Despite its anti-democratic agenda, Poland’s Law and Justice party still enjoys public support

The Polish Law and Justice party has governed for nearly two years. Its anti-democratic agenda has led to protests at home and criticism abroad. Kamil Marcinkiewicz (University of Hamburg) and Mary Stegmaier (University of Missouri) examine trends in party support in Poland and consider whether PiS still has a mandate to pursue its current course.

The Polish PM, Beata Szydło of PiS, thanks firefighters in 2016. Photo: Kancelaria Premiera. Public domain

Poland attracted international attention this summer when the parliament passed three bills that would have stripped the judiciary of its independence. Poles tookj to the streets in protest while the international community warned that these changes would undermine liberal democracy. Ultimately, the President vetoed two of the bills but signed the third, giving the government greater control of the lower courts.

This attempt to bring the judiciary under government control was the latest in a string of undemocratic actions taken by the governing Law and Justice (PiS) party. PiS came to power in October 2015 winning a majority of seats in the Polish lower house of parliament, the Sejm, despite winning just 37.58% of the vote. It also holds a majority in the Senate and the President hails from the party. This situation of unified government gives the PiS great power in passing legislation. The government has restricted freedom of assembly, transformed the public media into a PiS propaganda machine, crippled the Constitutional Tribunal, and increased political control over the civil service.

After two years of democratic backsliding and protests, does PiS still have the support it needs to pursue its anti-democratic agenda?

There are two dimensions to this question: support for the PiS and support for the opposition. To analyse them, we used polling data from May 2014 to the present. The voting intention polling data were compiled by Ewybory. (In total, we have 342 polls conducted over the past three years that ask respondents which party they would vote for in an election to the Sejm. Support for the 6 main parties is tracked: the governing right-wing nationalist Law and Justice (PiS), the centrist Civic Platform (PO), the liberal Nowoczesna (Modern), the right-wing populist Kukiz’15 (Kukiz), the socially conservative Polish People’s Party (PSL) representing farmers and the left-of-centre Democratic Left Alliance (SLD).

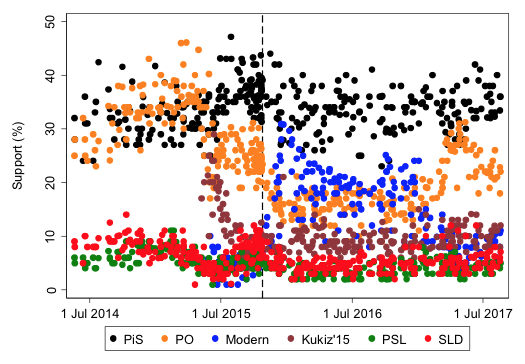

Figure 1 shows support levels in each of the polls separately. The dashed vertical line represents the parliamentary election. From this figure, it is challenging to discern clear levels and trends in support.

Figure 1. Polish party support mapped over time using 342 voting intention polls

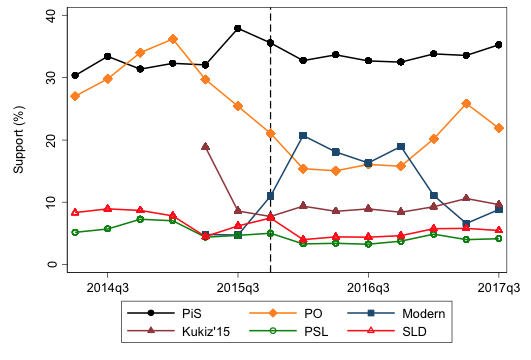

In order to get a clearer picture, in figure 2, we aggregate the polls by calculating average party support in each quarter. This strategy allows us to better observe levels and trends by averaging out the “noise” across polls conducted on different dates and by different firms. Also, because we are averaging a number of polls in each quarter, we are more confident in the estimated level of support than we would be if we were aggregating weekly or monthly.

PiS support has been remarkably stable over this time period, despite the party’s efforts to erode basic tenants of democracy. The spike occurring in the later quarters of 2015 corresponds to the parliamentary campaign and election (represented in the dashed vertical line). PO dramatically lost support in the same period of Modern’s rise, while the other 3 parties have had steady but low levels of support since the last election. Starting in early 2017, PO surpassed Modern to again become the dominant opposition party.

PO and Modern are the primary opposition to PiS and they are ideologically close. But, in the wake of the recent judicial crisis, the parties have been more explicit in their willingness to deepen cooperation and participate in the next parliamentary election together as one electoral coalition.

