Audit 2017: How democratic is local government in Scotland?

Local authorities play key roles in the devolved government of Scotland, as the only other source of elected legitimacy and as checks and balances on the domestic concentration of power in Scotland’s central institutions. As part of the 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, James Mitchell and the Democratic Audit team explore how democratically local councils have operated.

Tartans at Lochcarron Mill in Selkirk. Photo: Gitta Zahn via a CC BY 2.0 licence

This article was published as part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy. We have now published: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit with LSE Press, available in all ebook formats. You can download the whole book for free, and individual chapters, including a fully revised version of this article.

What does democracy require of Scotland’s local governments?

• Local governments should engage the wide participation of local citizens in their governance via voting in regular elections, and an open interest group and local consultation process.

• Local voting systems should accurately convert parties’ vote shares into seats on councils, and should be open to new parties entering into competition.

• As far as possible, consistent with the need for efficient scales of operation, local government areas and institutions should provide an effective expression of local and community identities that are important in civil society (and not just in administrative terms).

• Local governments should be genuinely independent centres of decision-making, with sufficient own financial revenues and policy autonomy to be able to make meaningful choices on behalf of their citizens.

• Local governments are typically subject to some supervision on key aspects of their conduct and policies by a higher tier of government. But they should enjoy a degree of constitutional protection (or ‘entrenchment’) for key roles, and an assurance that cannot simply be abolished, bypassed or fully programmed by their supervisory tier of government.

• The principle of subsidiarity says that policy issues that can be effectively handled in decentralised ways should be allocated to the lowest tier of government, closest to citizens.

As in other parts of the UK, the authority and powers of Scottish local government were eroded over many decades prior to devolution. The major parties tended to argue for decentralisation in opposition but then to revert to centralising ways when in power. The absence of any constitutionally entrenched protections for local government meant that there were few impediments to this trend.

So there were many hopes that the establishment of a Scottish Parliament and Executive in 1999 would call a halt to local councils’ decline. The 32 local authorities have key delivery responsibilities covering most of the policy fields devolved to Edinburgh institutions, including:

- Mandatory services, such as education for students aged between 5 and 16, social work, and (initially) fire and rescue services.

- Regulatory functions, such as environment, public health, taxis, licensing of alcohol.

- Permissive activities, such as recreation and economic development.

A month after the first Scottish Parliament elections an all-party Commission (chaired by Sir Neil McIntosh, formerly chief executive of Strathclyde Regional Council) offered a comprehensive programme of reform. But the then dominant Labour elites in Scottish politics largely ignored the report, ensuring that centralisation broadly continued.

The SNP Minority Government elected in 2007 signed a Concordat with the Convention of Scottish Local Government that removed many of Scottish central government’s detailed controls over councils. But over time SNP ministers have tended to revert to the pattern of their predecessors in centralising power. Sometimes centralisation is borne out of Scottish government frustration that policies are undermined at local level, but at other times may reflect a ‘control-freak’ impulse to impose central policies. Whatever the reason, for local government there is actually little in Scotland’s constitutional set-up to prevent centralisation happening.

Recent developments

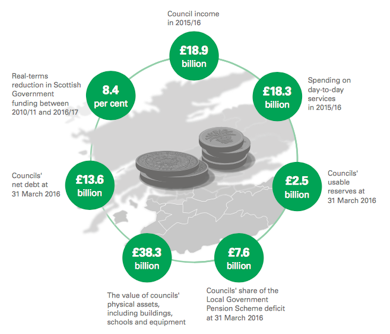

The biggest recent challenges facing Scottish local authorities are financial pressures from UK and Scottish government austerity policies, combined with increased demands for services, especially with an ageing population, and some increasing staff costs including pensions. As Chart 1 from Audit Scotland makes clear, all local authorities face funding gaps and either need to make further savings or make more use of their reserves. Some authorities are better placed than others to address these challenges.

Chart 1: Financial challenges for Scottish local government, 2016

Source: Audit Scotland 2016, p. 4.

At the same time, local authorities are struggling to develop better ways of working with separate Scottish public services (like the police, fire services and NHS hospitals and GPs) so as to deliver more effectively joined-up services. Occasional voices are still raised in favour of the wholesale reorganisation of local government. For example, the Scottish Greens advocate creating many more local community-based authorities, instead of the current 32 large and remote councils. However, there appears to be little appetite for any major reform push amongst the larger parties.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Scottish local councils are elected using the Single Transferable Vote, ensuring a spread of parties across local authorities. Since 2007 the previous pattern of one party dominance (benefiting mostly Labour) has pluralised at three successive council elections, to better reflect the balance of opinion in each area, though there are problems with its operation in sparsely populated areas. | Local authorities have no entrenched constitutional protection. Their roles, areas and even existence can be changed at will by a government with a majority in the Scottish Parliament. |

