Audit 2017: How democratic and effective is the interest group process in the UK?

Between elections, the interest group process (along with media and social media coverage) is a key way in which citizens can seek to communicate with their MPs and other representatives, and to influence government policy-makers. As part of our 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Patrick Dunleavy considers how far different social groups can gain access and influence decision-makers. How democratically does it operate, and how effectively are UK citizens’ interests considered?

A pressure gauge at the Kew Bridge Steam Museum. Photo: Tom Goskar via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence

This article was published as part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy. We have now published: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit with LSE Press, available in all ebook formats. You can download the whole book for free, and individual chapters, including a fully revised version of this article.

How should the interest group process operate in a liberal democracy?

• Elected representatives and politicians should recognise a need for continuous dialogue between decision-makers and different sections of the public over detailed policy choices. Procedures for involving interest groups in consultations should cover the full range of stakeholders whose interests are materially affected by policy choices.

• The resources for organising collective voice and action in pressure groups, trade unions, trade associations, non-governmental organisations, charities, community groups and other forms should be readily available. In particular, decision-makers should recognise the legitimacy of collective actions and mobilisations.

• The costs of organising effectively should be low and within reach of any social group or interest. State or philanthropic assistance should be available to ensure that a balanced representation of all affected interests can be achieved in the policy process.

• Decision-makers should recognise inequalities in resources across interest groups, and discount for different levels of ‘organisability’ and resources.

• Policy makers should also re-weight the inputs they receive so as to distinguish between shallow or even ‘fake’ harms being claimed by well-organised groups, and deeper harms potentially being suffered by hard-to-organise groups.

• Other aspects of liberal democratic processes, such as the ‘manifesto doctrine’ that elected governments implement all components of their election programmes, do not over-ride the need to consult and listen in detail to affected groups, and to choose policy options that minimise harms and maximise public legitimacy and consensus support.

• Since policy-makers must sometimes make changes that impose new risks and costs across society, they should in general seek to allocate risks to those groups best able to insure against them.

Between elections, a well-organised interest groups process generates a great deal of useful and perhaps more reliable information for policy-makers about preference intensities. By undertaking different levels of collective action along a continuum of participation opportunities, and incurring costs in doing so, ordinary citizens can accurately indicate how strongly they feel about issues to decision-makers.

So sending back a pre-devised public feedback form, writing to an MP, supporting an online petition to the government, or tweeting support for something indicates a low level of commitment. Paying membership fees to an interest group or going to meetings shows more commitment, and gives the group legitimacy and weight with politicians. Going on strike or marching in a demonstration indicates a higher level of commitments still. A well-organised interest group process will allow for a huge variety of ways in which citizens can indicate their views.

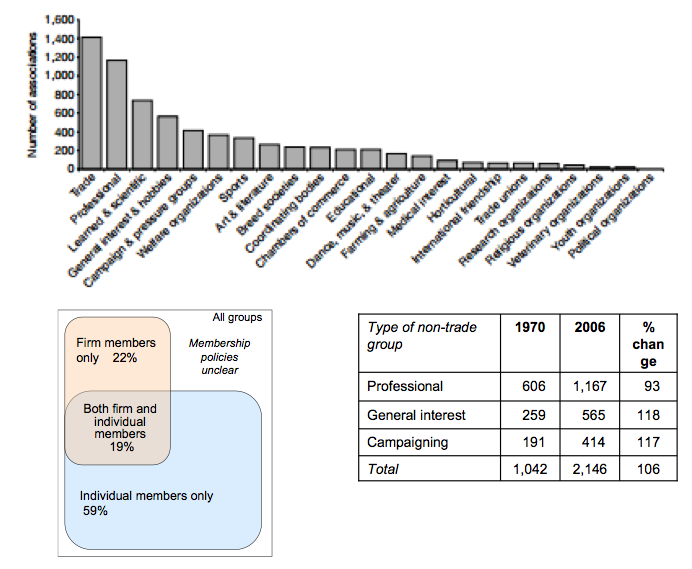

At any given time there are around 7,800 interest groups registered by directories for the field in 2009. Chart 1 shows some salient feature of the UK scene with multiple business trade associations (many very small), followed by professional and learned societies, and with campaigning and pressure groups fourth amongst the more specific types of groups. Some groups are very large – such as the UK’s trade unions, which have coalesced into a few very large membership bodies.

Chart 1: Key features of UK interest groups

Source: Jordan and Greenan, 2012, computed from pp. 82, 83, 92.

