Book review | A Woman’s Work, by Harriet Harman

In A Woman’s Work, Britain’s longest-serving female MP Harriet Harman offers a new memoir reflecting on her experience of high-level politics and the recent history of the Labour Party from the late 1970s to the present. Despite a small number of notable omissions, this is a valuable addition to the genre of political autobiography that puts women’s lived experience and the continuing fight for gender equality at its centre, writes Emma Lundin.

Harriet Harman returns to the Commons in May 2015 as acting leader of the Labour Party after Ed Miliband’s resignation. Photo: Jessica Taylor/ UK Parliament under parliamentary copyright.

If you are interested in this book review, you may also like to listen to a recording of Harriet Harman participating in a LSE Literary Festival 2017 panel on ‘Women in Work: An Unfinished Revolution?’, speaking alongside Katrine Marçal, Lieutenant Commander Alexandra Pollard and Dr Nicola Rollock on 23 February 2017.

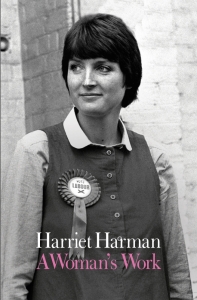

A Woman’s Work. Harriet Harman. Allen Lane. 2017.

In what we can hope is a lasting trend, there has been a lot of interest in books that restore female politicians’ lives and experiences to the historical record over the past year. Alongside historian Laura Beers’s Red Ellen: The Life of Ellen Wilkinson, Socialist, Feminist, Internationalist, journalist Sophy Ridge’s The Women Who Shaped Politics and Labour MP Rachel Reeves’s Alice in Westminster: The Political Life of Alice Bacon sits Harriet Harman’s A Woman’s Work – a rare autobiography written by a woman still involved in high-level politics, and an engaging account of a tumultuous time in the Labour Party’s history.

In what we can hope is a lasting trend, there has been a lot of interest in books that restore female politicians’ lives and experiences to the historical record over the past year. Alongside historian Laura Beers’s Red Ellen: The Life of Ellen Wilkinson, Socialist, Feminist, Internationalist, journalist Sophy Ridge’s The Women Who Shaped Politics and Labour MP Rachel Reeves’s Alice in Westminster: The Political Life of Alice Bacon sits Harriet Harman’s A Woman’s Work – a rare autobiography written by a woman still involved in high-level politics, and an engaging account of a tumultuous time in the Labour Party’s history.

Harman charts Labour’s continuous spiral of rise and fall from the late 1970s until 2016, and questions its commitment to women – whether those in the party or the electorate – throughout. Harman is brave enough to lay her emotions bare: afforded strength and privilege to oppose the status quo through her affluent upbringing, she was all the more frustrated to realise the extent to which sexism, misogyny and violence made her and other women vulnerable. It is striking that someone who has had the power to influence and execute policy at a national level has nonetheless felt powerless on so many occasions.

One of fewer than twenty women in parliament when she was elected in 1982, Harman has had to put up with abusive and belittling remarks from political opponents, supposed allies, the press and the public ever since. She became involved in the Labour Party because it was, she argues, the only party that could possibly address the lagging social and legal rights for women in the UK, and feminism has impacted everything from how she has staffed her office to the way she works. As a result, the book is an excellent source for those of us who study the role of women within large, male-dominated parties: it clearly shows how women working as a collective within a larger mixed-gender organisation are cast as divisive, troublesome and potential traitors. This is the double-bind of women’s activism: women have to organise as a lobby to have an impact on policy, but in doing so, they risk exclusion and stagnating career trajectories.

Women can also fade from view: the book is, Harman writes in her postscript acknowledgements, an attempt to show the importance of women in Labour Party history. She specifically addresses the autobiographies by her male contemporaries, who have written Harman and other women out of their stories. Instead of mimicking them, Harman outlines the importance of the collective to feminist ideology, and shares some of her spotlight with lesser known office and support workers – including Scarlett MccGwire and Deborah Mattinson – effectively bringing them into the history of the party with her.

