Audit 2017: How democratic are the key institutions of devolved government in Wales?

Devolved government in Wales started as a radical innovation in bringing government closer to citizen. Its generally successful development has generated great expectations about the National Assembly for Wales and the Welsh government acquiring more powers – and perhaps being reformed in some respects. As part of the 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Jac Larner and the Democratic Audit team explore how democratically and effectively these central institutions have performed.

Welsh flags flown at the Senedd on St David’s Day. Photo: National Assembly for Wales via a CC BY 2.0 licence

This article was published as part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy. We have now published: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit with LSE Press, available in all ebook formats. You can download the whole book for free, and individual chapters, including a fully revised version of this article.

What does democracy require of the devolved National Assembly and government in Wales?

- The legislature should normally maintain full public control of government services and state operations, ensuring public and Assembly accountability through conditionally supporting the government, and articulating reasoned opposition, via its proceedings.

- The National Assembly for Wales (sometimes known as the Senedd from its main building) should be a critically important focus of Welsh political debate, particularly (but not limited to) issues of devolved competence. It should articulate ‘public opinion’ in ways that provide useful guidance to the Welsh government in making complex policy choices.

- Individually and collectively legislators should seek to uncover and publicise issues of public concern and citizens’ grievances, giving effective representation both to majority and minority views, and showing a consensus regard for the public interest.

The Welsh government should govern responsively, prioritising the public interest and reflecting public opinion across Wales.

The current institutions were implemented as part of the Blair government’s devolution settlement, and were endorsed by Welsh voters in 1997. The National Assembly for Wales in Cardiff has 60 AMs, elected by only a very roughly proportional representation system (the additional member system). It has fewer powers than the Scottish Parliament. The Welsh Government accounts to the Assembly for how it runs all the devolved policy areas. The government is currently headed by the Labour Party leader, First Minister Carwyn Jones who heads a coalition of Labour and the Liberal Democrats drawn from the Assembly.

The Labour party drew up the initial plans for the Assembly in a one-party way, without the cross-party Constitutional Convention that operated in Scotland. There is an Additional Member System voting method, with 40 constituency AMs, most of whom have always been Labour. There are only 20 seats to allocate at the top-up stage (33%), far less than in Scotland or London, and too few to achieve more than very rough proportionality. Labour has been continuously in power in Cardiff since 2000 – in sole power for nine years, and otherwise in coalition governments. In the early run-up to the 2017 general election there were some predictions that its predominance in representing Wales at Westminster would be decisively reduced, but these turned out to be incorrect.

Recent developments

Wales has received a good deal of funding from the European Union in recent years, but the country nonetheless voted to Leave (52.5%) at the Brexit referendum. The Brexit process is likely to have wide-ranging effects for devolved democracy and governance in Wales. Chief among these is the potential transfer of policy competencies directly from the EU to the National Assembly. The Wales Act (2017) changed Wales’ devolution settlement from a conferred model (where Westminster lists what the devolved government can do) to a reserved model (where Westminster instead lists the powers reserved to the UK government). All other things being equal, this change means that areas of EU policy that are not explicitly reserved should therefore be transferred to the Assembly. This might include additional controls and regulations over the environment and agriculture. Farming is a particularly important issue for Wales, considering that 90% of Welsh agricultural exports go to the EU, and that 80% of Welsh farmers’ income comes from the common agricultural policy (CAP).

However, Whitehall has suggested that some of these powers (such as agricultural subsidies) may be stripped from devolved competency and placed centrally in the hands of Westminster. For this to come about the Sewell Convention (governing Westminster/devolved country relations) would seem to require the consent of the devolved legislatures. Such an interpretation may be disputed by the UK government, creating potential for a future legal struggle between Westminster and the devolved legislatures.

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

| The National Assembly for Wales has long been regarded as a success story with regards to representation. | The National Assembly has not seemed to be a relevant institution in the day-to-day lives of the Welsh public. So the low levels of participation and interest in the institution have been low. |

| In 2003, the Assembly made waves worldwide as the first national legislature in the world to achieve a 50:50 gender balance. Following a by-election in 2006 Wales took a step further, with female AMs outnumbering their male counterparts in the Senedd for a brief period – neatly reflecting Wales’ demography where women make up 52% of the total. | Since 1999 low levels of voter engagement have been a constant issue for the National Assembly, with mean turnout for its elections a relatively low 43%. This is 21 per cent points lower than the average Welsh turnout for general elections in the same period. And it lags behind average turnout for the Scottish Parliament (53%), and the Northern Ireland Assembly (61%). |

