Audit 2017: How strong is the democratic integrity of UK elections? Are turnout, candidacies and participation maximised?

Across the world, there are many countries ‘where elections take place but are rigged by governments or unfairly conducted. And even in core liberal democracies (like the United States) political parties have now become deeply involved in gerrymandering constituencies and partisan efforts at ‘voter suppression’. As part of our 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Toby S James looks at how well elections are run in the UK, and whether the systems for registering voters and encouraging turnout are operating effectively and fairly.

Outside a north London polling station, June 2017. Photo: Ros Taylor

This article was published as part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy. We have now published: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit with LSE Press, available in all ebook formats. You can download the whole book for free, and individual chapters, including a fully revised version of this article.

What does democracy require for the conduct of elections, and how are voting, candidacies and fair competition facilitated?

- Governmental and legislative offices are open to popular competitive elections. All citizens have the right to take part in the electoral process. All parties, interests and groups assign great importance to maintaining universal and equal voting rights and to encouraging electoral participation.

- All votes count equally. So constituencies for all legislatures are (broadly) equal in size; and seats are (broadly) distributed in proportion to population numbers. Some variations in the population sizes of seats in order to facilitate more effective ‘community’ representation are allowable.

- The registration of voters is impartially organised in timely, speedy, convenient and effective ways. It maximises the ability of all citizens to take part in voting. Resources are available to help hard-to-register groups to be enrolled on the register.

- Voting in all elections is easy to do and the administrative costs for the citizen are minimised. Polling stations are local and convenient to access, there are no long queues for voting, and voters can also cast votes conveniently by mail or online. Arrangements for proxy voting are available. All modes of voting are free from intimidation, fraud proof and robust.

- All citizens can stand for election as candidates, and they face no onerous regulatory or other barriers in doing so. Some requirements for signatures or deposits are allowable in order to obviate frivolous or ‘confuser’ candidacies (also called ‘passing off’). But they must be kept low and proportional to the seriousness of the offices being contested. All parties and groups assign top importance to maintaining candidacy rights and facilitating effective electoral competition and maximum choice for voters.

- Political party names and identifying symbols can also be registered to prevent ‘passing off’ strategies designed only or mainly to confuse voters. (Registering party names is also essential in most PR systems where candidates are elected off lists). But otherwise party or candidacy names may be freely chosen, and candidates can describe themselves in any legal way.

- All aspects of the electoral process are run impartially by trained, professional staffs in secure ways that minimise any opportunity for fraud. Election administrators have the legal ability to curb electoral abuses and to ensure that all candidates campaign legally and within both the electoral rules and the normal legal requirements to show respect for other citizens. Police and prosecution services impartially investigate and pursue all allegations of electoral misconduct or corruption and prosecute when necessary in a timely manner.

- Incumbent governments at the national level and sitting MPs or members of legislatures at constituency level must compete at elections on fully equal terms with all other parties and candidates. They enjoy no special advantages.

- Elections should always be welcoming and safe opportunities for voters and candidates to express their views, whatever their political affiliations or social background. Elections must never be occasions for intimidation or the worsening of social tensions.

- Election conduct and counting processes should be transparent and subject to inspection by parties and candidates, and by external observers. Election processes and results should be accepted by all domestic political forces as fully free and fair, and rated in the same way by foreign observers.

- The media system should be a pluralistic one, handling the reporting of elections and campaigns in a reasonably fair and diverse way. There should be no direct state interference in the reporting of elections or campaigns designed to secure partisan advantages for the incumbents or for powerful parties.

Free and fair elections are essential for the democratic process, and the UK implemented many of the requirements for them (including limits on local campaign spending) by the 1880s, although it didn’t fully extend the franchise until 1928. The effectiveness of inherited and long-unchanged rules, administration and practice of elections changes over time, however. As society changes, the effect of rules can drift. The UK doesn’t have electoral irregularities on the scale commonly seen in competitive authoritarian states or ‘semi-democracies’ (where voting takes place but under rigged arrangements) or the almost unrestricted corporate funding of elections in the USA. However, there are old and new pressures on electoral integrity in the UK.

