Audit 2017: How democratic is the devolved government of London?

Devolved government in London – focusing on the executive Mayor and Greater London Assembly – started as a radical innovation in 2000. Its generally successful development has sparked a slow, ‘organic’ spread of executive Mayors to other English cities and conurbations. As part of the 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Andrew Blick and Patrick Dunleavy explore how democratically and effectively the two London institutions have performed.

Photo: Lena Vasiljeva via a CC-BY NC 2.0 licence

This article was published as part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy. We have now published: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit with LSE Press, available in all ebook formats. You can download the whole book for free, and individual chapters, including a fully revised version of this article.

What does democracy require of London’s devolved government?

- Elected politicians should normally maintain full public control of devolved government and public services. In the London system this means there should be accountable and transparent government exercised by the Mayor. The Assembly should ensure close scrutiny of the executive, and allow other parties to articulate reasoned opposition via its proceedings.

- TheGreater London Authority (GLA, comprised of the Mayor and Assembly acting together) should be a critically important focus of London-wide political debate, particularly (but not limited to) issues of devolved competence, articulating ‘public opinion’ in ways that provide useful guidance to decision-makers in making complex policy choices.

- Individually and collectively Assembly members should seek to uncover and publicise issues of public concern and citizens’ grievances, giving effective representation both to majority and minority views, and showing a consensus regard for the public interest.

- The London Mayor as executive should govern responsively, prioritising the public interest and reflecting public opinion in the capital.

- The GLA administration should be realistically and reliably funded, with resources so scaled that it could carry out its functions well, so long as it is efficiently and effectively run.

- The GLA should be a stable part of the UK’s constitutional set-up, with considerable protection against ill-considered or partisan interventions in how it works originating from central government or Parliament.

The Greater London Authority (GLA) was established after a 1998 referendum, which saw Londoners endorse – by 72 per cent on a 34 per cent turnout – a new strategic government for the capital proposed by the Blair government. It consists primarily of a Mayor and Assembly, each elected by voters across London every four years. The mayor controls the GLA’s executive powers, which cover strategic and London-wide functions – especially public transport and roads, policing via the Metropolitan Police, fire services, and strategic planning and economic development. The small (25 member) Assembly is elected using a form of proportional representation. It scrutinises the mayor’s policies, budgets and conduct in office, and allows different parties to develop and advocate for varying policy agendas. All other local government services are run by 32 London boroughs, with which the GLA must co-operate to achieve many goals (see below).

The GLA was deliberately set up by Tony Blair to be a slim top-tier body, with a strong mayor and a weak Assembly, whose members would be forced to focus on London-wide issues, and not local ones. The Assembly’s only clear powers are that it can reject or amend the strategies or the budget that the mayor proposes. However, in both cases, a two-thirds majority in the Assembly is required to replace the original proposal, which is very difficult to achieve. So in practical terms the Assembly can only scrutinise the activities of the Mayor through a range of committees. It can also hold public hearings with the key post holders appointed by the Mayor, but lacks the power to block their appointment.

Recent developments

In the fourth round of the mayoral elections in 2016, using the Supplementary Vote election system which requires candidates to gain a majority of eligible votes, Labour’s Sadiq Khan won 58% support in the run-off stage to convincingly beat the Tory candidate, Zac Goldsmith. He succeeded Boris Johnson, who had served eight years as London mayor. Khan’s manifesto priorities were to build more homes (of which half would have to be ‘genuinely affordable’), freeze transport costs and tackle gangs and knife crime. In an effort to reduce air pollution, the mayor also announced a ‘T-charge’ (a levy on more polluting vehicles) to apply within London’s congestion charging zone from late 2017.

The Assembly election uses a form of Additional Member System (AMS), with 14 local constituency seats (spanning two or three London boroughs) with winners elected by ‘first past the post’ (or plurality rule) voting. However, voters then have a second vote for 11 London-wide seats, which are distributed to parties so as to make their total seats shares align with their vote shares. In 2016 Labour and the Conservatives won all the local seats between them, and gained top-up seats as well – ending up with 12 and 8 total seats respectively. This continued a pattern that stretches back over many elections for the top two parties to dominate the capital’s politics. The Greens (2 seats), Liberal Democrats (1 seat) and UKIP (2 seats) had more limited success at the top-up seat stage.