Four in every five interest groups recruit individual members, three out of five only recruit individuals – so their legitimacy is based quite heavily on their size. Those that can engage the participation of most people in a given occupation or role will carry especial weight, as with the well-organised medical professions. Over time the numbers of non-trade/individual membership groups has grown substantially, as the table part of Chart 1 show. Campaigning groups have grown slightly more in numbers than the general trend

A fifth of interest groups (all trade associations) only recruit firms as members, and a further fifth recruit both firms and individual members. Here legitimacy may be based on the proportion of an industry or a type of business engaged with a given body. There are often rather divergent voices claiming to represent business interests (as in the long-run rivalry of the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) and the Institute of Directors). Some industries are dominated by a single interest group, like the National Farmers’ Union, which achieves enormous insider influence with the relevant Whitehall department. Other looser coalitions of different interests (like the roads lobby of transport operators, construction companies and motorist organisations) can achieve a similar dominance, however.

At any given time, an ‘ecology’ of interest groups operates, with different organisations competing for attention, and encouraging their members to commit more resources or time to the group. Trade unions have been the biggest losers in recent decades, with memberships radically reduced by the decline of large firms, and even members in the public sector strikingly less willing to go on strike. Meanwhile environmentally aligned groups have flourished. Some big organisations that have shifted away from restrictive ‘legacy’ modes of recruiting members to digital approaches have increased their size radically, notably the Labour party under Jeremy Corbyn. But in the interest group world at large, such effects have generally been smaller.

Recent developments

This area of policy-making has been stable for many years, with occasional fringe scandals. Two small changes have taken place recently. The 2014 Lobbying Act introduced an official register of paid lobbyists operating with MPs in Westminster and in touch with Whitehall departments. But this was on a rather restrictive basis, affecting especially paid-for lobbying firms and some groups with developed governmental or parliamentary liaison operations. The lobbying industry (estimated by some sources to be worth £2bn a year) also remains self-regulated. For a period during the bill’s passage (2013-14), the Cabinet Office proposals seemed to threaten to make academics, universities and a wide range of charities advocating for policy changes register too. But after much criticism this proposal was fought off. However, the legislation is still somewhat controversial – particularly among charities, who complain that it stifles them before election campaigns.

The government has made a gesture towards digitally incorporating public views by re-establishing an official online petitions site in 2015, where citizens can lodge proposals for issues to be reviewed by Parliament. Any petition gaining 100,000 verified electronic signatures (a recently raided threshold) goes to the House of Commons and supposedly gets a debate, followed by a response. Very large numbers of petitions are started, but most quickly fail to attract public attention. Only those that can generate around 10,000 supporters in the first couple of days have any effective change of reaching the 100,000 limit in the time allowed. In 2016 thousands of petitions were started but only 10 reached the 100,000 limit, and four of these were denied a parliamentary debate.

However, these initiatives can be influential. In spring 2017 Theresa May invited newly elected US President Donald Trump on a state visit to the UK. A petition to ban him quickly attracted 1.86 million supporters. Although ministers said that they would ignore this, the idea of a visit quickly receded into the long grass after the 2017 election.

Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis

| Current strengths | Current weaknesses |

|---|---|

| British government ministers, MPs, politicians and civil servants recognise the importance and legitimacy of a vigorous interest group process. An open consultation process operates for all new legislation, and government policy White Papers, and sometimes for statutory instruments. | Where interest groups are battling against party A’s manifesto commitments, and especially where they are aligned with a rival party B, they will face an uphill struggle to make any changes in policies. Parties in government in the UK have a strong record of pushing through partisan commitments over-riding the opposition of groups who do not support them. The UK has no equivalent of the European Union’s formal reporting back of consultation outcomes. Ministers and civil servants will talk up any support their proposals secure and often ignore or belittle unfavourable feedback. |

| Parliamentary processes including the consideration of legislation, and questions to ministers, connect strongly with the interest group process. Most legitimate or established groups can find MPs to represent their interests or cause, or to help from their position in the legislature. Select committee inquiries access a more restricted range of ‘recognised’ interests. Public involvement processes in the devolved Scottish, Welsh, Northern Ireland and London legislatures are even more systematic and inclusive. | There are sharp inequalities in the capabilities of different social groups to monitor policy proposals and to get effectively involved in official consultation processes. The poorest and least socially resourced groups in British society rely chiefly on NGOs, charities and altruistic philanthropists to secure any research or campaigning on issues that concern them. By contrast, corporate interests have well-developed government and Parliamentary liaison units, and ready access to professional lobbyists, public relations consultants, marketers and media experts – giving businesses inherent advantages that are hard to counteract. |

| UK decision-makers are alert to the potentially excessive power of lobbyists and of well-resourced groups best able to afford lobbyists and other organized and commodified means of influence. Most (if not all) politicians discount heavily for the ‘industrialized’ lobby power of business and other wealthy groups. Lobbying is regulated and any excesses in attempting to secure influence are frowned upon and quickly stamped out. | Lobbying in the UK has historically focused most attention on private links with civil servants and ministers, exercised at early stages of the policy process, and often carried out without transparency. As the powers of the House of Commons have slowly grown, and coalition governments operated in hung Parliaments 2010-15 and 2017-present, so more lobbying has focused on the legislature. Because MPs and peers can work for outside jobs and take money from well-funded interests, there have been a succession of scandals around MPs, peers and even ministers not declaring interests. |