Recent developments

The UK is not short of elections. The long-term trend has been towards an increase the number of positions in which citizens can elect representatives for office (and more frequent referendums). Devolution, the introduction of Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC) elections, and new mayoral elections all made voting a growing feature of the political landscape. This trend has not always succeeded, however. Health board elections were introduced but then scrapped in Scotland. The low turnout in PCC elections means that their future remain uncertain. Most significantly, there has been no movement towards electing the House of Lords.

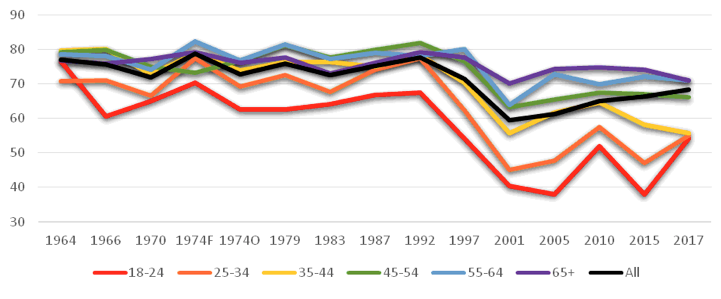

Recent continuity in the number and types of elections does not mean that we’ve seen little change in how they are run or how voters participate. The most publicised development has been the reversal of the long decline in turnout in UK general elections. From the nadir of 2001, turnout rose by nearly 10 percent points to 68.5 per cent in the 2017 general election. Moreover, it grew substantially amongst one of those groups who were increasingly not exercising their democratic right – young people. In 2005 the UK had the largest ‘age gap’ of any liberal democracy in the gulf between voters over 55 and under 34. However, Chart 1 shows that turnout amongst the 18-24 and 25-34 age categories substantially rebounded in June 2017. The age gap from 2005 and 2015 was effectively halved.

Chart 1: The estimated turnout of different age groups at general elections from 1964 to 2017

Source: Computed by author using data from the British Election Study, IPSOS Mori and BBC.

Yet there remains cause for concern. Differentials between age (and other) groups have not disappeared. The method for calculating turnout in the UK (as a percentage of registered voters) makes it look higher than it really is. Turnout remains chronically low for other electoral contests. The recent rise in general election turnout owes much to major changes in British party politics, and very little to changes in Britain’s electoral machinery. A new cleavage has opened-up based on age, education and social values rather than social class. Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party has successfully focussed on gathering support from a new electoral block – with the newly re-energised youth a key part of this. Whether this engagement will be sustained remains uncertain.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Elections are generally very peaceful, and intimidation or electoral fraud rarely occur, although there are isolated problems. Election results are well respected by parties and citizens. International observers have regularly expressed ‘a high level of confidence in the electoral process.’ | The most important problem is incomplete electoral registers, owing to a system where it is an individual and not a state responsibility to ensure names are on the electoral roll. Many citizens fail to re-register because they misunderstand the electoral registration process. Estimates suggest that up to 8 million citizens may be missing from registers in recent contests, around 16% of the adult population (see below). |

| It is very straightforward to register a party or to stand as a candidate at UK elections, with very few regulatory impediments. An election deposit of £500 is required to stand as an MP for Westminster, returnable if the candidate gets 5% of the votes. Higher deposits apply for police commissioner elections (£2000). Candidates also need relatively few registered voters to sponsor their standing (10 for Westminster). | At £500 per seat, the deposit cost of contesting every seat in Britain at a general election is £314,000. This still favours the most established parties over newcomers. In 2017 candidacies for UKIP fell sharply by 346 compared to 2015; and those for the Green party by 106. This partly reflected lack of finance, and less time to raise finance since the 2015 general election. |

