Book review | Know Your Place: Essays on the Working Class, by the Working Class

Inspired by the collection The Good Immigrant, Know Your Place: Essays on the Working Class by the Working Class brings together 22 stories reflecting on working-class lives and experiences in the UK today. Edited by Nathan Connolly, this volume offers tales of sadness, struggle, resilience and resistance, all told with warmth and love, that show how class inequality is both personal and structural, writes Lisa McKenzie.

Southend beach, 2010. Photo: Sludge C via a CC-BY-SA 2.0 licence

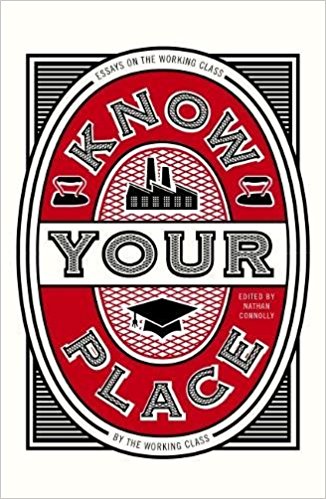

Know Your Place: Essays on the Working Class by the Working Class. Nathan Connolly (ed.). DeadInk Books. 2017.

As a child I was an avid reader. My local public library was a magical place that could transport me through time and into magical worlds that were far away from the small mining town in Nottinghamshire where I grew up. I read all of the C.S Lewis Narnia stories, and E Nesbit’s The Railway Children was one of my favourites. However, even at such an early age, I knew the children in these books were not like me: they were posh children, and their class position was obvious even at seven years old. They seemed as distant and as alien as the period of time they were written in. Growing up in the 1970s, I was used to reading children’s literature that didn’t really relate to me, about lives that I had no understanding of, language and a rhythm of speech I had no connection to at all. Although I think the foreignness of those stories were an attraction: they allowed me travel.

Stories and narratives have always been the most important things in my life, as they are for most working-class people, and in particular within working-class women’s lives. It is often working-class women that are the holder of stories, and then the tellers of them too. I remember sitting on my grandma’s knee and listening to times long gone in a language and rhythm that was so familiar I could see and hear those people in her stories. My favourite was the story about my grandad when he was a child: he was being laughed at and picked on by a bigger boy because he couldn’t read and write, but although he was small in stature, he could fight. My granddad’s name was John Reed and the other boy would sing, ‘Reed Reed, you can’t read’. His tormenter was a boy named John Badley; my granddad would sing back, ‘Badley Badley, I’ll knock you badly’. I loved that story: it was about sticking up for yourself and not being ashamed, a lesson that most working-class children learn throughout their lives and take with them into adulthood.

My great-grandma could read the tea-leaves and women would come in and sit around the small prefab bungalow she had moved into just after 1945. They would talk about what had gone before, about their children that had not had the opportunity to grow up and of their husbands that had been killed in mining accidents. Her own husband, my great-grandad, had died after he had a fight outside the pub on a Saturday night: he had fallen over and had hit his head on the pavement. These are the stories that working-class families pass down: they teach us about where we belong in the world, how we recognise each other, but also how we understand and recognise each other’s struggles; those stories are full of empathy, love and laughter. There is always an arc within these narratives; they are in fact perfect: they start slow but interesting; they engage the listener by acknowledging that we have something in common; we recognise behaviours, turns of phrases and situations; there is always an element of comic timing and there is always a purpose to those stories, life lessons.

Yet, unsurprisingly, very few of these stories have been written down and told amongst other working-class people who we do not have direct contact with. As I am writing this, the BBC are showing yet another version of EM Forster’s Howard’s End, more stories about bourgeois life that few of us connect with. We might argue that our stories, our working-class stories, are seldom told because their keepers traditionally did not have the adequate skills to write them down and have them published (my granddad’s story of standing up for himself is being told in print now for the first time). However, many of our stories are seen as too harsh or coarse, too rough, too sentimental or just too working-class.

The edited collection Know Your Place: Essays on the Working Class by the Working Class recognises all of these failures, not of working-class people but of a publishing industry that dismisses working-class experience as ‘common’ and ‘unremarkable’, and also of a wider society that considers working-class experience as being narrow, of little value or only as a prurient and salacious lens into debauchery, criminality and the ‘other’. Working-class lives, experiences and ultimately their stories are used too often as dialectical positions between the working-class hero, the victim or violent aggressor.

Know Your Place is not simply an edited collection of stories – it is much more important. The book was inspired by a tweet by editor of The Good Immigrant, Nikesh Shukla, and was then crowd-sourced: it happened because people supported it and acknowledged that without their support, it probably couldn’t have been produced in its current form (which is also a lovely object to hold in your hands). Know Your Place is a book that is a political howl from those who know that it is easier, that we are easier, to go unacknowledged and that our experiences, our lives, our humour are difficult for others to take. The essays, written by 22 contributors, span wide-ranging issues that affect all of society, including sexuality, gender inequality and race. However, all are written from the perspective of first-hand experience, showing clearly and arguing from beginning to end that class inequality is both personal and structural.

The editor, Nathan Connolly, has described the book as a ‘cultural response to a populism that is left at the feet of the working class without giving them a voice in return – making them scapegoats’. I agree with Connolly, and the book is such an antidote to the stories that are told about us. I really want to pull out one or two stories but I can’t: I actually love them all. Tales of the British seaside as a first-generation immigrant; I love every (and there are many) stories about the importance of the ‘chippy’; there are stories about the sadness and the struggle, about resilience, resistance and rage, but all of them are wrapped in a warmth and in love. In other words, it’s one of those books that you have to read for yourself and not rely on the review.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It first appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Dr Lisa Mckenzie is a working-class academic, currently a lecturer at Middlesex University in Practical Sociology and an Atlantic Fellow at the Inequalities Institute working on projects relating to class, gender and spatial inequality.

Find this book:

Find this book:

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.