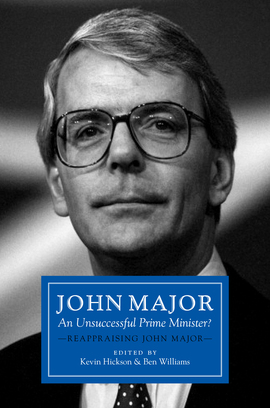

Book review: An Unsuccessful Prime Minister? Reappraising John Major, ed. Kevin Hickson and Ben Williams

In John Major: An Unsuccessful Prime Minister? Reappraising John Major, editors Kevin Hickson and Ben Williams offer a balanced reappraisal of the tumultuous years of the Major government, challenging perceptions of the former Prime Minister as simply an interlude between Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair. While the volume could have included more on the Major’s government approach to foreign policy, Robert Ledger praises this as a valuable addition to the historiography of late-20th-century British politics.

The Cones Hotline, which allowed the public to report the egregious use of traffic cones, was one of John Major’s less successful initiatives. Photo: Anthony Fine via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence

John Major: An Unsuccessful Prime Minister? Reappraising John Major. Kevin Hickson and Ben Williams (eds). Biteback Publishing. 2017.

It is now over twenty years since John Major left office as British Prime Minister. Often an outgoing administration’s reputation is miserable. This was particularly the case for the Major government, dragged down by a media onslaught, corruption and sleaze scandals, Conservative in-fighting over Europe and a public perception of economic incompetence. This stubbornly low standing – not helped by historians’ tendencies to view Major as an interlude between Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair – has only recently started to improve, in part following the 2014 and 2016 referendum campaigns, where he advocated long-held beliefs in statesman-like fashion and received significant – and mostly deferential – media coverage. John Major: An Unsuccessful Prime Minister? succeeds in providing a more balanced reappraisal of the tumultuous years of the Major government, repositioning him as an ‘honest, decent and competent Prime Minister’.

An Unsuccessful Prime Minister? provides a broad overview of Major’s premiership, covering a wide range of themes and policy areas. Some – such as sports, arts and the National Lottery – have received far less attention than others, like Black Wednesday or the Maastricht Treaty. The chapter on rail privatisation will be of particular interest for Britain’s frsutrated commuters, who may well reply negatively to the closing question: ‘Was it really worth the trouble?’ (193). Major’s instincts on this issue, to return to a ‘Big Four’ regional system, appear to have been a missed opportunity.

The Major government’s economic reputation was shattered after the humiliation of Black Wednesday in September 1992, forcing sterling out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). Despite Chancellor Ken Clarke’s safe stewardship of a growing, low-inflationary economy from 1993 up until New Labour’s victory in May 1997, the Conservatives were chastened for much of this period. As the book aptly details, much of this was due to the open civil war – fuelled by the media – that Black Wednesday catalysed in the Tory ranks. Despite Major’s skilful negotiation of the Maastricht Treaty (85), the subsequent ratification process emboldened a generation of Eurosceptics. The book also underscores some wider economic themes. Despite the windfall years of globalisation in the 1990s, the Conservative government struggled to deal with Britain’s long-term structural economic problems. The legacy of both the Conservative’s contortions over Europe and questions over the British economy’s place in a globalising world are, of course, still with us today.

A study of the Major years would not be complete without consideration of the Labour Party in the 1990s, particularly after Blair became leader. Here, the book tells a story of both confrontation and continuity. The amount of tax collected as a fraction of GDP declined between 1990 and 1997 (150). New Labour consistently criticised the state of Britain’s public services, a tactic that appeared to reap rich electoral rewards in 1997. For Major and Clarke, it was a ‘voteless recovery’ (157). The Major government was savaged by both the media and Labour for ‘sleaze’ and rising crime. Nevertheless, Major’s ‘Citizen’s Charter’ principles, as well as much of his education and health ‘choice’ agenda, were co-opted by the Blair government. The media environment of the era also looms large in the book. The sophisticated New Labour ‘spin’ operation that developed during the Major years, fuelling the flames of Conservative misery and shielding the Labour Party from similar damage, became a long-standing criticism of the Blair and Brown governments.

Major was a strong supporter of the union and wary of devolution in Scotland and Wales as a path towards separatism (56-57). This topic is discussed across several chapters and will provide readers with an interesting reappraisal from the retrospect of twenty years. The Northern Ireland peace process is another key policy area covered in some detail in An Unsuccessful Prime Minister?. John Major receives much praise for his role, and was willing to commit more political capital to this issue than virtually any other British Prime Minister, laying the groundwork for the 1998 Good Friday Agreement (138).

John Major’s tenure as Prime Minister coincided with a number of structural changes in British society. An Unsuccessful Prime Minister? contextualises the Major government in terms of these trends, including the acceleration of a globalised world economy and the liberalisation of social attitudes. In addition, much of David Cameron’s ‘Big Society’ can be seen in Major’s civic conservatism. Major was part continuation of Thatcherism, part gateway to New Labour, part ‘balancer’ during a testing period in British politics. Indeed, the book suggests he may have been the last ‘authentic’ Conservative Prime Minister (50).

John Major: An Unsuccessful Prime Minister? covers a wide range of policy areas in its 22 short chapters. As such, it works very well as an overview of the Major years, but can leave the reader wanting more on some topics. Foreign policy, for instance, is only touched upon briefly. The assertion in ‘An Overall Assessment’ that Major ‘was an equally steady and resolute leader over Bosnia’ (328) is highly contentious. Britain’s under-examined, and potentially catastrophic, policies towards a disintegrating Yugoslavia (as well as genocide in Rwanda) require further analysis and discussion. Although this is summarised well in the short chapter on foreign policy, at least another on this area would have been useful. Likewise, three short chapters written by other politicians of the era seem rather unnecessary. John Redwood’s self-satisfied ‘View From the Right’ in particular evades the balance found in the rest of the book.

In summary, John Major: An Unsuccessful Prime Minister? is an excellent addition to the historiography of late-20th-century British politics. It will appeal to the general reader, as well as to students and academics. Historians have skipped merrily from one hugely polarising figure (Thatcher) to another (Blair), paying only scant attention to the Major government. The current work on the 1990s often focuses on New Labour’s rise to power or provides memoirs and biographies, such as Anthony Seldon’s Major: A Political Life. This new book is a worthy addition to the still-developing literature.

This post represents the views of the auhtor and not those of Democratic Audit. It first appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Robert Ledger has a PhD from Queen Mary University London in political science, his thesis examining the influence of liberal economic ideas on the Thatcher government, and an MA in International Relations from Brunel University. He has worked in Brussels and Berlin for the European Stability Initiative – a think tank – on EU enlargement and human rights issues.

Find this book:

Find this book:

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.