Dual candidates running for the Welsh Assembly campaigned harder

There has been some controversy (and indecision) in Wales about whether National Assembly candidates should be allowed to stand for both a constituency and the regional list. Peter Hain argued it showed ‘utter contempt’ for voters, because someone who was rejected as an individual could nonetheless be elected. In the first two Assembly elections it was permitted, then banned in the subsequent two. In 2016 it was again allowed. Siim Trumm (University of Nottingham) analysed the campaigning style of the 2016 dual candidates and found they campaign harder and in a more balanced way than their rivals.

Leanne Wood ran for both the constituency of Rhondda and the South Wales Central regional list in 2016 for Plaid Cymru. The PC leader won both and the second candidate on the PC list took up her seat. Photo: Chwarae Teg via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence

The Wales Act 2014 reinstated the right of candidates to stand simultaneously as a constituency candidate and a regional list candidate for elections to the National Assembly for Wales. This seems to have paid off. Not only were dual candidates’ campaign efforts more intense and complex than those of their PR-only and SMD-only counterparts in the run up to the 2016 devolved election, but they were also the most balanced ones in their focus. Dual candidacy may have had to wait thirteen years to return to Wales, but there are reasons to hope it stays.

Mixed member electoral systems were the darling of late 20th century and early 21st century electoral engineers. Promising a balance between the proportionality and small group representation associated with PR and geographic representation of a particular locale and large, catch-all parties associated with SMD, mixed member electoral systems were seen as offering ‘the best of both worlds’. Not only did they become the electoral system of choice for many new democracies of Eastern Europe (and beyond) in the 1990s, they were also adopted in established democracies like Japan and New Zealand as a way of countering the popular disconnect with politics. The Government of Wales Act 1998 duly followed suit, opting for the Additional Member System as the way to elect the National Assembly for Wales.

So what is the fuss about? While Wales has kept faith with the Additional Member System, it has gone back and forth over whether dual candidacy – individuals permitted to stand as both constituency and regional list candidates – should be allowed or not. It was permitted in 1999 and 2003, banned in 2007 and 2011, but made a return once again in the 2016 election. It is a passionate debate, and one that we have most likely not heard the last of. Empirical evidence about the campaign behaviour of dual candidates, however, has been largely missing.

The 2016 Wales Candidate Study lets us compare the campaign behaviour of different candidates, including questions on their campaign effort, campaign activities used, and campaign style.

Campaign effort and diversity

First, I evaluated the intensity and complexity of candidates’ overall campaign effort. With regards to campaign intensity, it is measured in terms of time per week spent campaigning in the last month leading up to the election. With regards to campaign complexity, it is captured with an index that describes how many activities a candidate used in her campaign. Namely, it explores the extent to which candidates made use of canvassing, leafleting, media activities, calling up voters, street campaigning, debating in public, and online campaigning.

It becomes clear that, even when controlling for various individual-level characteristics, candidate type systematically influences campaign effort. I find that regional list candidates tend to carry out campaigns of lowest intensity and complexity, whereas it is dual candidates who spend most hours campaigning and use the widest range of campaign activities (Table 1). To illustrate this, I find that dual candidates are predicted to spend nearly 7 hours more per week on campaigning than constituency candidates (37.6 versus 30.9) and over 16 hours more per week on campaigning than regional list candidates (37.6 versus 21.5).

Dual candidates’ campaign effort is also most complex in terms of campaign activities used. The probability of carrying out a highly complex campaign – i.e., using all seven campaign activities – rises from 7.2% for regional list candidates to 15.3% for constituency candidates, and to 20.8% for dual candidates. On both indicators, the empirical evidence suggests that it is the dual candidates whose campaign efforts are most substantial.

Table 1. Campaign effort and campaign diversity by candidate type

| Campaign effort (hours) | Campaign diversity (Pr(7)) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Candidate type | ||

| Regional list | 21.5 | 7.2% |

| Constituency | 30.9 | 15.3% |

| Dual | 37.6 | 20.8% |

Campaign style

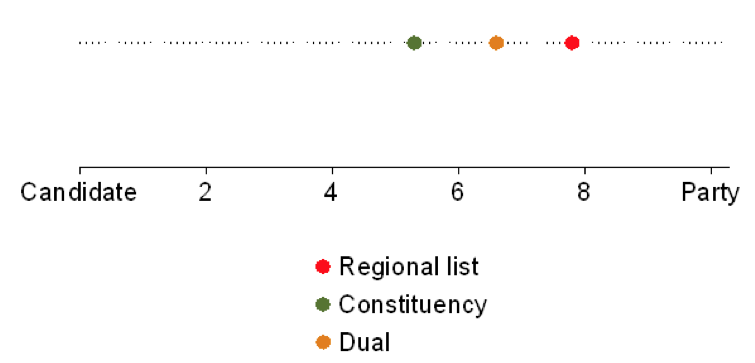

Next, I shed light on whether candidate type influences campaign style. I do so by using the survey question that asks respondents about the primary aim of their campaign, with the scale ranging from 0: ‘to attract as much attention as possible to me as a candidate’ to 10: ‘to attract as much attention as possible to my party’.

Candidate type has a systematic effect on campaign style even when controlling for various individual-level characteristics (Figure 1). The most candidate-centred campaigns are associated with constituency candidates and the most party-centred campaigns are associated with regional list candidates. At the same time, dual candidates’ campaign messages tend to be rather balanced; not as personalised as those of constituency candidates and not as partisan as those of regional list candidates. This pattern is clear when observing changes in predicted scores. They rise from 5.3 for constituency candidates to 7.8 for regional list candidates, with the predicted score for dual candidates being right in the middle at 6.6. Dual candidacy seems to promote a balanced campaign style.

Figure 1. Campaign style by candidate type

The best of both worlds?

Dual candidacy is certainly not without controversy when a part of mixed member electoral systems. For example, it does allow for the possibility of ‘losers becoming winners’, as candidates who lose their constituency races can still become Assembly Members on their party’s regional ticket. As such, there are normative concerns over whether dual candidacy should be allowed.

The empirical evidence, however, is clear about the benefits of allowing dual candidacy. It is the dual candidates who tend to carry out most intense and complex electoral campaigns. On average, they spend more time campaigning in the run up to the polling day and use a wider range of campaign activities than their PR-only and SMD-only counterparts. Running in two tiers at the same time does push candidates to campaign harder. What this of course means is that voters are likely to receive more electorally relevant information and are more likely to take note of it, as it is communicated to them through a wider range of channels.

Dual candidacy also tends to moderate the nature of campaign messages that voters receive, as dual candidates’ campaign focus is not as party-centred as that of PR-only candidates and not as candidate-centred as that of SMD-only candidates. This seems to be very much in line with what is generally seen as the key appeal of mixed member electoral systems – balance.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It first appeared at Ballots and Bullets.

Siim Trumm is Assistant Professor of Politics at the University of Nottingham.

Siim Trumm is Assistant Professor of Politics at the University of Nottingham.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.