Audit 2017: How democratic is local government in Northern Ireland?

Local authorities play key roles in the devolved government of Northern Ireland, as expressions of communities that were in the past highly polarised on religious and political lines. They are also the only other source of elected legitimacy to the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive, and can act as checks and balances on the domestic concentration of power. As part of the 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, James Pow explores how democratically local councils have operated in difficult conditions.

Detail from the Belfast city crest on a carpet in the City Hall. Photo: Irish Fireside via a CC BY 2.0 licence

This article was published as part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy. We have now published: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit with LSE Press, available in all ebook formats. You can download the whole book for free, and individual chapters, including a fully revised version of this article.

What does democracy require of Northern Ireland’s local governments?

- Local governments should engage the wide participation of local citizens in their governance via voting in regular elections, and an open interest group and local consultation process.

- Local voting systems should accurately convert parties’ vote shares into seats on councils, and should be open to new parties entering into competition.

- As far as possible, consistent with the need for efficient scales of operation, local government areas and institutions should provide an effective expression of local and community identities that are important in civil society (and not just in administrative terms).

- Local governments should be genuinely independent centres of decision-making, with sufficient own financial revenues and policy autonomy to be able to make meaningful choices on behalf of their citizens.

- Given the special history of Northern Ireland, deliberative policy-making has a particularly key role in building local political harmony and understanding of multiple viewpoints and interests.

- Local governments are typically subject to some supervision on key aspects of their conduct and policies by a higher tier of government. But they should enjoy a degree of constitutional protection (or ‘entrenchment’) for key roles, and an assurance that cannot simply be abolished, bypassed or fully programmed by their supervisory tier of government

- The principle of subsidiarity says that policy issues that can be effectively handled in decentralised ways should be allocated to the lowest tier of government, closest to citizens.

Recent developments

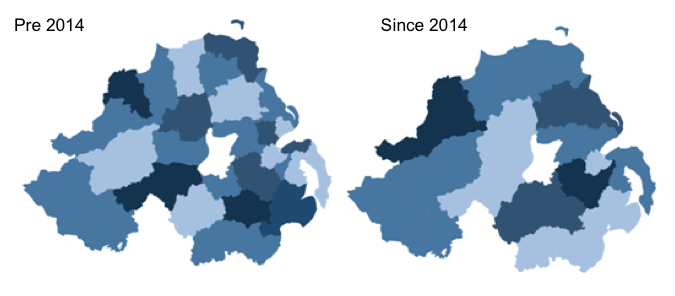

Local government areas and structures recently went through the biggest shake-up to its structure and organisation since the early 1970s. A major 2005 review initially recommended that 26 local government districts be radically streamlined into just seven ‘super-councils’. After devolution was restored at Stormont in 2007, the power-sharing administration ultimately made a compromise to reduce the number of districts, but only to 11. Of these, six have predominantly unionist electorates, four have predominantly nationalist electorates, and one, Belfast City, is relatively balanced.

The first elections to the revised council districts took place in May 2014; the transfer of power from outgoing administrations was complete within a year. The reformed councils removed many ‘legacy’ features, and so provided fresh opportunities for citizens to re-engage with local government politics. A key reform hope was also that councils themselves can enhance the democratic quality of their decision-making processes. Their average size is over 171,000 people, far larger than their predecessors, with a range from 339,000 in Belfast City to 115,000 in rural Fermanagh and Omagh.

Figure 1: How structural reforms changed local government districts

Northern Ireland councils have fewer responsibilities than councils elsewhere in the UK, partly reflect both the province’s relatively small population and the deeply divided nature of its society. The Housing Executive is Northern Ireland’s single public housing authority, set up in 1971 in the wake of discriminatory housing allocations by district councils. It is a quasi-government agency (technically an executive non-departmental public body or NDPB). It is operationally independent of the Northern Ireland Executive, but accountable to the Minister for Communities. Transport NI is the region’s sole road authority. The Education Authority (EA) is responsible for all educational and library services. And the provision of social care is overseen by six trusts. These public bodies are each accountable to the Northern Ireland Executive, but not to local councils.

