‘Gay’ or ‘homosexual’: the words we use can divide public opinion on civil rights

Words matter; different terms and phrases can have a huge influence on how the public thinks about important issues. For example, the term “homosexual” is more likely to be used to identify a group whom some feel are outside of society, while “gay and lesbian” are much more inclusive terms. In new research, Brianna A Smith and colleagues examines how these words can shape how people feel about civil rights policies. They find that compared to “gay and lesbian,” “homosexual” cues certain people to increase their opposition to civil rights policies that benefit gay men and lesbians.

Epitaph of gay Vietnam veteran Sgt Leonard Matlovich at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, DC. Photo: David via a CC-BY 2.0 licence

Language isn’t neutral. The words that the media, voters, and policymakers use can drastically change public opinion. For example, more Republicans disapprove of Obamacare than the Affordable Care Act – even though these are two names for the same policy.

Our research shows that important differences between the terms “homosexual” and “gay and lesbian” shape public opinion on civil rights policies. In a historical review of words used to describe gay men and lesbians, we find that the term “gay” has been used by advocacy groups to signal pride and acceptance of sexual identity. The more clinical term “homosexual,” on the other hand, has been used to pathologise and stigmatise same-sex desire.

The terms we use for sexuality matter because they signal group identity. “Gay and lesbian” is more likely to be used to describe friends, relatives, or neighbors. “Homosexual” is a strong marker of outgroup identity, or belonging to a group that is other from us and who live outside of our society.

Public opinion on gay and lesbian rights has changed a dramatically over time, but the divided use of the terms “homosexual” and “gay and lesbian” remains. As recently of August 2017, pamphlets in Australiaused the word “homosexual” to emphasize the supposed deviance of same-sex marriage ahead of a referendum on marriage equality. At the same time, positive coverage typically used “gay and lesbian” to describe the couples affected by the referendum.

What effect does this have on public opinion? We find that the word “homosexual” divides public opinion based on group identity. Compared to “gay and lesbian,” “homosexual” cues certain people to increase their opposition to civil rights policies that benefit gay men and lesbians.

We expect that people high in authoritarianism are more sensitive to language that signifies group distinctions. Authoritarianism is a personality trait which involves a greater desire for social order and conformity. Authoritarians keep outgroups at a distance in order to preserve this conformity. Past researchers tested whether authoritarianism alone increases hostility to “homosexuals” compared to “gays and lesbians,” but found mixed results.

The missing piece is that the perceived social order can differ from person to person. For some straight (or heterosexual) people, “homosexuals” are clearly outside of the norm; for others, so-called “homosexuals” are actually part of their social group. The word “homosexual” should most negatively affect the attitudes of authoritarians who also view gay men and lesbians as an outgroup.

Words matter when determining policy positions

To test this theory, we leverage a simple experiment contained within the American National Election Studies (ANES) 2012 survey. All participants were asked about their opinion on two civil rights policies affecting gay men and lesbians. However, for half of participants the policy questions referred to “homosexuals,” while the other half were asked about “gays and lesbians.” By comparing participants’ attitudes about the “homosexual” policy to participants’ attitudes about “gay and lesbian” policy, we are able to test whether the word “homosexual” cues group identity when determining policy positions.

We identify two factors that are associated with people’s perceptions of ingroups and outgroups. First, we directly measure whether or not people have lesbian, gay, or bisexual acquaintances. Second, our historical research shows that the word “homosexual” is often used in Born Again Christian churches to combat the cultural acceptance of gay men and lesbians. Because of this, we expect Born Again Christians to be more likely to view “homosexuals” as an outgroup.

Authoritarianism is measured using four hypothetical questions about parenting style. While these questions are not explicitly political, they do predict desire for conformity and hostility to outgroups. If our theory is correct, authoritarians who don’t know any gay men or lesbians, or who are Born Again Christians should be more hostile to policy that benefits “homosexuals.”

