Do centre-right parties win back votes from the far right by talking about immigration?

With the rise of far-right parties in Europe during the 2000s, some centre-right parties spotted an opportunity to win back votes by pivoting towards immigration. James F Downes (Chinese University of Hong Kong) and Matthew Loveless (European University Institute) find that they were more successful if they were out of government at the time. Incumbent centre-right parties, on the other hand, struggled to cut through on the issue.

City council election posters in Middelburg, the Netherlands, 2014. The centre-right VVD tells residents Dauwendaele is for them, not for criminals. Photo: Wouter de Bruijn via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence

What has driven the resurgence of the far right in Europe? The broad consensus is that this ‘political earthquake’ can be explained by three key issues: concerns about immigration, dissatisfaction with the EU project and a lack of trust in mainstream parties.

At the same time, it is often assumed that the far right has monopolised and laid claim to the immigration issue from mainstream parties on both the left and right. But recent research by Sergi Pardos-Prado has demonstrated that, in fact, some centre right parties may have shifted their stances on immigration too, adopting a more anti-immigrant stance in order to counteract the threat from far right parties.

We argue that mainstream centre right parties are able to do this more effectively than the ‘party families’ on the centre left. There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, on immigration, centre right parties are closer spatially to populist radical right parties than centre left parties often are. In numerous cases – such as in the UK, the Netherlands and France – centre right parties have been ‘closer’ to radical right spaces, and have also made the issue salient in their party manifestos. When centre left parties have engaged with immigration, they have generally seen mixed electoral fortunes. Some scholars have also argued that centre left parties are more constrained on the immigration issue than centre right parties are, due to their internationalist outlook.

Arguably, immigration is directly linked to key centre right issues such as keeping taxation low and maintaining law and order alongside national security, and these are likely to appeal to a core base of the centre right electorate. The centre-right People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy in the Netherlands (VVD), for example, has pivoted on immigration before, having done so in reaction to the success of the far right List Pim Fortuyn in the early 2000s.

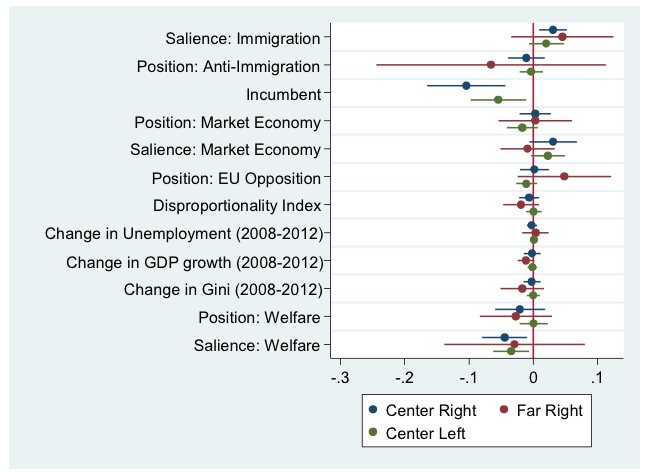

Centre-right parties recognised the 2008 economic crisis as a time of greater voter volatility (with an anti-incumbency effect), during which the populist radical right would try to secure more support through appeals to fears about immigration. Looking at parties’ electoral performances during the economic crisis in 24 EU countries (Figure 1), we found that specific centre right parties sought to respond with a ‘strategic emphasis’ on immigration in order to win over more voters.

While this effect is statistically significant, a closer inspection of the dataset showed that a specific ‘type’ of centre right party performed electorally better – namely ’challenger’ centre right parties that were not in government at the time of the economic crisis. Our results are also surprising because they depart from recent research that shows the importance of issue positions. Instead, our findings correspond to the issue salience model of voting, and the importance of centre right parties making immigration a salient issue in their party strategies, as opposed to adopting anti-immigrant stances. Tables 1 and 2 outline a summary of these specific cases below in more detail.