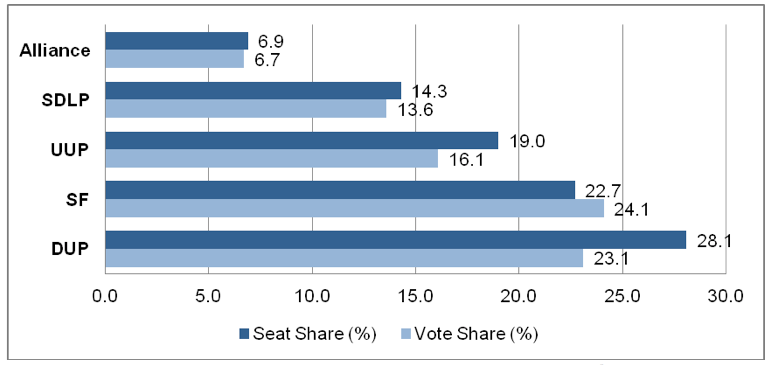

Proportional elections in the new councils

Apart from general elections for the Westminster Parliament, all elections in Northern Ireland are conducted using the Single Transferable Vote electoral system (known as PR-STV in Northern Ireland). The most recent council elections in 2014 using STV generated reasonably proportional results – that is, the number of first preferences received by each of the five main parties broadly corresponded to their total share of seats, to within a handful of percentage points. The results produce a deviation of proportionality (DV) score of 11.1% This is much lower than average scores for Britain’s Westminster elections, using plurality rule voting.

Figure 2: How the main parties’ shares of votes compared to their share of seats in the 2014 council elections

Notes: DUP: Democratic Unionist Party; SF: Sinn Féin; UUP: United Unionist Party; SDLP: Social Democratic and Labour Party.

However, STV elections are preferential (i.e. voters can number multiple choices of candidates 1, 2, 3 etc. in an order they choose) as well as proportional. So effective vote management and how voters transfer preferences to other parties can influence the results. In 2014 a fragmented distribution of first preference votes across smaller unionist parties disrupted their chances of winning seats. Once these early preferences were eliminated in the counting process, then second or later preferences from these parties’ voters were transferred to their next preferences. Figure 2 shows that the DUP gathered the most of these later vote transfers, thus apparently ending up ‘over-represented’ against their first preference votes. So it would be too simplistic to say that voters who supported smaller parties are left unrepresented – they may not be represented by their first preference party, but by one lower but still positive in their preferences.

Northern Ireland voters historically participate more in local government elections than those elsewhere across the UK. In 2014 over 51 percent of registered voters cast a ballot. This was none the less the lowest level of turnout recorded in a local government contest in Northern Ireland. But it still compares favourably to England’s 36% on the same day. The continued predominance of ethno-national voting in Northern Ireland (at all levels) encourages voters from rival political/religious groups to try and maximise unionist and nationalist representation respectively. Participation is also encouraged by holding council elections concurrently. All other council elections over the last two decades have occurred on the same day as either Westminster or Assembly elections. But in 2014 contests the other elections were for only the European Parliament.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Local authorities across the UK have no entrenched constitutional protections. However, following their protracted and controversial creation process, Northern Ireland councils have perhaps more protection from further changes coming from the tier above them. | Despite a proportional electoral system, important groups are under-represented. Only a quarter of councillors are women, lower than the percentage of women in the Northern Ireland Assembly. Citizens who identify as neither nationalist nor unionist may also not be adequately represented. |

| The PR-STV electoral system is broadly proportional. The preferential voting aspect of the system minimises the likelihood of wasted votes. | Relatively high levels of turnout may partly reflect the continuing salience of sectarian loyalties (linked to ethno-national political competition) rather than a high level of engagement with municipal issues per se. |

| Participation levels in local government elections are relatively high, facilitated by a tradition of holding them concurrently with elections to other levels of government. | Under STV you cannot easily hold by-elections, since the process relies on multi-member seats. Instead the political party holding the seat is allowed to nominate (co-opt in) a new person when councillor vacancies arise. This gives parties a lot of power, since one in ten councillors across Northern Ireland has been co-opted. Between May 2014 and April 2017, 42 co-options have been made across Northern Ireland, at least one on every council. The highest number has been made on Belfast City Council, where 18.3% of incumbent councillors are unelected. |