| For elected politicians, what matters most is the vote-power of groups, which is a function of their size (large membership groups are more influential than small ones), the intensity of their preferences (groups that care a lot outweigh apathetic ones), and their pivotality (giving more importance to potential ‘swing’ groups who might shift support between parties, shaping who wins). There are inherent influence inequalities between groups, but because they derive essentially from their role in the electoral process, they are generally democratically defensible. | For politicians the realpolitik of the interest group process is that they appease groups whose support they rely on. But they will cheerfully impose costs on groups normally opposed to them, or too small or poorly organised to do them electoral damage. Both ministers and civil servants also routinely extract a price for conceding influence to any ‘insider’ group. To remain influential the group must only express critical views ‘moderately’ and privately, at early stages of policy development before proposal go public. They must normally mute any public criticisms altogether, or tone them down to be non-confrontational or ‘responsible’. |

| Saturation media and social media coverage means that the risks for politicians in lightly or overtly deferring to powerfully organised interests have increased. Modern policy-making has shifted more into cognitive modes of competition between rival coalitions of interests. Here the quality of evidence you can produce to back a case, and effective participation in policy debates, count for more than simple voting power or financial might. A more deliberative interest group process has emerged, which has evened up access to the policy terrain. | Cognitive competition remains heavily influenced by resources and money. Wealthy interests can better afford to fund research and information gathering than groups representing the poor and powerless. Wealthy interests can also trigger more law cases in areas favourable to them and thus ensure that legal knowledge differentially develops in helpful ways. |

| Future opportunities | Future threats |

|---|---|

| The growth of social media and internet-based modes of organising has radically lowered the information and transaction costs of organising collective actions in the last two decades, and promises to continue doing so. In particular, large-scale citizen mobilisations by spatially dispersed or ‘functional’ groups have emerged. | Lobbying and public relations professionals have extended the techniques they deploy for well-funded interests to increasingly manipulate social media. A new and powerful ‘data-industrial complex’ has recently emerged, as the Leave campaign for the Brexit referendum aptly demonstrated. |

| The mass emergence of ‘clicktivism’ allows individuals to spontaneously signal their position on public issues on Twitter, Facebook and other social media. These ‘micro-donations’ of time and support mean that people get instant feedback on the popularity of their views and potentially linkages to like-minded people. This radically enhances the speed and granularity of the public’s collective vigilance over policy-making in liberal democracies. However, more critical citizen activist campaigners like Alberto Alemmano stress that clicktivism cannot be an end in itself, but must be part of a wide armouryof modernised citizen engagement leading to ‘real world’ engagement. | By increasingly ‘delegating’ the job of representing diverse interests to NGOs and charities, and restricting their own participation to digital means, well-educated and altruistic middle class people have just contributed to the further ‘professionalisation’ of democratic politics. Groups that slip between the gaps of NGOs concerns can lose out badly from this system. Their inexpert autonomous efforts to organise become ever more marginalised. |

| Crowdfunding via the internet has increasingly emerged as a way that large and dispersed groups can fund previously difficult mobilizations. For the anti-Brexit lobbyist Gina Miller used this technique to back anti-Brexit candidates in the 2017 general election. (However, her more famous Supreme Court legal case against the government was privately funded). Similarly, ‘open source’ techniques of organising can often help otherwise disadvantaged groups operate more effectively in competition with business hierarchies. | The virulent tone of the Brexit referendum campaign caused unhappiness among charities. The chief exec of the National Council of Voluntary Organizations said he regretted they had not spoken out enough because of fear of the 2014 regulations plus being pilloried in the media. In Brexit policy development so far, ministers and Whitehall have seemed reluctant to bring in outside voices, and groups have felt excluded, despite their EU expertise, according to Jeremy Richardson. |

| Interest groups are keen to get involved in the Brexit negotiations, not least because they know a lot about the EU policy process. |

‘Managing’ public consultations

Elections inherently give policymakers only a crude and infrequent idea of public opinion. Parties must aggregate issues together into programmes and manifestos. Citizens must each cast a single vote, with no capacity to indicate either which issue or policy commitment counts most with them. Nor can they express the different strength of their preferences on multiple issues. So even politicians with a clear manifesto commitment to implement have just a direction of travel, not a detailed route map for getting anywhere that works.

Public consultation processes (some linked to legislation or executive orders) generate huge volumes of very specific information about how and why different interests are affected by proposed policy changes, which will bear costs and which see benefits in them. Often the detailed information needed for effective policy implementation rests with trade associations, firms, trade unions, professions, NGOs, sub-national governments, or academia rather than in Whitehall. Hence in any policy area there will either be a ‘policy community’ that is strongly networked and perhaps pretty closed to regularly influential outsider groups; or a looser ‘policy network’, with more weakly tied or changeable sets of participants.