| Procedures in polling stations are simple and liberal: for example voters do not need to show ID but just give a name and address. This makes voting very speedy to do and facilitates. Polling stations are also very locally situated (mainly in primary schools or community centres), and most locations stay the same from one election to another and become familiar to citizens. | There is an archaic, antiquated and illogical system for determining who is allowed to vote (see below). For instance, in Scotland teenagers of 16 and 17 can vote in elections for the Edinburgh Parliament and local councils, but not for Westminster MPs. And in all other UK countries they cannot vote at all. |

| The UK’s boundary review process responds to statue and its implementation timing is often politically influenced. However, the process of defining constituencies is separate politicians and prevents gerrymandering. | The robustness of electoral finance regulation is problematic at the margins (see below). Constituency spending limits are set restrictively, but national spending levels are unrestricted. |

| Electoral administration is chiefly run by professional officials in local government who are independent from government and local politicians. The Electoral Commission is a national quasi-government body that regulates electoral finance and advises on election procedures in an independent way. It has shown plenty of willing to criticise the government when necessary. | The legislative framework is 'complex, voluminous and fragmented' and in need of consultation. Isolated cases of electoral fraud remain. Some vulnerabilities in electoral registration remain. The system for securing electoral justice is archaic and slow. |

| A modernised online electoral registration system has enabled many last minute voter registration applications. Timely registration for upcoming contests is much better developed than in the past. | Locating electoral administrators in local governments means that many are operating under financial restraints, following many years of austerity cutbacks. Systems for registration are often dated. Arrangements for the effective communication of results back to voters are online are problematic. The apparatus for communicating with voters was basically defined in the 1880s and though candidates are listed on websites the approach has otherwise been little updated for the social media era. Cutbacks have especially restricted voter outreach work by local authorities. |

| Civil society groups and NGOs (such as ‘Bite the Ballot’) have organised to register and engage voters. They helped to set out policy ideas through a parliamentary group. Voter advice applications also seek to reach people at general elections who are not normally politically engaged. And sites such as Democracy Club and Democratic Dashboard contribute to the provision of information to citizens. | Further deficiencies in UK elections lie outside the area of ‘electoral integrity’ itself. The Westminster electoral plurality voting system (also used in English and Welsh council elections) often produces highly disproportional results. In the media system the newspaper coverage of candidates and parties remains systematically unbalanced. |

| There remains little or no citizenship education. |

| Future opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| The Scottish government may bring legislation forward to reform Scottish electoral law and Welsh government is reviewing local elections in Wales. This could also provide opportunities for innovation and learning across the UK. | Proposals to make voters show ID at future elections could discourage voters from going to the polls, and make it more difficult for many citizens to vote. |

| Brexit negotiations offer an opportunity for the concept of citizenship to be redefined and electoral rights to be realigned. | Political advertising via social media is currently very little regulated (see below) |

| UK-wide pilots of automatic registration could lead to cost efficiency savings, but may also strengthen levels of voter registration. | Under the new Individual Registration systems electoral turnout and registration levels may drift downwards at subsequent elections without high profile electoral events. |

| A debate has opened up about the funding of electoral serviceswith the Scottish Local Government and Communities Select Committee reviewing arrangements. | Brexit negotiations may leave many EU citizens with fewer electoral rights. |

| The Higher Education and Research Bill requires universities to play a role in student registration. There are therefore opportunities for innovation in, and learning from, voter registration activities. | |

| The Law Commission's proposals to consolidate the UK’s ‘complex, voluminous, and fragmented’ sets of electoral law was published in February 2016 – but the government has not yet said what (if anything) it will do about it. |

