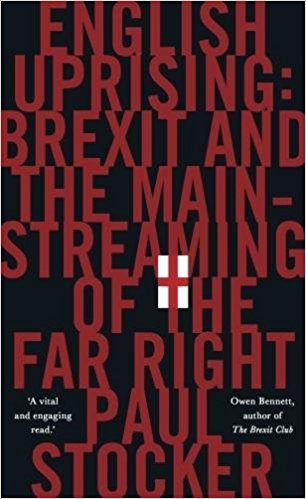

Book Review | English Uprising: Brexit and the Mainstreaming of the Far Right by Paul Stocker

In England Uprising: Brexit and the Mainstreaming of the Far Right, Paul Stocker offers a historical account of the rise of far-right movements in the UK from the early twentieth century to the present, showing how the gradual mainstreaming of far-right discourse impacted upon the recent UK Brexit vote. This book is an excellent primer for those looking to understand the changing influence of the far right on modern British politics, writes Katherine Williams.

Image Credit: Socks of Nigel Farage, former UKIP leader, 8 November 2017, Web Summit 2017, Lisbon (Diarmuid Greene/Web Summit via Sportsfile CC BY 2.0)

English Uprising: Brexit and the Mainstreaming of the Far Right. Paul Stocker. Melville House Books. 2017.

England Uprising: Brexit and the Mainstreaming of the Far Right, written by Paul Stocker, (Centre for Fascist, Anti-Fascist and Post-Fascist Studies, Teesside University, UK), traces the rise of far-right movements in the UK from the early twentieth century until the present. Alongside this, the book also explores how the steady proliferation of far-right discourses within recent years has influenced public attitudes towards the European Union, resulting in Brexit.

As Stocker notes in the introduction, Brexit came as a big shock to many in the UK. However, the historical context behind the vote, discussed at length throughout the book, suggests something entirely different. Brexit, the author argues, is symptomatic of wider political strife that is not only engulfing Europe, but also the US, particularly following the election of Donald Trump. These two events evidently represent the profound discontent many people feel with political elites, both at home and further afield. The vote for Brexit reflects a growing divide within British society, along both demographic and cultural lines.

Whilst far-right groups and ideologies have traditionally existed at the fringe of British politics, the growing mainstreaming of their ideas has led to them being co-opted by centrist political parties. Stocker notes that politicians in the Labour and the Conservative parties have adopted the language of far-right anti-immigration sentiment: the Conservatives’ ‘Go Home’ van scheme being a case in point as well as the scandal surrounding Labour’s ‘Control on Immigration’ mugs. Broad public acceptance of the UK Independence Party (UKIP) has also meant that nationalist and anti-immigration rhetoric is not the taboo subject many may have considered it to be.

The focus of this text is primarily historical, and it aims to expose and then understand the root causes of Brexit. Stocker points out that whilst there is significant discussion dedicated to the far right and fascism throughout, it is not his intention to paint all those who voted ‘Leave’ in the UK EU referendum as extremists. Nonetheless, the book is comprised of eight chapters which chart the rise and fall of far-right groups and their various ideologies in the UK. This review shall focus on two of these chapters: Chapter One, ‘A History of Intolerance’, and Chapter Six, ‘Take Back Control: The EU Referendum’, which together give a good sense of Stocker’s perspective on how it all began and the consequences for today.

In Chapter One, Stocker states his belief that Britons have an ‘amnesiac view’ of immigration which does not accurately reflect historic precedent. Guilty of seeing the world through rose-tinted glasses, this means that not only are the crimes of the British Empire forgotten by UK citizens, but also Britain’s historically less-than-welcoming attitude towards immigrants. By examining the UK’s longstanding relationship with migration, the author exposes ‘themes’ still seen today. In his discussion of Irish migration to Britain after the Great Famine, for example, Stocker notes that the UK media began depicting the Irish migrants in dehumanising ways, as this 1847 extract from The Times illustrates:

‘Ireland is pouring into the cities, and even into the villages of this island, a fetid torrent of famine, nakedness, dirt, and fever […] the ports of Wales are deliberately invaded by floating pest-houses…’

Much of the same vitriol would be levelled at Jewish migrants arriving in the UK between 1881-1914. Such examples are not too dissimilar from the rhetoric employed by media commentators discussing the recent refugee crisis: for instance, Katie Hopkins writing in The Sun:

‘NO, I don’t care. Show me pictures of coffins, show me bodies floating in water, play violins and show me skinny people looking sad. I still don’t care […] make no mistake, these migrants are like cockroaches.’