One of the strengths of the book is that Harman does not shy away from intra-party conflicts: her grievances with unfulfilled promise and the passive resistance from male colleagues who pay lip service to feminism as well as her disappointment with the slow pace of reform within the Labour Party are all laid bare here. She was an eyewitness to Tony Blair and Gordon Brown’s friendship from beginning to end, and is scathing about Peter Mandelson’s role in its breakdown (164-65). She is critical of David Miliband’s attitude when losing the leadership race to his younger brother, arguing that the former should have looked to Alan Johnson’s gracious defeat to Harman when running for deputy leader for a lesson in how to bring warring party factions together (272, 332). She argues that if her Equality Act had been implemented in 2007 rather than in dribs and drabs between then and 2010, it would have gone a long way to address the white working-class concerns that allegedly caused the Brexit result. It could even, she says, have silenced the ‘ultra left’ in the party (297).

Still, there are areas and eras where Harman could be more explicit. Like so many autobiographies, the book benefits from hindsight in the earlier chapters where the author is more reflective than in the information-packed second half. This is a result of Harman’s refusal to keep a diary – she ‘thoroughly disapproved of colleagues who sat in meetings writing theirs’ (385) – and her reliance on monthly reports written for her Constituency Labour Party. While readers’ appetite for gossip is mostly satisfied, we don’t find out why Harman faced such animosity from John Prescott (perhaps we can imagine – but is it too simplistic to ascribe it to a given conflict between the posh southern woman and the working-class northern man?). And her decision not to put her name forward for party leader in 2010 and 2015 is far from clear: why leave it to Diane Abbott to stand as the token woman in 2010, particularly after Harman’s successful deputy leader election in 2007?

Frustratingly, Iraq is also skirted over: Harman points out that her vote in favour of war was based on information that was later proven incorrect, and her understanding – built on testimonies from Iraqi exiles – that Saddam Hussein was a ruthless, vindictive and untrustworthy dictator. But she does not touch upon the ripple effect of violence, the cost of war and consecutive humanitarian disasters in the wake of the invasion (253-54).

Elsewhere, Harman credits the women’s movement with giving her the most important push towards a political career, but she speaks of the movement in a disembodied way. Readers might ask how Harman kept herself up-to-date with agendas and strategies throughout her busy career: who made up the movement, and what was Harman’s role within it? While she correctly argues that the movement for women’s rights is international, she fails to connect her story to these venues – apart from in a short section on twinning with Tanzanian MP Monica Mbega. It is also peculiar that political journalist Gaby Hinsliff suffers from a misspelled surname (‘Hinchliffe’) in a paragraph about the importance of women in the Westminster press corps (84). Perhaps, in light of the recent election, A Woman’s Work was published too soon: Harman is critical of Jeremy Corbyn’s chances of surviving as Labour leader in the book, but was quick to acknowledge that she had underestimated him on 9 June 2017.

Despite these shortcomings, A Woman’s Work is an invaluable addition to political auto/biography and, as a welcome interjection, it deserves to be widely read. Harman shows the importance of lived experiences to political life and how parliament must reflect the nation it seeks to represent. She outlines the role of cold, hard facts in forcing through unpopular equality reforms, and argues that there is much left to do to close the gender gap. The fight is far from over: in her epilogue, Harman puts forward the criteria to assess whether Theresa May helps women during her term as prime minister (377), before closing with a ten-point feminist manifesto that, among other things, tells us that we ‘should be gratified that we have made so much progress, but we should never be grateful’ (379). It is a good reminder that we have come far, but never far enough.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It first appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Emma Lundin is a historian with a particular interest in 20th-century liberation movements and philosophies from Scandinavia to southern Africa. She completed her PhD in 2015 and has taught at Birkbeck, UCL, King’s College London, Goldsmiths and Queen Mary, University of London. She is currently working on a research project on the cross-border spaces created and inhabited by female politicians in the late 20th century and tweets @emmaelinor.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.