| Councillors are no longer permitted to hold multiple mandates. The shift away from ‘double-jobbing’ is designed to promote clearer electoral accountabilities. | Despite recent reforms of local government, there has been no effort to introduce innovative mechanisms of public consultation, such as citizen juries or planning cells. |

| The transfer of local planning powers to councils may help to promote transparency in and engagement with local decision-making. |

| Future opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| The transfer of some additional powers to local government level may increase support for additional democratic reforms, such as developing better or new forms of public consultation. Gaining these additional powers could help focus councillors’ minds away from controversial issues of symbolism towards more substantive policy decisions that lack any obvious ethno-national connection. | The recent election to the Northern Ireland Assembly (2 March 2017) was preceded by a bitter campaign, showing an increasing salience of the ethno-national dimension. This may trigger regressive polarising motions and debates in local councils in reaction. As the dispute over the flying of the flag at Belfast City Hall demonstrated, decisions on sensitive issues – even if they are the result of a democratic procedure – can stir fervent opposition beyond the council chamber. |

| In the event that the fragile power-sharing administration fails to re-start (or collapses) at Stormont, representatives from the local government level will play a greater role in mitigating any democratic deficit. | If direct rule has to be restored, because Stormont cannot, the oversight responsibilities for three key quasi-government agencies with urban roles - the Housing Executive, Education Authority and Transport NI - will transfer to Westminster. This would add further distance between citizens and accountability mechanisms over major agencies of local/regional government. |

| There has been some trend towards fostering local economic development at least in bi-partisan ways. | There is still not a consensus on all the key roles played by local governments across the main parties, and sensitive sectarian issues can arise in many applied policy contexts. |

Still ‘tribal’ elections?

Just over half (52%) of councillors elected in 2014 were elected to one of the main unionist parties, and 37% to one of the main nationalist parties. However, cross-sectional evidence from the annual Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey has consistently found since 2006 that at least 40% of citizens (a plurality) identify as neither nationalist nor unionist. As in higher levels of government, this group of voters appears to be systematically under-represented under the existing party system.

The reformed structures of local government have not been accompanied by a significant improvement to women’s representation. A quarter of councillors elected in 2014 were women, up just 1.6 percentage points on 2011. The aggregate level masks variation across the new districts. Women are a third of the members of Belfast City Council, but just one sixth of members on North Down and Ards Council.

Until new legislation prohibiting dual mandates came into effect in 2016, several incumbent members of the Northern Ireland Assembly (MLAs) were also elected to local government in 2014. The new rules now prevent the democratically dubious practice of ‘double-jobbing’. But the one-off vacancies left by MLAs vacating their seats were filled by ‘co-option’ (see Weaknesses, above) giving political parties, not voters, the exclusive right to nominate a successor.

Some council planning powers, but not more transparency

As part of the reorganisation of local government, the 11 new councils gained some additional powers from the Northern Ireland Executive. Most notably, decisions on the majority of planning applications and urban regeneration now rest at the level of local government, not the Department for Infrastructure. This transfer of power mandated by the 2011 Planning Act (Northern Ireland) has a democratic objective:

‘[The change] will make planning more locally accountable, giving local politicians the opportunity to shape the areas within which they are elected. Decision making processes will be improved by bringing an enhanced understanding of the needs and aspirations of local communities’.

A 2011 report on public and stakeholder opinion of the Northern Ireland planning system found it to be poorly regarded by citizens, developers, and planners themselves. Citizens tended to see the relationship between planners and developers as too close, while developers tended to see the process as too inefficient. The reformed planning system remains in its infancy, so it is too early to tell whether or not the public and stakeholders perceive the revised system as more legitimate than its predecessor. At this stage, there is no evidence that the new councils have embraced global democratic innovations in planning, such as utilising citizen juries or deliberative planning cells. Regardless of their satisfaction with the new system, citizens and stakeholders may at least more clearly identify council representatives as accountable for decision-making.