It is in the early post-World War I period that the origins of the far right can be located. Whilst Britain had considered itself on the winning side, many felt disillusioned about the UK’s place in the world and its rapidly declining Empire. Fascism first emerged in Italy following WWI, and soon there was a British equivalent: the British Fascisti (BF), formed in 1923. The author notes that the BF’s ideology reflected an emerging authoritarian, anti-communist, anti-Semitic political movement; this was combined with ideas regarding imperialism and white supremacy. The British Union of Fascists (BUF), founded by Oswald Mosely in 1932, would continue in this tradition, despite their attempts to intellectualise their discriminatory political ideology.

There was significant migration to the UK following the British Nationality Act (1948). Despite the demand for workers following World War II, discrimination against commonwealth workers often went unchallenged, and groups soon found themselves accused of undercutting wages amongst other transgressions. However, demographic changes resulting from commonwealth migration were not the cause of far-right mobilisation: they simply exacerbated existing political divisions.

The far right at this point consisted of very small and decidedly ‘eccentric’ organisations, according to Stocker. This would soon change with the founding of the National Front (NF) in the 1960s. Subsequent groups such as the British National Party (BNP) reached ‘unprecedented heights’ in 2003’s local elections, securing seventeen per cent of the average vote and thirteen council seats. Despite their relative electoral success and attempts to modernise, the BNP could not quite shake off their association with fascism, particularly after BNP leader Nick Griffin’s appearance on BBC Question Time in 2009. However, as the author notes, the collapse of the BNP did not necessarily represent a victory for those on the left; it was rather a rejection of a party with too much ‘fascist baggage’. Where the BNP failed, UKIP brought far-right ideologies in from the margins to the political mainstream, positioning the immigration debate at the heart of their anti-EU campaigning.

In Chapter Six, Stocker shows how the anti-immigration politics of political parties such as UKIP have become increasingly normalised. Then-leader Nigel Farage was invited to televised political debates, at one point suggesting banning HIV-positive migrants to the UK. Events including the Charlie Hebdo and Bataclan terrorist attacks in France and even the Greek banking crisis led Nigel Farage to claim that multiculturalism had failed. UKIP ending up winning 3.9 million votes in the 2015 General Election: this would have equalled 80 seats under Proportional Representation, but under the current system, it meant just one.

As with the General Election of 2015, immigration became the central focus of the 2016 EU referendum, with attention shifting away from economic issues; the Leave campaign was soon being fought along racialised lines. Farage and other prominent Brexiteers did little to assuage public misconceptions surrounding immigration and the UKIP leader was accused of inciting racial hatred after unveiling an anti-migrant poster that appeared to suggest that migrants and refugees were flooding UK borders. This, claims Stocker, would go down in infamy as ‘the most inflammatory exploitation of immigration and the migrant crisis during the EU referendum’.

Rhetoric, as history has shown, has consequences. On the same day that the ‘Breaking Point’ poster was unveiled, Labour MP Jo Cox was murdered outside of her constituency surgery. Undoubtedly targeted because of her commitment to the ‘Remain’ campaign and her advocacy of migrants’ rights, her attacker, right-wing extremist Thomas Mair, was heard to shout ‘Britain First’ as he shot and stabbed Jo Cox and grievously injured staff and onlookers who had tried to help. Later, after it was clear that Britain had voted to leave the EU, Farage made the bizarre claim that Brexit had been won ‘without having to fight, without a single bullet fired’.

England Uprising is an excellent primer for readers who may not be particularly familiar with the debates surrounding Brexit and the influence of far-right rhetoric and politics on contemporary British politics. Stocker’s notion of ‘mainstreaming’ adds to our understanding of the increased presence of far-right discourse and ideology in modern political life. And where do we go from here? It is hard to speculate at this point, but the author warns readers not to become complacent with this supposed new ‘normal’, positing that Brexit is, in fact, part of a historical process by which far-right groups have maintained a constant presence on the fringes of British politics.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It first appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Katherine Williams is an ESRC-funded PhD candidate at Cardiff University. Her research interests include the role of women in far-right groups, feminist methodologies and political theory, and gender in IR. You can follow her on Twitter: @phdkat. Read more by Katherine Williams.

Find this book:

Find this book:

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] her review of England Uprising: Brexit and the mainstreaming of the far right, Katherine Williams summarises the book’s history of the far-right movement as the historical […]