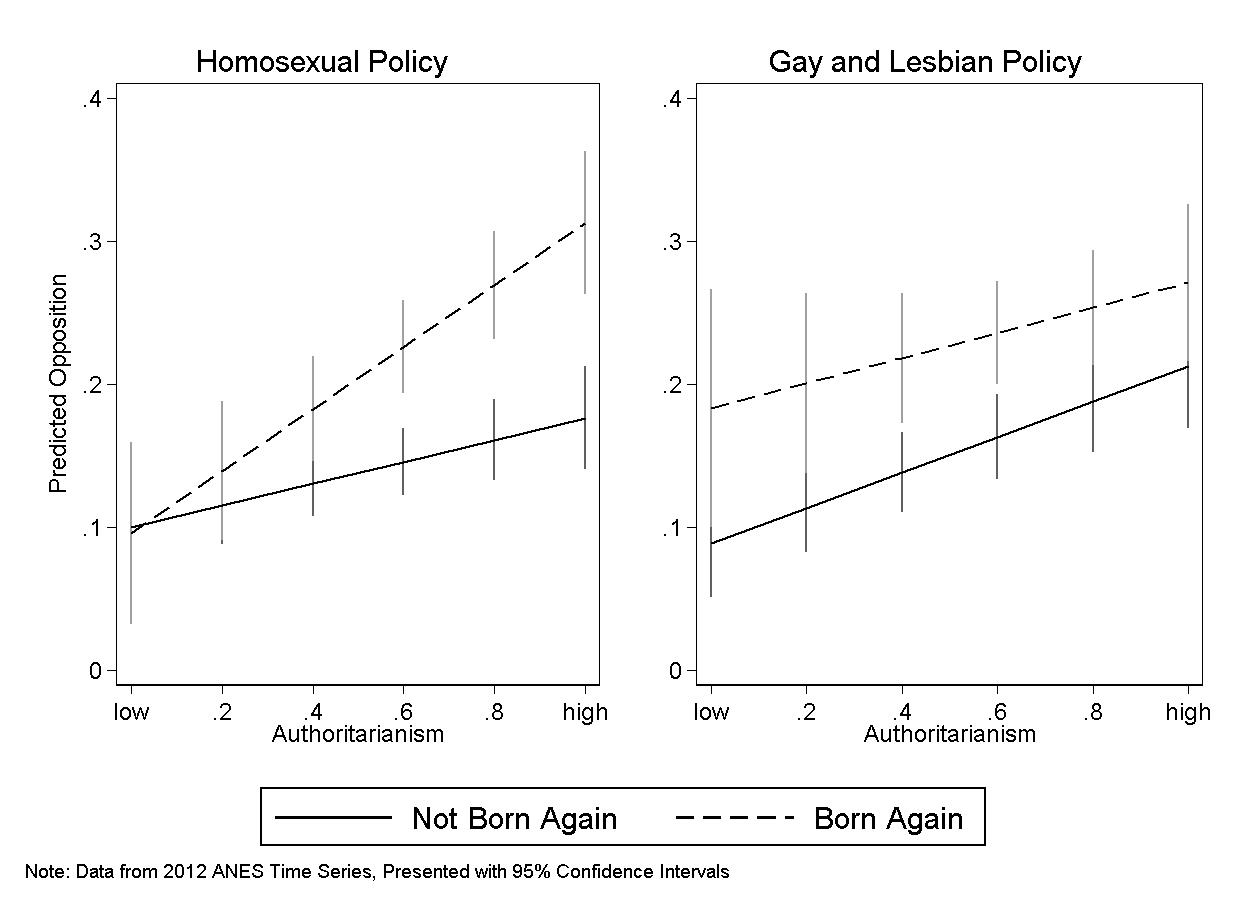

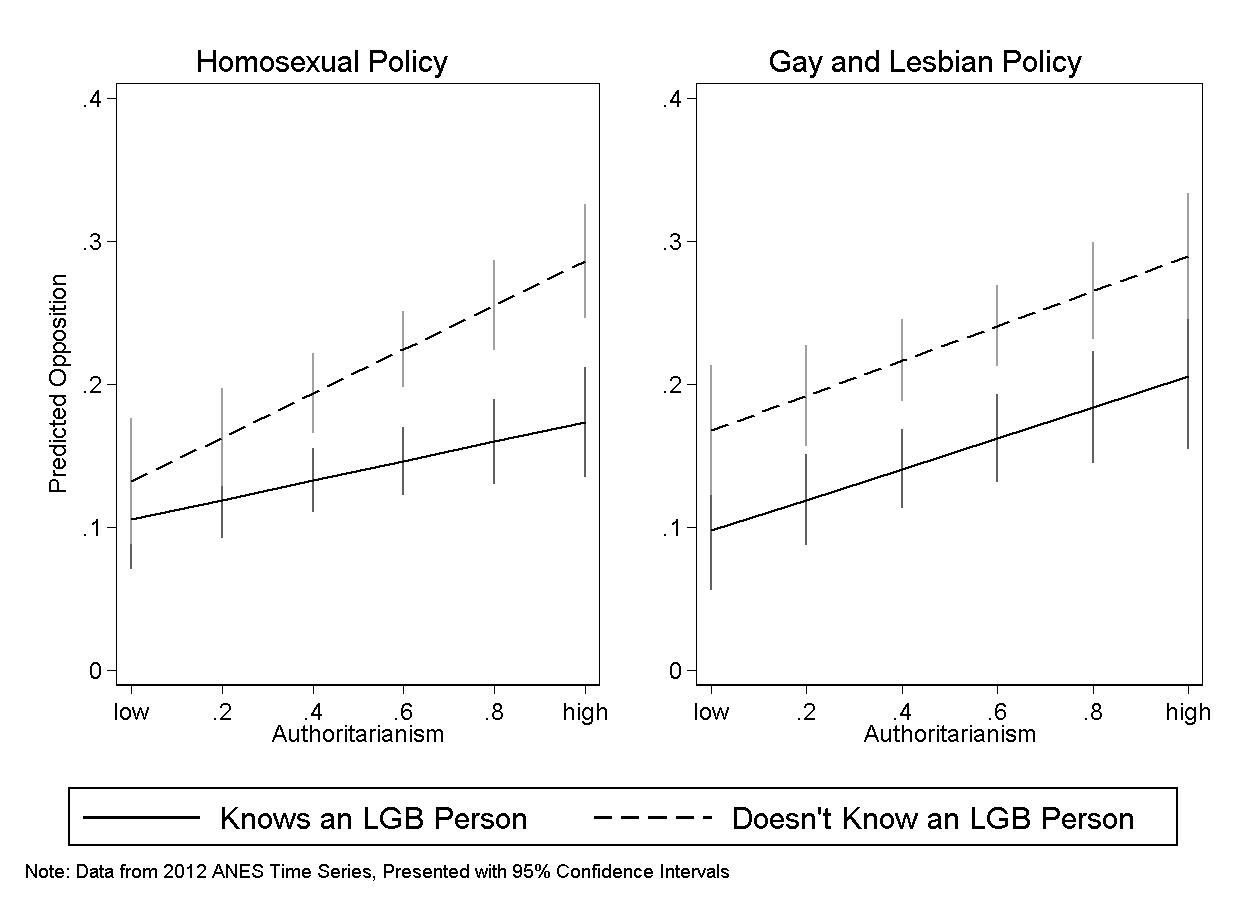

As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the results support our hypotheses. For instance, the effect of authoritarianism is almost 3 times more negative among Born Again Christians who were asked about “homosexual” rights than among those who are not Born Again Christians. Increasing from the lowest to the highest level of authoritarianism leads to a 21 percent increase in opposition for Born Again Christians, but only an 8 percent increase for everyone else. Having gay or lesbian acquaintances similarly interacts with authoritarianism– higher authoritarianism increases opposition to “homosexual” rights more strongly for those without gay or lesbian acquaintances. When a policy is described as benefiting “gays and lesbians,” however, group identity doesn’t affect authoritarian opposition.

Figure 1- Interaction between Born Again Christianity and authoritarianism, predicting opposition to “homosexual” or “gay and lesbian” policy

Figure 2 – Interaction between having lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB) acquaintances and authoritarianism, predicting opposition to “homosexual” or “gay and lesbian” policy

Our research shows that the use of the word “homosexual” divides public opinion. This language does not simply make everyone feel more negative about civil rights policy. Rather, it increases opposition among those who both view gay men and lesbians as an outgroup and are predisposed to dislike outgroups. For those who attach less importance to group divisions (i.e. low authoritarians), the use of divisive language may actually decrease opposition – perhaps because it reminds them of the existence of prejudice, which they wish to distance themselves from.

Nevertheless, a large portion of Americans are likely to react negatively to the word “homosexuals.” In our data, about twenty-two percent of people are high in authoritarianism and don’t know an LGB person. Twenty-three percent are both high in authoritarianism and Born Again Christian.

The words we use to talk about gay men and lesbians can shape public opinion. Policymakers trying to emphasise group divisions can do so by leveraging the word “homosexual.” For everyone else, “gay and lesbian” is a more neutral term which is less susceptible to opposition based on authoritarianism and group identity. By recognising the importance of language, we can communicate more effectively about policy and combat attempts to manipulate opinion and divide the public.

This article is based on the paper ‘“Gay” or “Homosexual”? The Implications of Social Category Labels for the Structure of Mass Attitudes’, in American Politics Research. It first appeared at the LSE USAPP blog.

Brianna A Smith is a PhD candidate at the University of Minnesota. Their research incorporates theories of psychology and decision making to better understand the complex ways people form political opinions and participate in politics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.