Eleanor Mills: women are still portrayed through the lens of a male, pale and stale establishment

A new report by Women in Journalism, “The Tycoon and the Escort: The business of portraying women in newspapers”, shines a light on the extent to which British media offer a male-dominated interpretation of society. The title refers to the description used in the coverage of the murder by a businessman of his lover, which as the report notes “could easily have been the Failing Businessman and the Entrepreneur”. Sunday Times Editorial Director Eleanor Mills speaks to Tena Prelec about the findings of the study.

Eleanor Mills presenting the Women in Journalism report at the LSE. Photo: Nigel Stead/LSE

The report highlights the presence of a ‘male lens’ distorting the way women are portrayed in the British media. What are its consequences for society?

The fact that everything that women do is seen not through the gaze of other women, but through the gaze of a predominantly old, male, white middle-class elite, means that the media – rather than being a direct and true reflection of society – tell stories through a distorted lens. It is the lens of a very old, pale, male, stale establishment, who think that women should care about their appearance and that therefore they should be judged according to what they look like and not what they do.

Hence there have been episodes such as the infamous “Legs-it“, where we have Nicola Sturgeon and Theresa May meeting each other to discuss important matters for the country, and all the Daily Mail can say is ‘forget Brexit, what about Legs-it’. I think that sends a terrible message to women, communicating that however powerful they are, however clever, whatever they do, they will be judged by what they look like, rather than by the quality of their characters, how intelligent they are, their policies, and so on.

I think that this dynamic does come from a male lens on society and that it has a very negative effect on younger women considering to enter public life. I also think it restricts the idea of what women are capable of, and I find it massively depressing. I don’t want my two teenage daughters coming into a world where they think that all that matters about a woman is how good her legs are.

So what would be the equivalent of the Legs-it pun for men?

Rather than Brexit, we could have Package-it, with David Davies and Michael Barnier standing side by side. That’s indeed the equivalent, as they are being judged on sexual allure – it’s about the old question that Fleet Street seems to be asking about every woman they ever put in a paper, which is “Wouldya?”. This is what this is about – how hot are they.

This is particularly dangerous in an environment where, I think, misogyny does not go away – it only mutates. At the moment, we have a legal system according to which women’s rights are equal to men’s, but in the time that this has come about, over the last 20 years, we have had an absolute mushrooming of really violent and degrading pornography. It used to be a rather restricted activity, whereas today every man from the age of ten onwards has access to a wealth of pornographic material via the internet.

It strikes me that we have set up a culture where on the one hand we say that women are equal, women can do everything men can do, aspire and become leaders, but simultaneously we made widely available very degrading images, which communicate that women are there to be used as an object, to be degraded in every way a man can. I don’t think it’s an accident that, at the same time when women have become more powerful and more legally equal, what has mushroomed is this horrible porn culture, which implies that what really matters is how attractive women are to men. The fact that media operate through a ‘male lens’ means that this gets massively reinforced: a very patriarchal view is perpetuated, according to which women should be there to serve men, to be attractive, to be repressed, to have their biology controlled. I think that many people in our society don’t believe that anymore, but the media still does.

The report highlights that female authors tend to write on issues such as health, television, and the Royal family, with only few assigned beats such as politics, business, and even hard news – which in turn costs them the front page. Considering the high number of female politics graduates, what goes wrong in the process?

What happens, I think, is that the men hold onto the most powerful jobs for themselves. And, of course, reporting from Westminster is the most powerful job: you have extensive access to the most important people in the country, you are on first name terms with the most important politicians, you know the ministers. You even somehow become part of the government if you are in the lobby. Boys don’t really like to give that up. I don’t think it’s an accident that it has taken a female editor-in-chief, at the Guardian, to appoint two political editors who are women. There have been few female political editors before then, but predominantly it’s a boysy culture – as is the House of Commons, despite that optically women are now powerful in politics, as we have a female prime minister.