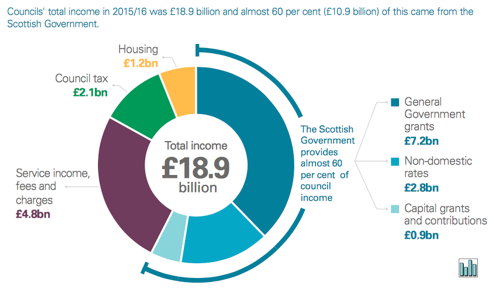

| There is a consensus on the broad principles of the key roles played by local governments across the main parties, although a highly adversarial party political battleground often obscures and undermines the degree of consensus. | The Scottish government provides well over half of local authorities’ revenues (see Chart 2 below), which creates a high level of dependency by councils, and inhibits their capacity for independent decision-making. |

| There is also a high level of under-lying agreement between the Scottish government and local government on councils’ key roles in service provision. | In a retreat from the 2007 Concordat, a council tax freeze was imposed by the SNP government from 2007 to 2018. And yet local authorities are still set many targets by the Edinburgh government, and are expected to use resources determined by the centre to achieve goals set by the centre. |

| The importance of Community Planning Partnerships (CPPs), with local government at its heart, is well accepted - together with greater community empowerment in the formulation and implementation of public policy. | Local authorities have faced persistently low turnouts in local elections. This diminishes the authority of local councillors. The large wards required for PR voting in multi-member seats also weaken links to smaller localities. |

| A commitment to prioritising reducing inequalities in CPPs enjoys multi-party support. The Scottish Conservatives appear to accept this, or at least have chosen not to strenuously oppose it. | National politics also intrudes a lot into local campaigning - exemplified by the Conservatives’ emphasis on opposing an independence referendum (wholly outside the competence of local government) in the 2017 local elections. |

| Past problems of local government corruption in one-party areas have generally lessened in recent years. |

| Future opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| If ‘community planning’ can be made to work well, services could potentially be improved, and duplications or conflicts of service provision avoided. | Further financial cutbacks seem likely, but expectations for service delivery from the public and the Scottish Government are not diminishing. Addressing these expectations is likely to become increasingly difficult, given continuing austerity. |

| Potentially, Brexit processes for repatriating policy responsibilities might boost local councils’ roles, if recentralisation in the Edinburgh or UK governments can be avoided. | Austerity might tighten further in the run-up to and aftermath of a second referendum where Scotland votes to leave the UK. |

| Despite some greater consensus than in England (see ‘Strengths’ section), this stance does not extend to prioritising the need for action around agreed principles. Different government tiers and CPP agencies still clash on identifying how to put prevention, engagement, collaboration and efficiency into practice so as to reduce inequalities. | |

| The Brexit process and the second referendum controversy may weaken Scottish economic growth. Brexit may potentially accentuate the centralization of power in Scottish or UK central government. Independence for Scotland might lead to a squeeze on councils’ resources. |

Local government finances

The dependence of local authorities for Scottish central government financial support undermines council’s autonomy. The 2007-18 council tax freeze cut their freedom to raise revenues themselves, although central grants to local authorities did at least taken account of lost revenue. In all 57% of local authority funding comes from the Scottish central government.

A Commission on Local Taxation was established by the Scottish Government and Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (CoSLA) with representatives of all parties in Holyrood, except the Conservatives, who boycotted it. The Commission’s remit was limited to domestic taxation (only 17 per cent of net funding) and it reported in December 2015. It concluded that the existing council tax system ‘needs substantial reform’ because ‘some people are paying more than they should’ and that the ‘present Council tax system must end’ (pages 5 and 79). However, the report failed to offer unambiguous recommendations but instead outlined three alternatives:

• a local income tax;

• a reformed Council Tax with changes in charges for banks; and

• a much more progressive property tax.

The absence of a clear consensus weakened the Commission’s impact. In March 2016 the Scottish Government issued proposals for modest reform, involving increasing the ratios of upper bands to average bands. Once again, a consensus on the need for reform failed to translate into a consensus on what to do next.

Chart 2: The sources of Scottish councils’ income

Source: Audit Scotland 2016: 11

Demographic projections also suggest that Scotland’s population will grow by about 9 per cent over the coming quarter century, but changes will affect local authorities differently. Population decline is anticipated in 12 of 32 areas, while the largest increases will occur in Aberdeen, Edinburgh, and Perth and Kinross. All local authorities can anticipate a growing elderly population, though the change will vary in extent from a 47 per cent increase in West Lothian and Shetland, to the smallest anticipated increase in Dundee. Twelve authorities will have an increase in school age populations, with significant increases in Aberdeen and East Lothian (NRS 2014).