| These results largely reflect the electoral dominance of Welsh Labour and the positive measures to promote gender equality that it put in place. ‘Twinning’ of constituencies and ‘zipping’ on the party’s top-up candidate lists both mean that men and women must alternate in being successful. So Labour has an impressive record on women’s representation: 55% of Welsh Labour’s constituency AMs and 71% of their top-up list AMs since 1999 have been women. Plaid Cymru have also enacted some positive measures themselves - so 51% of Plaid List AMs have been women, 27% of constituency AMs. | Enthusiasm for devolution has historically been lukewarm in Wales. The 1997 referendum, which asked voters if they wanted a National Assembly for Wales, had a turnout of only 50% (compared to 60% in the equivalent Scottish referendum). The endorsement of the proposals was just 50.3% of votes cast, far less enthusiastic than in Scotland (74%). |

| The 2011 referendum on further powers for Wales provided a far more positive result for proponents of devolution. Some 63.5% of the population voting in favour of giving the Assembly more powers - yet only 35% of registered voters turned out to vote. |

| Future opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| The fifth Assembly has seen a willingness between parties to work together to achieve a more accountable politics in Wales. After a shaky start, an early agreement between Welsh Labour and Plaid Cymru laid the groundwork for projects that the parties would work together on. | Brexit is likely to be the biggest challenge that the Assembly and Welsh government have faced in its relatively short existence. The potential repatriation of powers from the EU to the Assembly, and any legal battles with the UK Government that may accompany them, will test the capacity of the Welsh political institutions. |

| With the formation of the nonpartisan Expert Panel on Electoral Reform in the Assembly, there is now a real chance that electoral reform and a reshaping of the Assembly could gain cross-party support. Any proposal would still have to pass the super-majority threshold of two-thirds support, but it is at least a possibility. | These events will occur almost simultaneously with the devolution of tax powers (which could encounter implementation difficulties) and a reduction in the number of Welsh MPs at Westminster (weakening Wales’ voice within UK institutions). |

| The devolution of taxes will also bring a new level of accountability to the Assembly. For the first time the Welsh Government will be at least part responsible for raising the funds it spends. This will bring a new relevance to the Assembly, and it will have to step-up and become an open and more effective place for debate and scrutiny in Welsh politics. |

Voting systems

The new Expert Panel on Electoral Reform may decide that there is a need for the Assembly to increase its capacity, probably implying a change to the electoral system. The British-style Additional Member System (sometimes called Mixed-Member Proportional or MMP) gives voters two votes, one for a candidate in a constituency, where the winner is decided by plurality voting (‘first past the post’), and one for regional members allocated to even up overall party regional seat shares with their votes there. Critics in Wales argue that it is confusing for voters to use. Others argue that if only the number of top up seats was increased (giving a somewhat large Assembly) more proportional outcomes would follow. Any changes are likely to be hard-fought however, as they would require a super-majority of two-thirds support in the Assembly. A large amount of support from Welsh Labour AMs (who have benefited greatly from the status quo) would be needed for any change to pass.

There have also been moves to examine the electoral system used in local council elections in Wales. In a January 2017 white paper, Reforming Local Government: Resilient and Renewed the Welsh government focused specifically on ‘Elections and Voting’ (section 7). Among other things, it discussed whether the voting age should be lowered to 16 (as in Scotland now); whether candidates should have to declare whether they are a member of a political party (even if not standing for that party); preventing ‘dual mandates’ where sitting AMs are also elected as councillors; and the voting system to be used at council elections (which is currently plurality rule or FPTP). Surprisingly, the white paper floats the idea that each local authority might be able to individually decide whether they maintain the FPTP system, or to swap to a Single Transferable Vote (STV) system, as used in Scottish local government. This could mean that rather than a unitary election system for council elections in Wales, it would vary from one local authority area to another. Careful consideration will be needed here since Welsh voters are already using multiple differing electoral systems; First Past the Post (FPTP) at general elections; multi-member FPTP at local council elections, AMS at Assembly elections, and the Supplementary Vote (SV) for Police and Crime Commissioners. Even more variation within Wales might create more confusion, and hurt engagement further.

Senedd reshaping proposals

The Wales Act (2017) provides the Assembly with powers over its own affairs. This translates into the Assembly having the ability to change its name and many other features. In recognition of this, Y Llywydd (the Presiding Officer) has formed an expert panel on reforming the Assembly to examine three key areas: the number of AMs, the electoral system and the minimum voting age.

With only 60 sitting AMs, recent political developments have raised questions over the Assembly’s capacity to be an effective and accountable legislature that is able to provide scrutiny to the Welsh Government. The potential repatriation of powers from the EU to the Assembly, Brexit negotiations, and the devolution of tax powers over the next few years will be a significant test for the institution. This is further compounded by a likely reduction of over a quarter of Wales’ MPs at Westminster, recommended by the Boundary Commission for Wales (cutting their numbers from 40 now to 29). This is the largest proportional reduction of any of the four nations of the UK.

