Why Prevent has proved a blunt instrument in the fight against terrorism

The Manchester bombing was carried out by a young Briton from the Libyan community. Tahir Abbas asks what this means for the government’s Prevent strategy, which is supposed to stop the radicalisation that can lead to terrorist attacks. Unfortunately, he argues, the causes of radicalisation often lie in wider geopolitical issues and the mental health of young people – things that Prevent, rooted in local monitoring, does not always address.

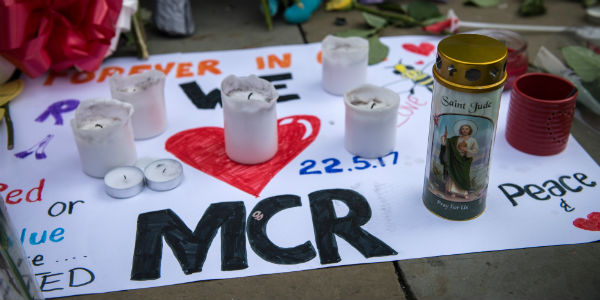

Tributes to victims of the Manchester bombing. Photo: Catholic Church England & Wales via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence

The Libyan community in Manchester is now the focus of reports of radicalisation. Although this not a group that has received much attention from security services in the past, Manchester has the third highest concentration of British Muslims after London and Birmingham. These concentrations tend to be diverse, but sometimes monocultural.

This is an accident of housing policy and labour market inequality, but it also reflects cultural preference in a growing climate of racism and intolerance. When one thinks of these different communities, while ethnicity and culture impact on characterisations, social class, education, housing status and perceptions and identity politics are also crucial considerations.

That the wider British Muslim community, including the Libyans, are utterly appalled by the events in Manchester a few days ago goes without saying. Given the particular nature of this terrorist attack, specifically the brutal reality of children and young people killed at the hands of someone who was himself a very young man, it has affected people deeply. What has also emerged in this particular instance is the mass coming together in response to the challenges caused by terrorist incidents such as this. Mancunians and other people across the UK have united in responding to this attack by deliberately avoiding further division or fomenting hate in any way. There has been a flurry of activity on social media propagating hate, anger and even violence towards Muslim communities. Deluded voices like these tend to homogenise and essentialise a vast religion and its peoples. There also been active resistance of such tropes by people from all backgrounds.

Once the anger and pain of this event begins to dissipate, questions will be asked about how we must completely defeat this hydra. Sadly, however, terrorism has always been around, and it will remain as the tool of anarchists, anti-establishment activists, revolutionaries and even some states. The question of Islamist radicalism in the last two years has centred on acts inspired, instigated or orchestrated by Islamic State, with the Charlie Hebdo shootings in January 2015 the first of a long series of attacks all over Western Europe.

The Manchester attack involved a rather sophisticated device. It appears beyond the means of anyone without some modicum of training or expertise to build it. This suggests there is a greater network at play here, reflected in the fact that the terror threat has been raised from critical to severe. The army is being deployed at key sites across the country as the police concentrate their resources on making further arrests. Questions will be asked, however, about the Prevent strategy, which is intended to stop radicalisation among young people. Surely there a need to refine Prevent, given that after nearly 12 years after its incarnation the terrorist attacks continue. While there is a need to connect the government and the British Muslim communities, the fact that the only dialogue is about radicalisation and deradicalisation invariably creates more challenges than opportunities.

The fight against terrorism is that it does not exist in a vacuum. Wider geopolitical issues are at play. These operate at many different levels and affect how nations do business with each other, share sensitive information or not, and how they cooperate in advance of various strategic objectives. Global issues can transform grievances into revolutionary ideologies, and those ideologies are seen differently around the world. They can ferment in a space where there is disengagement and disintegration, but also where there is a sense of alienation, exclusion and marginalisation. The fact that perpetrators involved in acts of extremist violence frequently suffer from mental illness suggests a wider social, cultural and political malaise affecting young people of all backgrounds. The psychological issues, again, do not exist in a vacuum, as they are a function of lived experiences.

The question is not whether there is the need for more Prevent or less Prevent – in spite of the fact that it is an ongoing process of learning and development. The issue is more about the ways in which the local and global intersect. These concerns, however, are structural and therefore take a long time to shift. The power of Prevent to disengage young people who might be on the path towards radicalisation is related to wider geopolitical issues in the Middle East. Crucially, it is also affected by local area dynamics in relation to community development, and questions of identity, belonging and citizenship.

Some of the opportunities for change, therefore, are very much in the hands of government policy. Mental health issues affecting young radical Islamists are not dissimilar to those affecting other young people in Britain. Public policies have led to widening social divisions, and decoupled the thinking about diversity and difference from notions of multiculturalism. A belief in universal equality has faded. These tensions also affect wider counterterrorism issues that must not be separated from overall thinking.

The question of the long-term objectives in relation to fighting terrorism is an important one. These questions have not changed since the Tube and bus bombings in 2005. Since then, the UK government has had 12 years and extensive resources to research, determine solutions and ensure that terrorism, and the violent extremism that leads to it, is eradicated.

Fighting terrorism is a multi-pronged battle. The UK government is attempting to tackle it on various fronts, but the problems continue to re-emerge. This does not mean a radical departure from existing practices. It does, however, spell the need for more joined-up thinking and a better understanding of the links between the local and global. A failure to appreciate the holistic nature of how terrorism works, in particular global radical Islamism, can lead to culs-de sac and reactionary, regressive strategies in counter-terrrorism policymaking. That will lead to more terrorist attacks, not fewer. After the events in Manchester, we need to not simply do more of the same, but to get it absolutely right.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It is an edited version of a post on Tahir Abbas’ blog.

Professor Tahir Abbas FRSA is Visiting Senior Fellow at the Department of Government at the London School of Economics, and author of Contemporary Turkey in Conflict: Ethnicity, Islam and Politics (Edinburgh University Press, December 2016).

Professor Tahir Abbas FRSA is Visiting Senior Fellow at the Department of Government at the London School of Economics, and author of Contemporary Turkey in Conflict: Ethnicity, Islam and Politics (Edinburgh University Press, December 2016).

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here: democraticaudit.com/2017/05/26/why-prevent-has-proved-a-blunt-instrument-in-the-fight-against-terrorism/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Informations here: democraticaudit.com/2017/05/26/why-prevent-has-proved-a-blunt-instrument-in-the-fight-against-terrorism/ […]

[…] This article was originally published by our sister site, Democratic Audit. It is an edited version of a post on Tahir Abbas’ blog. The article gives the views of […]