Figure 2. Average quarterly Polish party support over time

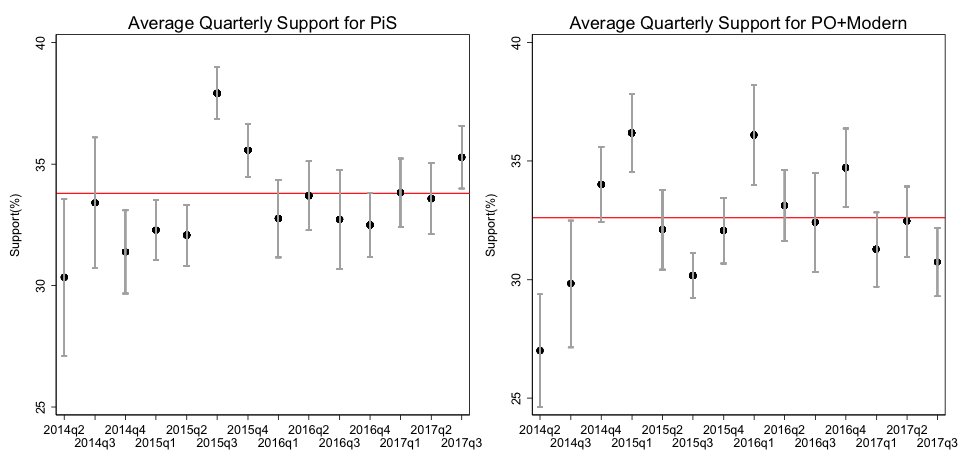

How does the level of support for the combined opposition, PO and Modern, compare with the support for PiS? One way to consider this is to compare the stability in their support.

Figure 3 depicts the average support for PiS and combined PO and Modern, over the entire time period in the horizontal lines. For each quarter we graph the level of support (with the dot) and the 95% confidence interval vertically around that.

PiS support has remained extremely stable over the past two years since the Sejm election. The long-term mean of 33.80% is located within the 95% confidence intervals for each of these quarters except for the current one. This contrasts with the liberal opposition. In the period after the election there were two quarters (Q1 and Q4 2016) when their joint support was significantly higher than the overall long-term mean. Then, in the current quarter, it falls well below the average value. We note however that we are only half way through Q3 of 2017, and thus, the party support estimates could change once polls for the entire month of September are available.

Figure 3. Average quarterly support with 95% confidence intervals compared to the long term average support.

The volatility in PO and Modern combined support, with a number of quarters significantly above or below the long term average, indicates that opposition supporters are not merely shifting support between the PO and Modern. Instead, figure 3 suggests that these voters are moving to and from other parties, or shifting between supporting the opposition and no party at all (non-voters).

PiS continues to enjoy popular support

The stability in PiS support, along with the volatility in the PO and Modern support, may allow PiS to stay its course. Neither the PiS’s past actions nor the recent protests have caused sustained shifts in voter preferences. The situation will not change much in the future. The presidential vetoes and August holidays effectively demobilised the opposition and helped the ruling party consolidate its electoral support. This is bad news for Polish democracy, since PiS may be emboldened to attempt to further tighten control over the judiciary and curtail media freedom. With stable public support, the ruling party also has little incentive to reach an agreement in its conflict with the European Commission.

The opposition, meanwhile, faces a problem. Its efforts to protect liberal democracy in Poland this summer did not attract new supporters. Yet, taken together, the electoral potential of the liberal opposition is comparable to the strength of PiS. PO and Modern could be more effective by not just forming an alliance, but cooperating more closely with civic groups that oppose the various aspects of the PiS agenda.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit.

Kamil Marcinkiewicz is a lecturer in political science and research methods at the University of Hamburg in Germany. His research focuses on voting behaviour, elections and parliaments in Poland, the Czech Republic and Germany.

Kamil Marcinkiewicz is a lecturer in political science and research methods at the University of Hamburg in Germany. His research focuses on voting behaviour, elections and parliaments in Poland, the Czech Republic and Germany.

Mary Stegmaier is an assistant professor in the Truman School of Public Affairs at the University of Missouri. Her research focuses on voting behaviour, elections, forecasting, and political representation in the Europe and the US.

Mary Stegmaier is an assistant professor in the Truman School of Public Affairs at the University of Missouri. Her research focuses on voting behaviour, elections, forecasting, and political representation in the Europe and the US.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

It would be difficult to write a more biased article. Stacking the Constitutional Court with 14 of its 15 members was fine … because it was done by the Rich Men’s Party, termed Liberals …