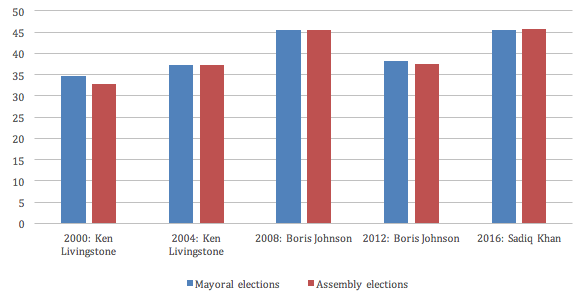

Turnout in 2016 rose to 45 per cent, matching the 2008 peak when Boris Johnson was first elected.

Chart 1: The percentage turnout in the five London mayoral and Assembly elections since 2000

In the June 2016 Brexit referendum just under 60 per cent of Londoners voted to remain in the EU, reflecting the city’s more youthful population, and perhaps factors such as the importance of EU workers for many key industries and services, and the capital’s stronger dependence on Europe for trade and markets. Efforts by Sadiq Kahn to influence UK policy towards a ‘softer’ Brexit (backed by the vast majority of bigger London businesses) have so far been decisively rejected by Whitehall.

Finally, the GLA’s policy roles and competencies sprang into far greater prominence in the spring and summer of 2017 following three terrorist attacks in central London (two on iconic bridges), plus the catastrophic fire in the municipal Grenfell Tower block. For homeland security it became clear that protecting citizens from vehicular assaults would require a far-reaching re-assessment of roadside barriers (belatedly introduced on London bridges) and other ‘passive’ measures. This will require much greater liaison between the Metropolitan Police and GLA and borough highway authorities. The fire tragedy also attracted criticism for the initial response by the small Kensington and Chelsea borough and by Whitehall departments; the possible under-funding and under-management of public housing that had gone before; and issues about the adequacy of fire regulations policed by the GLA-controlled fire service. There are implications here for the two-tier local governance of London, with the mayor and GLA likely to emerge with stronger abilities to guide how boroughs carry out some functions.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Mayoral elections have proved genuinely competitive, with the winners being an independent candidate (Ken Livingstone in 2000), Labour candidates (Livingstone in 2004 and Sadiq Khan in 2016) and a Conservative candidate (Boris Johnson in 2008 and 2012). In each round the top two candidates have been very easily identified by voters. Turnout has been substantial for new bodies, recently established, and has risen overall. | Theoretically any mayor whose party holds 9 or more votes in the 25 member Assembly can never be defeated, and so need take no notice of its views. In practice, mayors have wanted to be seen as performing well in scrutiny meetings and as acting with majority support in the Assembly. But these more subtle means of Assembly influence are not widely known, and its role is not seen as very important by most London citizens. By contrast, the mayor is seen as very powerful. |

| The intense interest generated by these contests, and the strong legitimacy produced by winning clear majorities under the SV voting system, have made the London Mayor a key politician not just in London, but across the UK and internationally. Each of the Mayors has been able to represent London internally and externally, wielding both hard power (via extensive policy reach) and soft power (via media prominence and a clear mandate). | In the mayoral election, voters have first and second preference choices. If no one wins over 50% support on first preferences, then the top two candidates stay in the race and all others are eliminated. The second preferences ballots cast by voters supporting for eliminated candidates are examined, and any 2nd votes for the candidates still in the race are added to their piles. However, if voters cast both preferences for eliminated candidates, these are not ‘eligible’ and do not influence the result. |

| Since it was established, the GLA has become a firmly established fixture of UK governance and its powers have expanded over time. For the foreseeable future, it is difficult to imagine any UK government seeking to abolish it, as Margaret Thatcher did with its predecessor (the Greater London Council) in 1986. | Despite the high level of public attention around mayoral elections, turnout in elections has fluctuated between the low 30s and mid 40s (see Chart 1 above) – levels found in other local elections, and well below those in the devolved countries. |