Community Planning Partnerships

By law local councils must work with other bodies – public, private and third sector – at local level through Community Planning Partnerships (CPPs) based on local authority areas. The 2011 Christie Commission’s report on the Future Delivery of Public Services provided a set of well-received principles for reforming public services in integrating ways:

- ‘Reforms must aim to empower individuals and communities receiving public services by involving them in the design and delivery of the services they use.

- Public service providers must be required to work much more closely in partnership, to integrate service provision and thus improve the outcomes they achieve.

- We must prioritise expenditure on public services which prevent negative outcomes from arising.

- And our whole system of public services – public, third and private sectors – must become more efficient by reducing duplication and sharing services wherever possible’.

CPPs include representatives from public bodies including Police Scotland; Scottish Fire and Rescue Service; health boards; further and higher education. The Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 requires CPPs to:

• focus on improving outcomes,

• produce local outcome improvement plans (LOIPs)

• identify geographic areas with the poorest outcomes

• prepare and regularly update locality plans based on priorities agreed in the CPP

• expand the list of partners

• achieve a greater focus on tackling inequalities.

Each public sector member of a CPP retains organisational autonomy, and will have its own specific targets and performance management regimes –so that for councils to lead co-operation may be tricky. While CPPs offer an institutional framework within which to collaborate and address complex wicked problems, targets and performance management regimes remain to a large extent silo-based undermining effective coordination.

A major development in collaboration affecting local government has been the integration of health care (run by the NHS) and social care (run by local authorities). The Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014 created a framework within which adult health and social care would be integrated, intended to shift towards a more community-based and preventative approach. New Integrated Authorities (IAs) to coordinate local health and social care have been established.

Some important centralising institutional developments have occurred in recent years. A single, national Scottish Fire and Rescue Service replaced eight services, and Police Scotland replaced eight regional police authorities under legislation passed in 2012. In both cases responsibilities transferred from local government bodies to these new central government bodies in April 2013. A number of controversies have surrounded the establishment of Police Scotland, including relations with local government where critics argued that well-working previous arrangements were disrupted. It remains to be seen how the new Integrated Authorities in health and social care will operate.

Brexit changes and a second independence referendum

The EU has impacted on Scottish local authorities via:

- Euro-regulation imposing unavoidable obligations to implement, enforce and monitor EC legislation;

- European economic integration, which created new opportunities for, and pressures on, local economies; and

- Euro-funds offer potential support for the local economy and for a range of local authority projects.

In the 1990s councils placed most emphasis upon securing EU funding via ‘grantsmanship’, seeing to influence EU decisions in favourable ways and to identify pockets of regional and ‘solidarity’ funding to tap. More recent local authority engagement with the EU focused more on Euro-regulations and the implications of economic integration. Alteration of the UK’s relations with the EU in terms of the four freedoms – goods, capital, services, people – will have significant implications for local councils as part of a complex multi-level system of government, best thought of as akin to a ‘marble cake’ (according to US political scientist Morton Grodzins). Changes of the magnitude envisaged in the Brexit process are likely to reverberate through the system in unintended ways.

However, Scottish local government may also be able to take some advantage from the changing institutional and policy environment. With clear leadership, councils could address aspects of EU membership that have long irritated local communities and authorities, such as procurement policy and perceived cumbersome bureaucratic mechanisms. There may also be opportunities to ensure that as institutional power returns to the UK and Scottish Parliaments, so that the principle of subsidiarity operates to advantage local government.

If and when it happens, a second independence referendum campaign also presents challenges for local government. But in the 2014 vote a campaign for Our Islands, Our Future set out a bold prospectus for island governance. It demonstrated that it is possible for well organised local government interests to insinuate themselves into even such a highly adversarial battleground as the 2014 Scottish independence referendum. The prospect of another independence referendum might offer another opportunity to ensure that the debate is broadened and includes an agenda that includes the role of local government.

Conclusions

In common with government throughout the UK, Scottish councils face many challenges, especially dealing with future uncertainty. The cuts imposed on English local authorities by central government have been greater and have come faster than those north of the border. Yet in some respects Scottish local government can look over the border to see some of the challenges, especially financial challenges, and the variety of the responses that may await them. With increasing pressure and demands for local government services, the limits on authorities’ financial and policy autonomy point to stormy times ahead.

This article gives the views of the author, and not those of the LSE.

James Mitchell directs Edinburgh University’s Academy of Government and holds the chair in Public Policy.

James Mitchell directs Edinburgh University’s Academy of Government and holds the chair in Public Policy.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

In would be illuminating to hear what the author considers to be the ‘austerity policies’ of the current Scottish Government?