Electoral registration changes

Online electoral registration has recently been introduced, which was a massive step forward in the modernisation of elections – and in 2016 and 2017 prevented much of the anticipated decline in levels of electoral registration. The responsibility for registering voters in each household used to rest with the ‘head of household’, a system that worked pretty well but rested on archaic assumptions. However the new system of individual electoral registration (IER) made it an individual responsibility to register to vote and ask citizens to provide their national insurance number. The consequences of IER have been profound, if often unseen, for the running elections. Forthcoming research shows that the weight of administrative reform sucked up additional resources from local authorities and led to many experienced employees leaving the profession. There were fears that IER would lead to young voters and those moving areas being left off electoral registers. However, some counter-mobilisation efforts from civil society took place, with support from the government’s Democratic Engagement Strategy. Established in 2015, it provides some funding for a range of NGOs to undertake voter outreach work. Legislation was also passed to require universities to play a role in registering their students, one of the most under-registered groups. Moreover, civil society has played a much greater input into policy, with the All Party Parliamentary Group on Democratic Participation forming and publishing influential reports.

Who is eligible to vote?

The electoral franchise, which is defines who has the right to vote, is an essential part of what it means to be a citizen within a polity. Excluding people from it immediately builds in political inequality. The UK’s electoral franchise is an antiquated patchwork of historical legacies that lacks any underlying principles. Citizens from qualifying Commonwealth countries and Ireland can move to the UK and have full electoral rights immediately. Yet a citizen from the European Union, who has lived and worked in the UK for most of their life, has rights for local and European elections (while they last) but not for Parliamentary elections, nor for major electoral events like the EU referendum. Recent electoral events have affected them more than any other group of people. The Scottish Parliament has granted 16 year olds the right to vote in Scottish local and parliamentary elections. But they can’t vote in Westminster elections, or in any other part of the UK. Lords amendments to grant 16 year olds the right to vote in the Eu referendum were rejected by the government and Theresa May has since restated opposition to extending voting rights to 16 years olds.

This is hugely significant as new electoral cleavages open up in Britain. Many recent electoral contests, which are having profound consequences for public policy may have had entirely different electoral outcomes if the franchise was different. It is currently unjustified, unbalanced and unequal. Meanwhile, the UK continues to breach the European Convention of Human Rights in denying prisoners (other than those on remand or serving sentences for contempt of court) their vote while serving their sentence.

Where the Conservative governments have been proactive in expanding the franchise is for British overseas electors. The 2017 Tory manifesto promised them votes for life (compared with the current system where expats retain the franchise only for the first 15 years that they live overseas).

Fraud and malpractices

The main focus of policy in 2015-17 under the David Cameron and Theresa May governments was less about promoting democratic engagement and more about reducing opportunities for electoral fraud. The government announced a programme to trial voter ID in the May 2018 local elections. But before those trials could be organised, the Conservatives also made a manifesto commitment at the 2017 election to legislate for voter identification, following completion of the transition to individual electoral registration. Under the pilot proposals, citizens in Britain would leap from having no identification requirement to having some of the most restrictive. This could lead to many people being denied their right to vote because they do not have sufficient paperwork to hand on election day.

Yet there is very little evidence that there is a problem to be solved. It is true that the absence of a requirement to provide any form of identification at polling stations places Britain out of line with international practices. But the overall number of cases of electoral fraud under this ‘high trust’ system is exceptionally low. Table 1 shows that this was a tiny problem at the 2015 general election.

Table 1: Problems experienced by poll workers at the British general election 2015

| Type of problem reported | % of poll workers reporting | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No cases | One case | 2-5 cases | 6-10 cases | 10+ cases | |

| People asking to vote but not on register | 31 | 16 | 39 | 10 | 3 |

| People ask to vote whose identity I was unsure of | 94 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| People taking photos of ballot/ polling stations | 95 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Members of parties being where they shouldn't be | 95 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Members of parties intimidating the public | 95 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Suspected cases of electoral fraud | 99 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Source: Clark and James, 2017

