The “empty centre”: how voters’ views have polarised since 2015

Following up from his 2015 analysis on the economic and cultural positions of party supporters in England, Jonathan Wheatley uses 2017 data and finds that party supporters have become far more polarised – leaving a gap in the middle, occupied possibly by large numbers of undecided voters. It is this ’empty centre’ on the economic and cultural scales that Labour and the Conservatives will need to win over.

Antarctica’s Pine Island glacier began to break up in 2011. Photo: Nasa Goddard Space Flight Center via a CC BY 2.0 licence

In a blog I wrote after the 2015 general election, I described how political opinion is too complex to be described exclusively in terms of “left” and “right”. I argued that if you are “left” or “right” in economic terms, this does not necessarily mean that you will be in the same camp when it comes to issues of culture and identity. I proposed that we should consider two dimensions of political opinion.

The first is an economic dimension about whether you prefer pro-free market economic policies on the one hand, or redistribution of wealth and a greater role of the state in the economy on the other. The second is a cultural dimension, which I referred to as communitarian-cosmopolitan, but which other commentators have described as “open versus closed”. It concerns the relationship of your community with the outside world, draws on issues such as EU membership and immigration, and, to coin David Goodhart’s terms, is about whether you are “from Anywhere” or “from Somewhere”. Since the UK voted to leave the European Union and Donald Trump won the US elections last year, both political analysts and journalists have been discussing this dimension. Immediately after Brexit, the Economist published a leader entitled “The new political divide” in which the editors suggested that the “open against closed” now divide matters more than that between left and right.

