new technologies have influenced the ways the Conservative Party communicates with the country. In The Tories and Television, he does this by focusing on five case studies, each centred on one of the four Prime Ministers of the period: Winston Churchill, Anthony Eden and Alec Douglas-Home as well as two on Harold Macmillan.

Ridge-Newman’s approach is consistently interdisciplinary and backed up by rigorous archival research conducted at the Conservative Party Archive at the University of Oxford. The benefit of this approach, as he states, is that it allows for a more holistic consideration of structural changes within the party. In many ways, like most of us working on the Conservative Party, Ridge-Newman is indebted to the work of Tim Bale. Building on Bale’s research, Ridge-Newman investigates the drivers of structural and organisational change within the Conservative Party. Where Ridge-Newman marks out his own, new territory is in his specific focus on television – and this book tells us as much about developments in British broadcast media as it does the Conservative Party.

His sections on Macmillan’s premiership are most interesting. It was under Macmillan that two substantial transformations occurred in near-tandem: the increased number of ITV viewers meant that the ‘BBC’s monopoly eroded’ (88), and organisational change within the Conservative Party was rendered inevitable by ‘declining mass party culture’ (92). He argues that Macmillan’s Conservatives took advantage of these, recognising that television was a means of communicating with the electorate that would relieve the workload of grassroots members. Macmillan, unlike his predecessors Churchill and Eden, was sensitive to the importance of this burgeoning mode of communication and made efforts to firstly ‘control and, secondly, master it’ (89). Ridge-Newman is careful not to overplay Macmillan’s engagement with television, however, recognising that his motivation to embrace the new media was grounded in suspicion rather than enthusiasm.

Yet it was not just at the level of the party leadership that television changed Macmillan’s Conservatives. The campaigning arm of the party held more positive views about the Conservative brand as the party’s broadcasting abilities improved. As Ridge-Newman puts it, television was ‘an important tool for party morale’ (116). Backing up this claim, he draws upon archival evidence to highlight examples of improved self-confidence among party supporters and campaigners. According to one Conservative member, Macmillan’s talent in front of the camera had been of great encouragement to the party’s campaigners. This would become significant as the party leadership began to accept the ‘reality that they could no longer exert control over the broadcasters’ (122). What they could do, Ridge-Newman shows, was ensure that the right figure was sufficiently trained to represent the party and create the image that they desired. Ridge-Newman’s book covers various instances of increasing and foregoing control, but what we see here is the laying of the foundations of what many might consider to be a contemporary phenomenon: the ‘personality politician’.

Overall, the book would have benefitted from a more precise definition of ‘elite’ in the context of party organisation. The word appears in the book title and is used throughout, but at no point does Ridge-Newman make explicit his understanding of it. It is not always clear whether ‘elite’ is simply being used as a synonym for ‘leadership’ or ‘people of importance’, but Ridge-Newman evidently intends to use it in a more specific way than this. For example, when he refers to ‘the organizational and political elites of the three main parties’ (66), it is not obvious how or why we should judge a Conservative Prime Minister and Labour’s communications directorate to be, in the same sense, ‘elites’.

The book is published in the Palgrave Pivot format which, Palgrave states, allows authors to produce works that are longer than a journal article but shorter than the standard monograph. The format works in Ridge-Newman’s favour, allowing him to make a unique contribution to the study of the Conservatives and Conservatism. However, the editing of the book evidently required more attention: it is slightly marred by some obvious, distracting errors. Readers will no doubt notice more than ten occasions where necessary hyphens are missing; hyphens being used unnecessarily; several instances of no spacing between words; a ‘were’ which should have been a ‘was’ (68); and the misspelling of ‘descent’, among others (199). Similarly, the length of some sub-chapters was too short (the briefest being only a paragraph long). This interrupted the flow of the prose and gave a fragmented feel to parts of the book.

These observations, of course, do not detract from Ridge-Newman’s argument, which is intelligent and persuasive. In the opening, Ridge-Newman makes clear his intention to go beyond subject disciplines to provide a broader perspective than what has been offered in previous studies. He has undoubtedly achieved this, and has consequentially produced a book that would be equally at home on the bookshelves of political scientists and media historians. The Tories and Television is a fascinating and worthy read.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It first appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Antony Mullen is a PhD student and Pemberton Scholar at Durham University. Since March 2016, he has been the Convenor of the Thatcher Network (@ThatcherNetwork). He is also a Research Assistant in the Centre for Modern Conflicts and Cultures on a project investigating contemporary surveillance and intelligence-gathering cultures. He tweets as @AntonyMullen.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

For both main parties, the 8 years after Suez were a baptism of fire in regard to tv. TV in the early 60s surely had as much power as it does today, given greater saturation, fewer channels, bigger viewing figures and greater respect for the importance of the daily tv news broadcasts etc. Since then there is simply more competition.

Possibly more stark is the contrast in professionalism between the mid 50s and early 60s in the Labour Party’s approach to tv, and someone should do a work on that. Anyone who remembers the shambolic but hugely entertaining ’55 PPB by Harold Wilson and Edith Summerskill with melting butter and cheese to demonstrate food prices, forgotten lines, Wilson’s adlibs and shouting over each other (‘and don’t forget the butter, you’ve stuck the ticket in the wrong one, that’s the cheese’) and Summerskill sounding and looking very glam and sexy as they faded off the screen with Wilson just heard saying “…and don’t forget…”…and compare that with Wilson’s greater mastery in 64…