The ‘missing millions’ of unregistered citizens

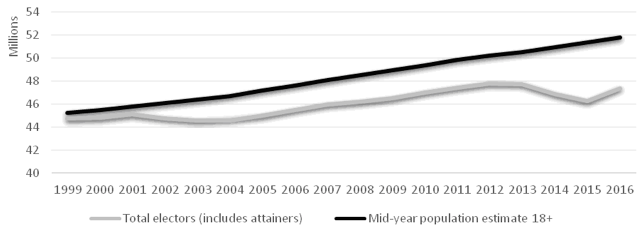

Table 1 also confirms that the more significant problem is citizens turning up to vote only to find themselves not on the electoral register. This confirms other research which shows that many citizens think that their name is on the electoral register because they access other government services and pay their council tax, when they often are not. Chart 2 shows there has been a gradual rise in the number of people missing from the electoral register. If everyone was registered, the number of people on the electoral register should be roughly in line with the annual mid-year population estimates. But there has been a growing gap. This gap also understates the number of unregistered voters because if there are duplicates, which there are, then there are many more people missing. The most complete assessment is that there could be up to 8 million people missing.

Chart 2: The growing gap between the eligible total number of citizens/inhabitants and total electors

Source: Author compiled from ONS Population Estimates and Electoral Statistics from 1 December each year. The local electoral register is used because it has the higher franchise.

There is further political inequality here. Under-registration is not equally distributed across the whole population. The evidence is that the register is less complete in urban areas (especially within London), amongst recent movers and private renters, Commonwealth and EU nationals, non-white ethnicities, lower socioeconomic groups, citizens with mental disabilities and young people. This matters more than ever before because this is the register on which the boundaries for the 2020 general election will be drawn. These groups will have less representation in the UK Parliament than others.

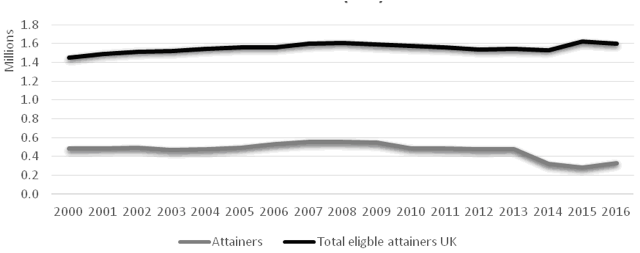

The most worrying trend is with attainers – citizens who will shortly reach the voting age during the currency of the forthcoming register. These have historically just been 16 and 17 year olds, as only 18 year olds can vote. But the because the Scottish Elections (Reducation of Voting Age) Bill lowered the voting age for some elections in Scotland, attainers can now be 14 or 15. Chart 3 shows that there has been a longer term decline in the number of such electors on the register. The darker line indicates the mid-year population estimates of 16 and 17 year olds in the UK but includes 14 and 15 year olds in Scotland after 2015. The lighter line indicates actual numbers of attainers on the register. In short, the next generation of voters are largely missing from the register.

Chart 3: The gap between eligible attainers (people nearing voting age, who should be on the electoral register) and registered attainers

Source: Author compiled from ONS Population Estimates and Electoral Statistics. The local electoral register is used because it has the higher franchise.

There are two principal short-term causes. The move to individual electoral registration was predicted to hit young people the hardest since their parents often previously registered them. Second, electoral registration efforts in Scotland may not have caught up with the new franchise. Simple solutions include the automatic registration of young people at moments such as when they receive their national insurance card (needed for paid employment) so that they can be brought into the electorate.

Controlling local election expenses

The UK has made major efforts to monitor and regulate the funding of electoral campaigns over the last 20 years. Yet the breaching of electoral laws became a more high-profile concern in the arena of campaign expenditure in 2015. Conservative MPs and their agents were accused of failing to account properly for campaign spending at the general election. The Tories claimed that they had abided by the rules as set out, and never intended to breach requirements. But the Electoral Commission found significant breach of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act (PPERA) and that the party demonstrated an ‘unreasonable’ lack of co-operation with the Commission. Cases from 14 police forces were referred to the Crown Prosecution Service, which eventually only decided to press charges in one case.