This may seem to leave Whitehall and ministers in a weak position, and some observers have rather fancifully described a ‘hollow Crown’ that has resulted. However, ministers and civil servants do not assign equal weight to all actors in networks, but instead demand ‘responsible’ behaviours from those to whom they will listen, such as think tanks, business lobbies, professions or expert academics. These ‘insider’ groups have the ear of policymakers, while more strident, public and ‘extreme’ voices are routinely discounted. Views from groups aligned with other parties than those in government may also be marginalised.

Finally, sophisticated opinion polling now allows both politicians and the public to regularly learn much more about how different types of citizen feel about issues – so the policy influence of public opinion as a whole has improved and magnified. And a lot of media and social media coverage and commentary ensures that policy-makers ‘get the message’ about which bits of their proposals are popular and with whom.

Corporate power in the interest group process

Yet is the apparent diversity and pluralism of the consultation process just a misleading façade? Vladimir Lenin famously argued that the liberal democratic state is ‘tied by a thousand threads’ into doing things that owners of capital want. But a concern about the ‘privileged position of business’ in dealing with government extends widely amongst liberal authors too, such as Charles Lindblom. Since businesses generate economic growth and taxes, they have special salience in making demands on politicians and officials. And as the journalist Robert Peston argued;

‘The wealthy will [always] find a way to buy political power – whether through the direct sponsorship of politicians and parties, or through the acquisition of media businesses, or through the financing of think tanks. The voices of the super-wealthy are heard by politicians well above the babble of the crowd…. We are more vulnerable than perhaps we have been since the nineteenth century to the advent of rule by an unelected oligarchy’ (p.346).

In a discussion of corporate power and financial sector dominance in the UK for Democratic Audit, David Beetham drew attention to how dominant corporate sectors in the UK economy first caused the 2008 economic crash by forcing through rash financial deregulation, but then were differentially rescued by unprecedented bank bailouts by the state, plus ‘quantitative easing’ by the Bank of England – which propped up the asset values of the wealthiest groups in society. Via transfer pricing, debt loading and shifting domicile the largest global companies have also effectively evaded corporation taxes and undermined the UK fiscal regime. Public disquiet and counter-mobilisations by online activists have dented this regime only in tiny ways (e.g. a consumer boycott forced Starbucks into ‘voluntarily’ paying nominal amounts of UK corporation tax).

Competition between ‘advocacy coalitions’

A more benign view of changes in the interest group process is given by the ‘advocacy coalition framework’ (ACF) view, which argues that the key influences on public policies now are cognitive ones. Old-style, ‘big battalion’ groups – like big corporations, media barons ands mass ranks of trade unions – sought influence on the basis that they could mobilise adverse votes at the ballot box or unfavourable coverage by media commentators. But most policy-level influence now comes from a different, cognitive competition process, one that is increasingly evidence-based and founded on research and understanding of society.

Nor are the battles that matter fought any longer by single interest groups, but rather by competing ‘advocacy coalitions’ that bring together clusters or networks of aligned groups on each side of the policy debate. For example, on tobacco policy a succession of nudge interventions by government followed up periodically by regulatory restrictions and new legislation have progressively strengthened the disincentives for smoking and curtailed ‘passive smoking’ in the UK. The apparently ascendant coalition here includes anti-smoking charities, the medical professions, NHS authorities, the health department in Whitehall, progressive local authorities who forced the pace of implementation, many non-smokers (especially those adversely affected by ‘passive smoking’, and so on. The coalition fighting a rearguard action includes of course the tobacco corporations front and centre, plus some other aligned businesses, pro-‘freedom’ or libertarian think tanks, Tories opposing a ‘nanny state’, and a diminishing minority of still enthusiastic smokers. Yet has the progress achieved in reducing smoking incidence over recent decades been fast and furious, or slow and often stalled? How you assess the scale and speed of these changes will shape how effectively you think cognitive competition changes the dynamics of group competition.

Conclusion

Nobody now claims that the UK’s interest group process is an equitable one. There are big and powerful lobbies, medium influence groups and no hopers battling against a hostile consensus. Democracy requires that each interest be able to effectively voice their case, and have it heard by policymakers on its merits, so that the group can in some way shape the things that matter most to them. On the whole, the first (voice) criterion is now easily met in Britain. But achieving any form of balanced, deliberative consideration of interests by policymakers remains an uphill struggle. Business dominance is reduced but still strong, despite the shift to cognitive competition and more evidence-based policy-making.

This post does not represent the views of the LSE.

Patrick Dunleavy is Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at the LSE and co-director of Democratic Audit.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.