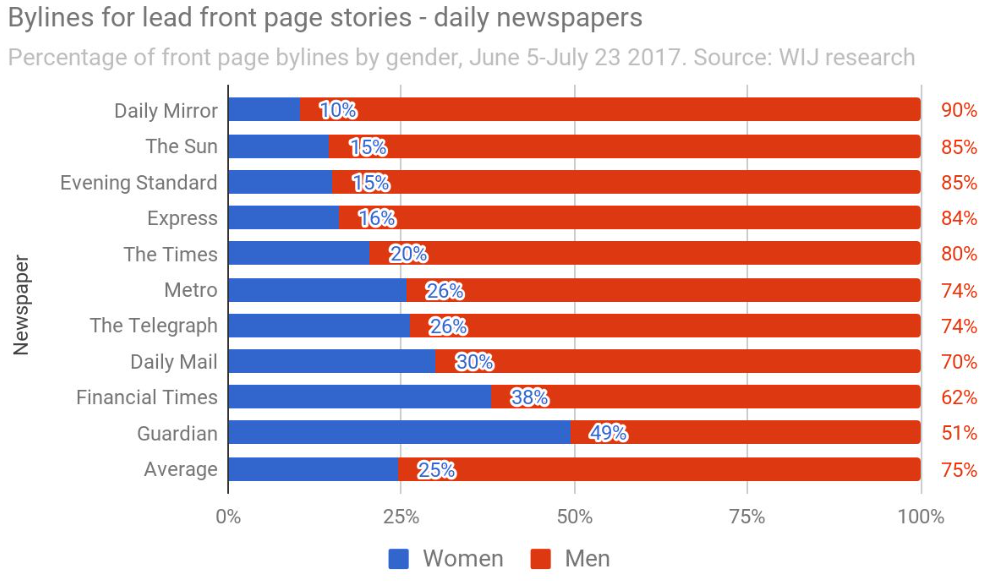

Source: Women in Journalism, 2017

Source: Women in Journalism, 2017

The Guardian is well ahead of all other mainstream British newspapers in terms of female involvement. How can other media follow in their footsteps?

They appointed a female editor, for a start, but more than that they really empowered her to make a change. There have been women who have been editors before, but always within a male-dominated system. Therefore, they haven’t changed things as much as they had wanted to, or maybe they didn’t even want to do so because they had become a part of the boys club in order to get there – they had become ‘honorary boys’.

The Guardian is quite different from other organisations as it doesn’t have an owner as such – it is run by the Scott Trust. Furthermore, it takes a particularly open culture to appoint two female political editors. When I worked at The Guardian and The Observer, I remember being told that they didn’t actually need any women in the meeting, because all the men there were so impeccably liberal, that they knew what women thought.

However, a left-wing environment can be just as misogynistic and antagonistic to women as anywhere else. I believe Jeremy Corbyn and Momentum really share an anti-women vent. So I don’t think that there is a left-right divide here. I think it’s good that the Guardian, which is a powerful voice, has a female editor. I think we need more female editors on Fleet Street, and we need a real acceptance within those newspapers that what they do matters. I feel passionately about that: I don’t think that the first draft of history should be only written by men.

What impact would you like this report to have on the British media scene?

I would really hope that any editor looking at this would take the point that it’s in their vital self-interest to broaden the diversity pool within the newsroom: you will get better stories, diverse points of view, and you will connect with the wider audience. Furthermore, you will be serving your function of holding power to account more effectively if you have different voices in the paper. We have to accept that the world has moved on, we no longer live in a completely patriarchal, white, caste and class society.

If the newspapers don’t do that, they will die. However, I don’t believe in quotas. What we do at the Sunday Times is to shine a light on what is going on, continue to monitor the situation and strive to broaden the diversity pool. But I also think that consumers will vote with their feet: if there aren’t enough women or enough diverse voices on the newspaper, they will stop existing, because they won’t be reflecting the world as it is.

Eleanor Mills was talking at the event The Tycoon and the Escort: The business of portraying women in newspapers, hosted by LSE Business Review. This post first appeared at LSE British Politics and Policy.

Tena Prelec is a doctoral researcher at the University of Sussex and co-editor of LSE EUROPP.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.