The media system in Wales

Part of the Assembly’s problems reflect the fact that Wales has never had a strong domestic media presence (unlike Scotland). Welsh Election Study (WES) data showed in 2016 less than 7 per cent of the electorate in Wales read a ‘Welsh’ newspaper. UK papers do not provide ‘Welsh editions’, again unlike Scotland. Typically they almost never contain information or news about the Assembly or politics in Wales. Furthermore, there is also a serious lack of diversity among the printed press in Wales. WES data show that the three most widely read Welsh papers were the Western Mail, South Wales Echo and the Daily Post, all owned by Trinity Mirror (traditionally backing Labour in its lead title the Daily Mirror). The most visited Welsh news website, WalesOnline, is also owned by Trinity Mirror.

Welsh broadcasting has broader reach, but many constraints. On television, news content about the Assembly or Welsh Politics must fit within a 15-minute supplement that follows the UK news on BBC or ITV. Some 42% of WES respondents reported watching Wales Today on BBC Wales, and 17% Wales Tonight on ITV Wales. Radio is a similar story to the Welsh press, with only 15% of respondents saying that they listened to Welsh radio programmes. Further analysis of this data suggests it is largely the same people who read/watch/listen to Welsh content. So a significant proportion of the Welsh electorate is rarely if ever exposed to information about what happens in the Assembly, or Welsh politics more generally. The situation looks unlikely to improve in the future. While the BBC has recently announced it will create a new TV channel in Scotland with a dedicated hour of Scottish news programming the step was not matched in Wales. Instead, Wales is to receive £8.5 million a year in extra funding

Support for Welsh independence

Unlike Scotland, support for Wales to become an independent country has never been extensive, so that relatively little polling is carried out on the issue. When asked as a binary question (independence: yes or no?) support in recent years has ranged from 14% in May 2014 to a high of 17% in September that year. Immediately after the Brexit referendum, this increased dramatically to 28% when respondents were primed with the idea that Wales could thereby remain in the EU.

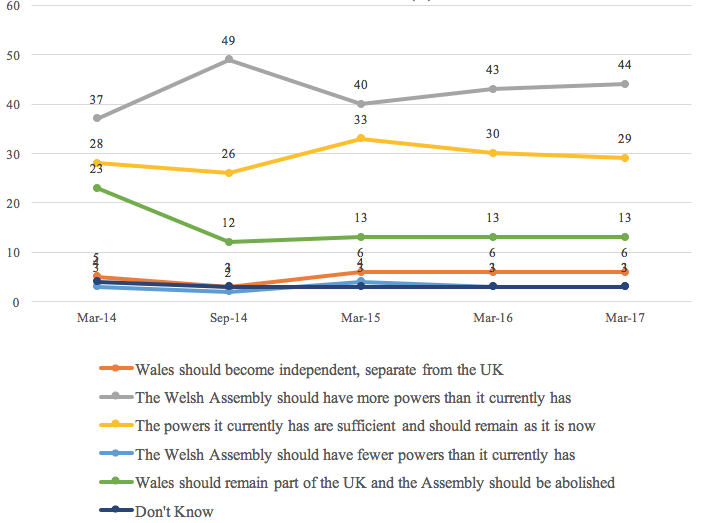

A more detailed range of options shows that support for independence in Wales is perhaps even lower still. Figure 1 shows the results of five BBC/ICM polls since early 2014 that gave more options to voters. The stability of constitutional preferences is striking and the order of Welsh voters’ preferences remains nearly constant despite Scotland’s ‘IndyRef’, the 2015 general election, the 2016 Welsh election and Brexit all occurring over this period. Here support for Welsh independence was just 6%. However, close to half of respondents favoured more powers for the Assembly, while around 30% thought its existing powers sufficient.

Figure 1: BBC/ICM St David’s Day poll (2014-17): respondents’ constitutional preferences

Conclusion

As Figure 1 shows, devolution now seems to be the settled will of the Welsh people. Yet the National Assembly for Wales and the Welsh government face uncertain times ahead as the Brexit-fuelled transfers of power from the EU test its competence, capacity, and ability to adapt to rapidly changing circumstances. New tax powers will also accrue to Cardiff. The challenge for both, especially for the National Assembly, will be to become more well-known, effective and accountable bodies at the heart of politics and governance in Wales.

This post does not represent the views of the London School of Economics.

Jac Larner (@Jaclarner) is a research student at the Wales Governance Centre, Cardiff University. His research seeks to understand the determinants of electoral choice in Wales.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.