| Mayors have made creative use of the powers they possess, especially in the field of transport. The congestion charge (introduced by Ken Livingstone) is a good example of innovation in this area. Their ‘soft power’ advocacy has also been influential, for instance in encouraging take up of the London Living Wage. | Smaller parties, those which win less than 5% of the London-wide votes for the Assembly, are debarred from winning any seats through a rule inserted to discourage undue party fragmentation under PR. The larger parties gain from this. |

| The AMS election system for the Assembly has led to a greater diversity of parties being represented there, reflecting to a good extent the diversity of views within the huge London electorate. | When parties win top-up Assembly seats, the successful candidates are chosen in order from a ‘closed’ party list, which voters cannot influence. |

| The supplementary vote system used for the mayoral elections creates the opportunity for a larger proportion of voters both to choose their favoured candidates and have more influence on the outcome than they would do under a simple plurality voting system. | Theoretically, in a very tight race, the SV system used for the Mayoral election could lead to a candidate who came second on first preferences winning at the second round. So far in practice the contest has in fact always been won by the leading candidate in first preferences. |

| The Assembly has 20% ethnic minority members and a generally better gender balance (with women forming 40% of members) than most UK political institutions. However, black and Asian minority ethnic people now form 40% of London’s population, so that much remains to be achieved. | Ten of the 14 Assembly local constituency seats have never changed party control, which may lead to complacency and inertia. |

| Mayors must negotiate many of the policies with Whitehall, or with quasi-government agencies running functions like airports or national railways, or the 32 London boroughs running local services. Success here involves ‘soft’ rather than ‘hard’ power. The seven strategic plans that the Mayor is required to produce rely a lot on others for their implementation - eg, despite strenuous efforts, mayors have made little discernible impact on decisions about London airport capacity. |

| Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|

| The Brexit process has seemingly strengthened Londoners’ sense of the capital as having distinct economic interests. Although exiting the EU may overall harm London’s economy (see threats), the transferring back of powers from Brussels may create new opportunities for repatriated functions to expand the scope and coherence of GLA policy roles. Whitehall ‘overload’ post-Brexit may also increase favourable shifts of responsibilities. | The Brexit process promises to be turbulent and may adversely affect financial services, a key part of London’s economy and tax base. The 2017 Tory manifesto also indicated the government would move large numbers of civil service jobs and some cultural institutions out of London. |

| The mayor may also be able to sustain the domestic momentum it had previously generated towards the extension of GLA’s powers. This push could also capitalise on the wider trend towards greater devolution in the UK. | If tensions between the GLA and the London Boroughs grow, plans to build affordable housing may be hampered. |

| Brexit could be used to justify the argument that London should have independent capacity to respond flexibly to the challenges leaving the EU creates. | The 2017 Conservative election manifesto suddenly proposed to scrap the SV system used for electing the executive mayors in London and other UK cities, replacing it with first past the post. This would tend to wreck the mayor’s legitimacy and in multi-party politics could lead to winners with far less than majority support. Since the voting system was part of a package approved by a London referendum in 1998, it is unclear that Westminster can make such a change without another referendum. The Tories lost the election, with the manifesto being rated disastrous, so that no action may follow. |

| A Conservative government could be reluctant to transfer significant new powers to or otherwise cooperate with the now Labour-dominated GLA. | |

| Further devolution to England may be concentrated on cities or regions that did not previously have it, so that London might lose out. | |

| The Assembly’s limited role may become harder to justify in future, given its relative insignificance in constitutional and governmental processes. |

How the Authority works

The Greater London Authority was established under the Greater London Authority Act 1999, with the inaugural elections to the Greater London Assembly and for the office of Mayor held in May 2000. The introduction of the Authority followed a period, since 1986 and the abolition of the Greater London Council, in which there had been no directly elected tier of governance for London. The Authority is often regarded as being devolved rather than local-level government, though it does not possess powers as extensive as those attached to the devolved institutions in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland that were also established at around the same time. In particular, the Authority does not have the full primary law-making powers that are attached to those devolved institutions.