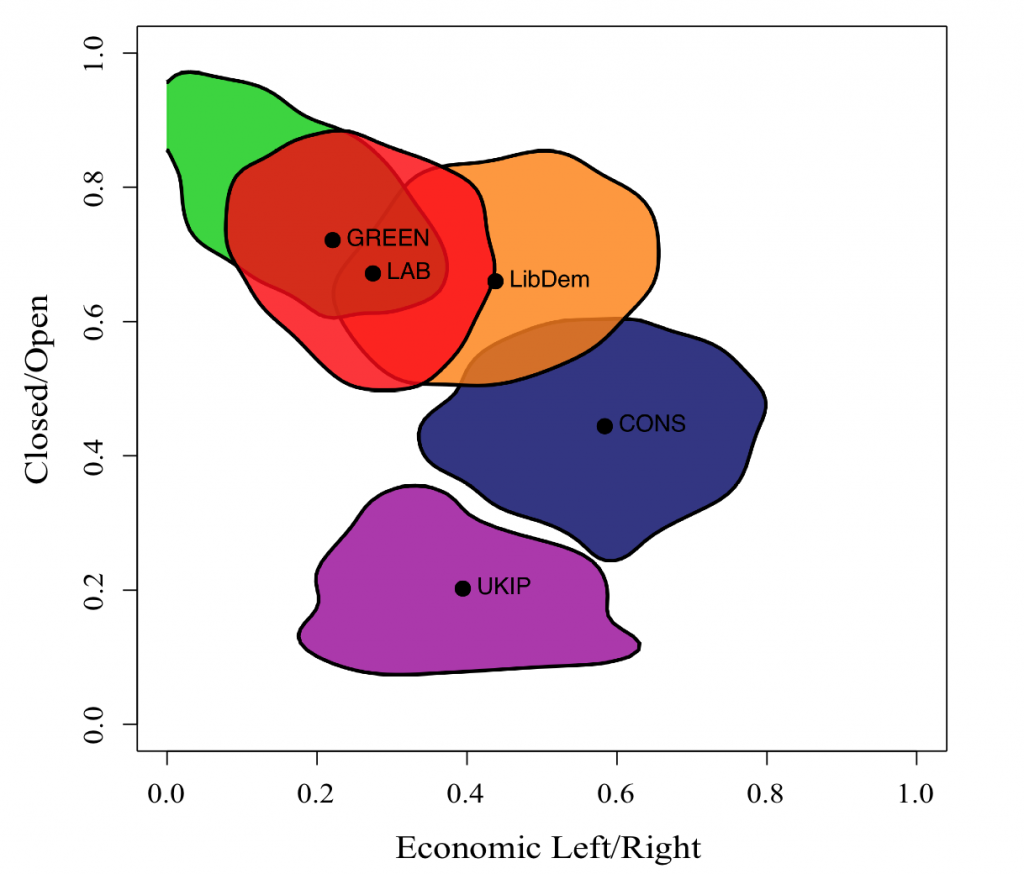

In the earlier blog, I used the responses of users of a Voting Advice Application called WhoGetsMyVoteUK to a battery of policy items first to identify the issues that formed part of these dimensions (using a dimension reduction technique called Mokken Scale Analysis) and then to map the positions of the supporters of five parties (Conservatives, Labour, Liberal Democrats, UKIP and Greens) with respect to them. Party supporters were defined as those who a) listed a given party as being closest to them and b) said that they would vote for that same party. Their positions on the map are calculated from their opinions on relevant issues. The map (below) shows where they stood in the run-up to the May 2015 elections. The lines around the bubbles are “contour lines” that enclose 50% of the party’s supporters. We see that in 2015, the parties had very distinct positions on both dimensions, but at the same time there was a significant degree of overlap between the different groups of party supporters.

Diagram 1 shows the mean positions of each party’s supporters in 2015.