Yet these cases illustrated two concerning aspects of the regulatory regime. Firstly, charges were not pressed in many cases, not because the affair was trivial but because of ‘insufficient evidence to prove to the criminal standard that any candidate or agent was dishonest.’ It has been questioned whether the legislative framework requires such a high threshold of evidence, that it is difficult to prevent loose interpretations from parties. Secondly, there was a concerning effort and unwarranted from many to criticise and discredit the neutrality of the Electoral Commission, rather than accept the result, which will only undermine confidence in the electoral process in the longer term. A new concern is that different requirements in Northern Ireland provide a backdoor for influencing elections contests the UK.

‘Dark money’ and social media

As election campaigning increasingly shifts to the internet and social media new concerns have also been raised about how undisclosed ‘dark money’ can influence elections and undermine political equality. Political parties are reportedly increasingly making use of data analytics to track voter behaviour on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. This information can then be used to target advertisements in marginal constituencies. This involves a substantial investment of work and money in data analytics which does not necessarily fall within the UK’s short official campaign period. Nor does this kind of expenditure clearly fit within campaign spending categories that are regulated by law. Campaign advertising laws cover TV and radio, but not social media. The playing field at electoral contests may become increasingly uneven as a result, and there is a clear need for election finance arrangements to be updated for the digital era.

Reviewing Westminster constituency boundaries

During the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government the two parties reached agreement that the size of the House of Commons should be reduced from 650 to 600 MPs, and that the population sizes of constituencies would be equalised exactly, removing the tolerance for community and other factors that previously had meant that seats were only broadly of the same population size. There were still substantial variations between the smallest constituencies (often in inner city areas held by labour) and the largest constituencies (e.g. in fast-rowing suburban areas). The boundary review for Westminster elections was set in motion by the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act 2011. However, the Liberal Democrats subsequently withdrew co-operation on implementing the review, in response to Tory backbenchers wrecking House of Lords reform.

After the 2015 election brought a Tory majority again, fully equalised constituencies were revived. The Boundary Commissions published their proposals in the autumn of 2016. Following consultation, they will lay down the recommendations before Parliament by September 2018. But the calling of the 2017 general election meant that this would be likely to come into effect in 2022, rather than 2020. The ‘hung Parliament’ also means that implementation of the review may be postponed again to beyond the next general election. Any redrawing of boundaries creates costs for some individual MPs, even if their party benefits. Although most estimates suggest that the Conservatives would make perhaps 20 seat gains from 600 equal sized constituencies, some individual Tory MPs will also lose out and may not be keen on voting for their own seats to disappear.

Conclusions

Elections are an indispensable way for citizens to have popular control of government, and they are a fundamental foundation of political equality – two of the Democratic Audit’s guiding principles, set out by David Beetham. There is therefore significant room for improving electoral integrity so that these aims can be better achieved.

Political equality is certainly undermined by continued uneven levels of participation across groups, an antiquated and illogical electoral franchise denying people the right to vote in contests that affect them, and millions of people still being missing from the electoral register. There are also emerging threats to a level playing field in the area of political finance.

The paradox of Britain’s electoral democracy is that the most power to improve the electoral process resides with the victors from the electoral process – the government of the day. The Lords have flexed their muscles on key issues such as the franchise during the last Parliament and some amendments were passed. However, it is more difficult to have popular control of government, when the same government holds the power over reform of the electoral process. The ‘hung parliament’ may lead to compromises between parties and opportunities for greater cross-party consensus on electoral law legislation. However, it – and the workload deriving from Brexit laws – may also mean that the government introduces little legislation, and few changes are made.

This post does not represent the views of the LSE.

Toby S. James is a Senior Lecturer at the University of East Anglia and Lead Fellow on Electoral Modernisation to the All Party Parliamentary Group on Democratic Participation.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

One of the reasons why parties like UKIP were forced to turn to social media a decade ago is because of a factor your piece glaringly omits to make any mention of – the dramatically unfair nature of the way in which the free advertorial style coverage by state radio and tv is apportioned in the UK when diverse parties are banned from campaigning on tv and banned from spending enough to redress the balance.