These ‘challenger’ centre right parties emphasised immigration and did better than, or at least ‘matched’, the electoral success of the respective far right party. Examples include centre right parties such as the New Flemish Alliance Party (N-VA) in Belgium, and the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy in the Netherlands (VVD). A number of centre right parties did not perform better during the economic crisis period. This happened particularly if (i) they were incumbents and punished in line with theories of economic voting (Union for a Popular Movement/UMP in France), or if (ii) they did not emphasise immigration (the National Coalition Party/KOK in Finland). Far right parties such as the True Finns in Finland and the Front National in France arguably prospered as a result. So there are limits on how useful emphasising immigration can be in economically tough times.

Figure 1: Regression coefficient plot with 95% confidence intervals (inclusion of control variables)

Source: Original Dataset on Change of Parties’ Performance in European National Parliamentary Elections and Rohrschneider–Whitefield Expert Survey.

Table 1: Centre-right and populist radical right party competition in the crisis period, by country and election years

| Centre-right outperformed far right (electoral success) | Centre-right and far-right competition (both achieved electoral success) | Far right outperformed centre-right (electoral success) | Centre-right performed better (countries without a far right party) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium (2007-10) | Netherlands (2006-10) | Finland (2007-11) | Spain (2004-08) |

| UK (2005-10) | Hungary (2006-10) | France (2007-12) | Portugal (2005-09) |

| Denmark (2007-11) | Sweden (2006-10) | Austria (2006-08) | |

| Italy (2006-08) | Greece (2007-09) |

Source: authors’ own

Table 2: Cases-conditions of centre right–far right party competition on immigration

| Country | C1: electoral volatility: centre-right incumbency punishment effect | C2: centre-right incumbents compete with far-right on immigration | C3: centre-right 'challenger' parties compete with far-right on immigration | Electoral outcomes ('winners') |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium 2007-10 | Yes | No | Yes | Centre-right 'challengers' |

| Netherlands 2006-10 | Yes | No | Yes | Centre-right and far-right challengers |

| Finland 2007-11 | Yes | No | No** | Far-right 'challengers' |

| France 2007-12 | Yes | Yes | No** | Far-right* 'challengers' |

Source: authors’ own

- * = denotes ‘relative’ levels of electoral success (i.e. increase in vote share, but did not translate into ‘significant’ seat gains.

- ** = denotes that there is no significant other ‘challenger’ centre right party in these countries.

The political scientist Herbert Kitschelt coined the phrase ‘electoral winning formula’ to describe the electoral success that specific radical right parties achieved in the 1990s by adopting neo-liberal economic positions alongside hardline positions on issues such as crime, law and order and immigration. Our findings suggest that during economic crises centre-right parties can win more votes by stressing immigration. Sometimes the centre right can even outperform the populist radical right electorally on this issue. Centre-right parties that were in opposition (such as N-VA in Belgium and VVD in the Netherlands) during economic downturns were not tainted by anti-incumbency effects, and therefore had more freedom to compete on the immigration issue with populist radical right parties. Further research should examine the strategies of both party families on immigration in the context of the ongoing refugee crisis.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit. It is based on a working paper, “Center Right and Radical Right Party Competition in Europe: Strategic Emphasis on Immigration, Incumbency and Economic Crisis”. Some of the materials in this article are also take from the author’s PhD thesis: Downes, James F. (2017) ‘A New Electoral Winning Formula?’ Beyond the Populist Radical Right: Center Right Party Electoral Success, ‘Strategic Emphasis’ and Incumbency Effects on Immigration in the 21st Century.’

James F Downes (Twitter @JamesFDownes) is a Lecturer in Political Science in the Department of Government and Public Administration at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is also an Affiliated Visiting Research Fellow (Honorary) at the Europe Asia Policy Centre for Comparative Studies.

James F Downes (Twitter @JamesFDownes) is a Lecturer in Political Science in the Department of Government and Public Administration at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is also an Affiliated Visiting Research Fellow (Honorary) at the Europe Asia Policy Centre for Comparative Studies.

Matthew Loveless is a Jean Monnet Fellow at the European University Institute.

Matthew Loveless is a Jean Monnet Fellow at the European University Institute.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.