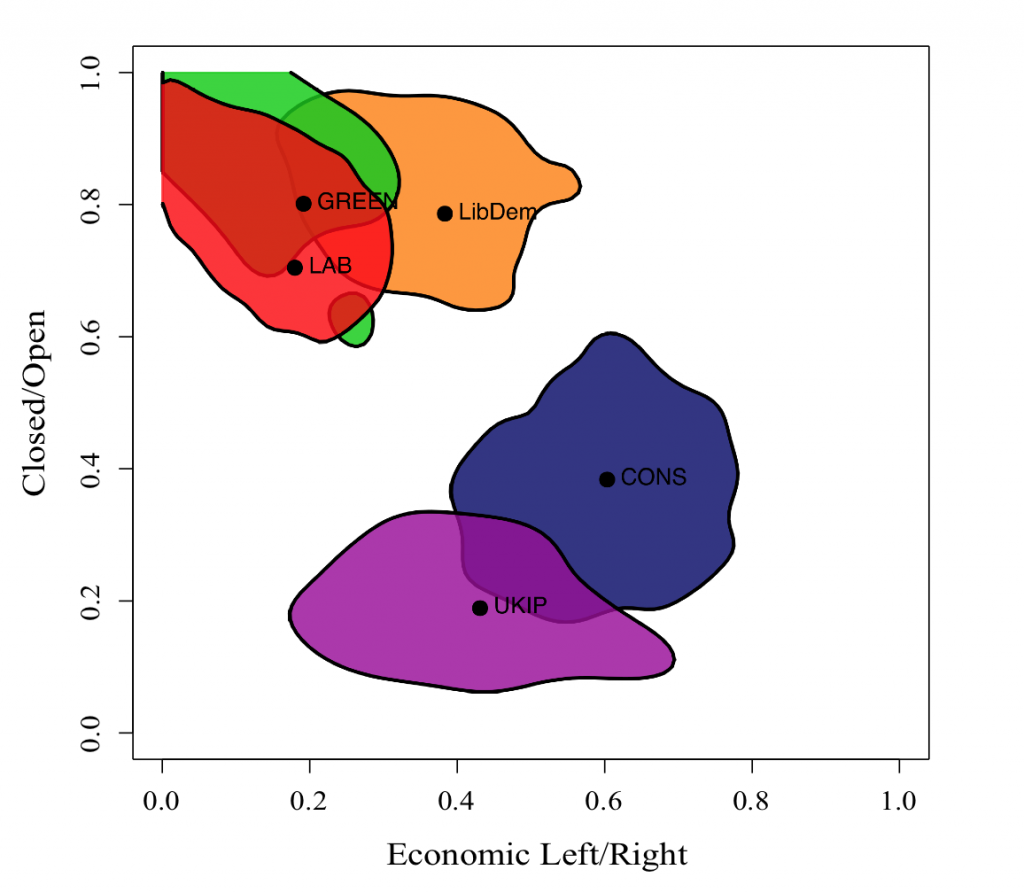

In the run-up to the forthcoming general elections, an updated version of WhoGetsMyVoteUK has been launched, and I am already able to explore the responses of the first 23,000 or so users to have taken part. As before, I look only at English parties as the app asked rather different questions in Scotland and Wales and the data from these two nations cannot be directly compared with the English data. Performing exactly the same analysis as I did for the 2015 data, I identify very much the same dimensional structure as before with issues relating to redistribution of wealth, health sector privatisation and university tuition fees forming part of the (economic) left-right dimension and issues involving the future relationship with the EU, immigration, foreign aid and LGBT-inclusive sex education making up the (cultural) “closed versus open” dimension. Far more dramatically, however, we see that the positions of party supporters with respect to these dimensions have changed significantly.

Diagram 2 shows the mean positions of each party’s supporters in 2017.

It is better not to focus on the actual positions of party supporters in the map as they depend on rather different opinion items compared with the 2015 version and are therefore measured in a different way. Looking instead at their relative positions, we see that party supporters have become far more polarised, especially with respect to the closed versus open dimension, but also to a certain extent with respect to the left-right dimension as well. Labour, Green and even Liberal Democrat supporters are concentrated near the “left-open” corner while Conservative and UKIP supporters are also joined in an embrace and are located towards the “closed” pole of the map. At the same time there is a wide gap in the middle that is not occupied by any party’s supporters. This, perhaps, reflects the legacy of last year’s referendum campaign, which may have led to a polarisation of preferences.

In reality, the middle is not empty and, given the recent volatility in the opinion polls, most likely contains large numbers of undecided voters. It is these that all parties, and especially the two main parties, will need to win over. For Labour, the dilemma is that they need to draw from two very distinctive support bases. On the one hand, there are the traditional Labour heartlands of the North and the Midlands, whose voters often take a “closed” position on the cultural dimension, and may have voted for Brexit or even toyed with UKIP in 2015. On the other are young cosmopolitan “open” voters, typically from London or the Home Counties, who may also consider the Lib Dems or the Greens. These two support bases seem to have moved further apart after last June’s referendum and are hard to accommodate in a single “tent”. From the evidence presented here and from opinion poll evidence, the latter group seem to have swung clearly behind Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, while the former remain open to persuasion.

Both during the election campaign and previously, Theresa May has consciously attempted to target “closed” economic leftists. In terms of the cultural dimension, the famous comment in her speech at last year’s Conservative Party Conference that “if you believe you’re a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere” represented a clear break from David Cameron’s more cosmopolitan outlook. Moreover, the Tories’ (at least superficially) economically leftist proposals during the election campaign to increase the living wage and statutory rights for family care and training, and to strengthen labour laws, represents a clear attempt at appealing to a more economically left-wing audience. However, it would seem that the appeal to this group has met with only partial success and has yet to be transformed into “hard” Conservative votes. While Jeremy Corbyn has been accused of aiming his appeal exclusively at already convinced leftists, by hyping up their focus on Brexit and adopting a more confrontational rhetoric towards European leaders, Theresa May’s Tories risk falling into the same trap of “preaching to the converted”.

It is sometimes said that elections are won from the centre ground. As former Shadow Secretary of State for Education Tristram Hunt pointed out in a recent article in New Statesman, perhaps this does not only apply to the centre in conventional left versus right terms, but also in terms of “open” versus “closed”.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It first appeared at LSE British Politics and Policy.

Jonathan Wheatley is Lecturer in Comparative Politics at Oxford Brookes University.

Jonathan Wheatley is Lecturer in Comparative Politics at Oxford Brookes University.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] Source […]