In Britain actual political advertising is supposedly banned but what the state calls ‘the main parties’ are allowed almost limitless free advertorial style coverage every night during a campaign…while parties like UKIP were actually barred from access a lot of the time even when they were doing well in the polls, with organisations like the BBC using Orwellian ‘balance rules’ to only admit parties they wanted to admit. I myself was repeatedly edited out of hustings meetings when I stood as candidate for London Mayor and on more than one occasion the BBC asked organisers not to invite me as UKIP’s candidate to their events as it made things “difficult” for them to ‘edit’.

The endless media coverage, although tedious, tired and not worthy of the name journalism, has massive value in pure financial terms. One of the journalists who I had worked with in previous years told me that “we just go through the motions, we have to give the main ones equal coverage right down to the stopwatch and style of coverage, all monitored by the parties because they know the value, so it is lame and always subject to annoying interference by the parties and our lords and masters”. Go figure, as out American cousins would say.

As long as the state insists on censoring and suppressing parties from media coverage to keep it cosy, ways in the modern era will be found around it – unless we now plan to censor the internet, close down all social media for the campaign by making it a criminal offence to post anything about politics (like the days until the mid 50s when the BBC actually stuck to that govt rule!), and spend vast sums doing so.

The better way would be to actually embrace diversity and allow people to campaign. But you see precious little mention of that in articles about graphs and figures and ‘engagement’, and yet more attempts to tinker with the system…all of which go totally over the heads of 80% of the electorate.

Delighted to read an full analysis of our electoral system in terms of democracy.

The model used for assessing the strength of our democratic integrity, seems to be a collation of assessments against a list of requirements. It’s a bit like collecting the ingredients for a cake. If some ingredients are reduced, the cake can still be baked and eaten.

Academically this may be a strong model. But for me, (73, always voted and never had an MP represent me), the model doesn’t fit.

A more realistic model would be a linear system from civic education, registration, all the way through to fair voting systems, vote counting etc. If one bit of the chain is missing, the system does not work. For example, the registration might be perfect, the voting stations accessible etc., but it costs £50K to stand as a candidate. The results of the election must be null and void. So for me, and most others, we are effectively dis-enfranchised because of the first-past-the-post system. Not just a bit undemocratic – it’s not democracy at all. Dictatorships means that the people cannot get rid of a government. I voted to get rid of Thatcher, like most of us – and it didn’t work. The same with Blair. Now May and DUP.

Gerrymandering has become quite blatant in South Warwickshire for Stratford District Council (Conservative).

This is a very good overview of electoral integrity in the UK today.

Most electoral administrators are excellent, but some are not, sometimes due to council’s underspending and sometimes due to the competence of the people involved.

The independence of electoral administrators referred to is largely illusory: it is not an offence if local politicians, who are the day-to-day bosses of administrators, lean on them about the conduct of elections, and they do.

Dr James touches on the growth of “black money” in campaigns. This is becoming increasingly challenging, with the emergence of crowd-funding camapaigns against sitting MPs, notably Boris Johnson. Currently these seem to be funelling money into opposing parties, but we will see the emergence of crowdfunding to support negative social media campaigns against specific candidates. Electoral law is unprepared to regulate this.

Not just unprepared to regulate…they cannot regulate it without interfering with the internet or facebook or twitter or whatever. Electoral law designed to benefit the ‘main parties’ is under siege because those who control it are not doing it properly and are acting for the few. And as it was always corrupt (if even at times mildly so) then it is a good thing that diverse forces are forcing their way into the debate and not being suppressed by the state as they have been for so long. It will not be long before no-one really cares what these tired bodies say, as they will govern only a tiny part of the campaign (I mean, who actually really wants or needs party broadcasts any more, with their outdated length and with all the petty po-faced 1950s style state restrictions on them?)