Budgets remain constrained

As in Scotland and Wales, local councils receive most of their funding from the next tier up, here the Northern Ireland Executive. However, most of this money in turn comes from the UK exchequer under the Barnett formula, which maintains a broad parity with England public spending. As a result of UK-level austerity policies, funding for Northern Ireland local authorities has declined appreciably.

Decisions are sometimes contested

Given the carefully limited powers of local government, it may be somewhat surprising that council decisions still have the potential to spark controversy and raise fundamental questions over democratic legitimacy. But symbolism is still important. In December 2012 Belfast City Council voted to restrict the number of days that the Union Flag could be flown from City Hall. Nationalist councillors initially proposed a motion that would discontinue the flying of the flag altogether, but lacked a majority to carry it. The cross-community Alliance Party successfully proposed an amendment that would see the flag flying on 18 designated days during the year, in line with official government guidelines. In the end 29 councillors supported the amendment, but all 21 unionist councillors voted against.

The decision prompted street protests across Northern Ireland, some of which turned violent. Loyalists saw the decision as an attack on their British identity. A public consultation conducted as part of an Equality Impact Assessment suggested that a large number of citizens would be offended by any change to the council’s policy. The Chief Constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland blamed loyalist paramilitaries for orchestrating disorder. The Alliance Party, holding the balance of power on Belfast City Council, was a key target. Some of its councillors’ homes were attacked, one of its offices was set alight and destroyed, and its sole MP (Naomi Long) received a death threat. Violence eventually dissipated, but the council’s decision stood. Small, peaceful protests have been held outside Belfast City Hall every Saturday afternoon ever since.

This case study shows how a democratic decision, made after a major public consultation, can still face widespread disorder in a politically polarised society like Northern Ireland. Even if a decision is made following consultation and in line with majority views, the decision itself may lack sufficient buy-in on a cross-community basis. Each of the 11 new reorganised councils has made individual decisions on flag-flying policies. Some decisions have attracted protests, but none of the intensity or scale of those seen in Belfast in 2012.

Northern Ireland politics in flux

At the time of writing (June 2017), Northern Ireland lacks a devolved power-sharing government. After a snap Assembly election on 2 March and a highly acrimonious campaign, the two largest parties (the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Féin) failed to reach agreement for many months on the formation of a new administration. If direct rule from Westminster has to be restored, then the British government assumes responsibility for matters devolved under the Northern Ireland Act (1998), diminishing potential oversight over public services from Northern Ireland voters, especially housing, education and road maintenance (see above). Connections with local council services might suffer too, since the vast majority of Westminster MPs lack experience in, or any strong incentive to understand, local governance in Northern Ireland.

The June 2017 general election further complicated matters by creating a further polarisation of the province’s Westminster MPs between just the DUP and Sinn Féin, and by bringing the DUP into supporting the Conservative’s minority government, potentially jeopardising the UK government’s ability to be seen as impartial arbiters in Northern Ireland politics.

Conclusion

Local government in Northern Ireland apparently meets many democratic criteria to an encouraging extent, especially in the electoral legitimacy of councillors, high turnouts at elections, and a continuing ability to engage citizens’ political interest. However, the continued predominance of the ethno-national dimension at all levels of Northern Ireland politics casts doubt on the extent to which citizens engage with the substantive issues of local government, impairs the deliberative and consensual quality of their decision processes, and has caused democratically-controlled local powers to be kept very minimal. Still, at the time of writing, councillors have for several months been the only elected officials making public policy decisions in Northern Ireland. Despite their comparatively narrow remit they have maintained some reality behind devolved powers across the region.

This post does not represent the views of the London School of Economics.

James Pow is a postgraduate research student at the School of Politics, International Studies and Philosophy, Queen’s University Belfast.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Interesting but factually incorrect in that the biggest difference is virtual absence of austerity at local government level as unlike rest of UK most income is set and raised locally via rates and dependency on stormont or westminster much less. Also the absence of manifesto based politics and majoritarian administration means the conduct of business is less transparent and arguably hinders development of genuinely local innovation.