Other areas in which the mayor has the power to operate are policing, economic development, housing and regeneration. These powers are exercised via four functional bodies: Transport for London; GLA Land and Property; the London Fire and Emergency Planning Authority; and the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime. The Mayor is also required to produce strategies for transport, housing, culture, economic development, health inequalities and spatial development. The Mayor is also able to intervene in some local authority planning decisions. The Authority raises money from council tax precepts; business rates; transport charges; and an infrastructure levy.

Successive Acts of Parliament have expanded the powers of the Authority: the Greater London Authority Act 2007 granted new roles in skills and employment, and housing. The Localism Act 2011 gave the Mayor more land and housing powers; and allowed the Mayor to form Mayoral Development Corporations. The Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011 made the Mayor the Police and Crime Commissioner for London; and the Public Bodies Act 2011 gave the Authority some development powers.

Financial dependency and budgets

Like all local authorities in the UK, the Greater London Authority must legally submit a balanced budget, where its current spending and revenues are equal. As Table 1 shows the scale of GLA operations is vast, with current spending of £11.8 billion. Because of transport receipts the Authority actually generates over 70 per cent of its own resources, but depends on Whitehall for grants of over a fifth of its income, and also has local business rates redistributed away by Whitehall to other poorer authorities. It collects a share of business rates and levies a council tax precept that is collected by the boroughs on its behalf.

Table 1: Current spending by the GLA for 2017-18 and its revenue sources

| £bn | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Total spending | 11.758 | |

| Revenue sources | ||

| Fares | 4.877 | 41 |

| Whitehall grants | 2.610 | 22 |

| General income | 1.405 | 12 |

| Business rates (GLA retains) | 1.307 | 11 |

| Council tax | .805 | 7 |

| Paid to Whitehall from business rates | .754 | 6 |

| Total revenue | 11.758 | 100 |

Note: Fares, general income, GLA-retained business rates and council tax are locally generated revenues.

This situation may look quite favourable, but Whitehall grants were severely cutback in the austerity period (2010-17), with drastic consequences for London police and fire services where personnel numbers had to be greatly reduced. Central departments also control much of the GLA’s vital capital budgets, which are very large because of major transport projects.

The London Finance Commission, first formed by the Mayor in 2012, recommended that the GLA should take on complete responsibility for a wide range of taxes such as council tax, stamp duty, business rates and capital gains tax. This change would be accompanied by a reduction in central funding for the Authority, thereby increasing its autonomy and responsibility. The Commission has also supported the idea of new taxes, such as a levy on tourism. A 2017 report lays out the scope for further functions to be devolved to the capital, building on the momentum for more powers to be devolved to cities or city regions within England.

Two tier government

One reason why the GLA’s predecessor London-wide body was abolished by the Thatcher government in the mid 1980s was conflict between the Labour GLC and many of the 32 London boroughs under Conservative control, produced by an overlap of functions. So the design of the GLA was designed to keep the mayor (and especially the constituency Assembly members) from interfering in purely local issues. This design aim has generally been achieved, but there are inevitably some tensions between the more dynamic GLA and the small and slower-moving London Boroughs – e.g. over plans to build more affordable housing to combat the capital’s crisis of housing costs that are well above ordinary Londoners’ ability to pay.

Conclusions

London’s strategic government has succeeded far better than its creators could have envisaged. The London mayor is an internationally known representative of the capital, and all five mayoral terms have created strong electoral legitimacy for the office-holders. By contrast the Assembly has been inhibited by its lack of powers from playing a major role or establishing a strong public profile.

London-wide issues have been successfully addressed by the GLA, especially on transport improvements and road charging. But policing, homeland security, responding to Brexit and other areas have been hampered by continued Whitehall interference. The current system may seem ‘entrenched’, but rash proposals to wreck the mayoral voting system in the Tory 2017 manifesto show that some in Westminster still refuse to recognise the reality that devolved powers are devolved.

This post does not represent the views of the LSE.

Andrew Blick is Lecturer in Politics and Contemporary History at King’s College London.

Patrick Dunleavy is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the LSE.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.