Outside the south-east, Britain’s towns are struggling to hold on to their young people

Many of Britain’s towns are shrinking; big-city Britain is largely thriving. Taking south Wales as an example of these divisions, Ian Warren explains why his new Centre for Towns will advocate for the future of our towns, particularly during a period when both major parties in the UK parliament appear committed to city regions.

Merthyr Tydfil, 2014. Photo: Biggs via a CC BY 2.0 licence

Let’s consider the urban geography of south Wales.

In small towns across the Welsh valleys, terraced houses cling to hillsides in a landscape once dominated by a world-leading coal industry. Drive towards Cardiff, and you eventually pass through commuter belts with semi-detached or detached properties with one or two cars in the drive: they house young and middle-aged families with parents in well-paid employment. Arrive in Cardiff and you’re in a vibrant, modern university city of over 300,000 people, thousands of them students living across the city.

Nowhere else in the UK is there such a vivid example of the performance of the economic model which uses cities as the engine and driver of economic growth. The distance between the former coal mining communities of the valleys and the centre of Cardiff is around 25 miles. Yet the disparity in lived experience along the road from, say, Merthyr Tydfil to the Welsh Assembly building in Cardiff is a sharp reminder of how power and resources are concentrated in and around our towns and cities.

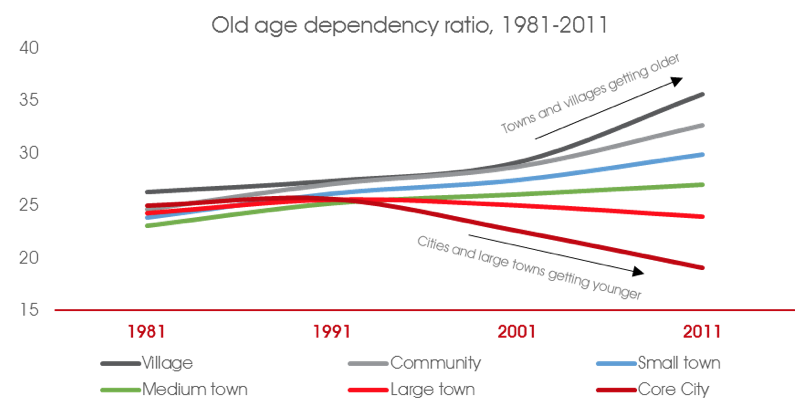

Over the last three decades, the population of the South Wales valleys fell while the population of Wales as a whole grew by around ten per cent. Merthyr Tydfil’s population fell by 4%; Ebbw Vale’s by 6%; Tredegar 7%; Tonypandy 11%. Perhaps more worryingly, it was the young people of those valley towns who were leaving. The population of under-25s fell by 18% in Merthyr; 22% in Ebbw Vale; 21% in Tredegar; 19% in Tonypandy. At the same time, and in the same places, the proportion of over-50s grew. Those places have aged markedly as a result. Old age dependency grew across the valleys.

The same wasn’t true for Cardiff; over the same period, the population of Cardiff increased by 25%. This growth was powered by young people moving to the city. The proportion of 16 to 24-year olds in Cardiff grew by 46% whilst the proportion of 25-44s grew at the same astonishing rate. The net effect is Cardiff and its commuter suburbs getting younger (and more prosperous) whilst the coal towns get older and older.

One outcome of this effect is seen in how each of these communities voted in the EU referendum. The road from Merthyr to Cardiff is a journey from Leave to Remain. The valleys voted Leave, in some places beating Remain by around twenty points. The commuter corridors were split evenly between Leave and Remain. Cardiff voted overwhelmingly to Remain. The valleys are a cognitive landscape of disaffection and anger which the EU referendum weaponised. It’s little surprise to me, by the way, that people at the other end of the Atlantic coal seam which appears in South Wales also found a medium through which to express their anger. Look it up: Appalachia voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump.

Not that this phenomenon is unique to Cardiff and the Valleys. Manchester voted to Remain but less than ten miles away the town of Oldham voted overwhelmingly to Leave. Liverpool chose Remain but 15 miles away the town of St Helens voted overwhelmingly to Leave. Newcastle and nearby Blyth displayed the same pattern.

Equally, the 2017 general election pointed to marked differences between how each of the parties performed in our towns and cities. Labour performed very strongly in university towns like Canterbury and Lancaster whilst the Conservatives performed better than expected in ageing former industrial towns like Mansfield and Middlesbrough.

In all those places, and more places besides, the trend holds. Towns across the UK are being emptied of their young people as they seek out better lives elsewhere. Over time, our towns get older. At present the two baby-boom echoes from the 1940s and 1960s, together with more recent inward migration, are holding the populations of the evacuated towns steady. But there’s a clock ticking. The baby-boomers will pass away, even as Brexit is likely to reduce levels of immigration.

This week the Centre For Towns explained this phenomenon by releasing new data showing how an ageing population is not evenly distributed across the United Kingdom, but that our villages, small and medium towns are getting older and older whilst our cities and larger towns are going in the opposite direction.

At the same time, in another important demographic sort, young professionals in their early thirties are leaving London and moving to commuter towns with more affordable housing in places like Canterbury, Luton, Crawley and High Wycombe. Almost 13,000 people moved from London to Luton in the last three years alone, whilst almost 14,000 moved to London to Canterbury. London is increasingly a staging post on a journey; young people from our smaller towns head to the city, graduate, gain employment and empty out into the rest of the south east.

The net effect of these demographic sorting events combined with an increasingly volatile electorate have powerful implications for our democracy. More importantly, they pose questions about the nature of our economic settlement. In the process of empowering city regions, are we simply increasing the speed of the escalator taking young people away from our towns? If so, what are we to do with the towns evacuated by those young people? These effects are not unique to the United Kingdom, but they do pose significant challenges for public policy. The Centre For Towns exists to respond to those challenges. Over the coming weeks I will emerge from my shed to release new data pertaining to the many thousands of villages, communities and towns in the Centre’s database.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

Ian Warren is director of Election Data, a consultancy specialising in election analysis, cartography and demographic segmentation. He has worked for all of the main parties, including at Labour HQ during the general election campaign. The Centre for Towns (Twitter @centrefortowns) launches in December 2017.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

” The population of under-25s fell by 18% in Merthyr; 22% in Ebbw Vale; 21% in Tredegar; 19% in Tonypandy. At the same time, and in the same places, the proportion of over-50s grew. ”

That only implies that the Valleys are “struggling to hold onto their young people” if you know young people are actually leaving. You’d get exactly the same results if people in the Valleys just weren’t having kids at replacement levels.

Let’s compare the Valleys with a Gloucestershire village or small town on the edge of the Cotswolds. You’ll see the same ageing of the population, but this time it’s because house prices have risen to be unaffordable for young people, many of whom would love to live there rather than in a van parked on Clifton Downs!

That picture is not Merthyr Tydfil.

Hello Ben. The picture is described as Merthyr Tydfil on Flickr, though it was taken in 1980, and perhaps I should have chosen a more recent photo. Can you identify the location? ^Ros Taylor