The Lords are unlikely to derail or overly delay the passage of the EU (Withdrawal) Bill

Richard Reid explains why the House of Lords is unlikely to derail or overly delay the passage of the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill that is about to be introduced into the Chamber. He contends that while the mood of the House regarding Brexit is difficult to tell, it seems that there is little appetite for a direct collision with the government in the form of blocking or wrecking the bill. However, we are likely to see some successful amendments regarding the acquis, devolution and Parliamentary sovereignty that will win support from across the party groupings.

The House of Lords, Queen’s Speech. Picture: UK Parliament via (CC BY-NC 2.0)

On 30 January the House of Lords will begin its scrutiny of the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill. The Bill arrived from the Commons on Thursday 18 January for its first reading in the Lords. The approach of peers to this bill is as yet uncertain and may become clearer during the second reading. However, in a previous report for the Constitution Society, I outlined three areas where Lords’ committees have expressed concern over the bill as it stood, prior to amendment during its progress through the Commons. These are also areas where new amendments are now possible:

- the degree and method of incorporation of the EU acquis;

- the powers and competencies of the devolved administrations; and,

- the relationship between Parliament and the executive.

There were some amendments to these areas in the Commons, but there is still likely to be much of concern to the upper House. One peer David Hannay (a former UK Permanent Representative to the EU) outlined the areas he thought of most concern:

the Henry VIII powers being sought by the government, the handling of devolved powers when they are repatriated, the inclusion of the EU’s Human Rights Charter in our domestic law (which the government does not want), provision for a transitional period (which the government appears to accept) and for legislative changes required by the outcome of the Brexit negotiations (on which the government is now promising a separate piece of primary legislation), and, last but not least, the entry into force of provisions for the Act, once passed, which is our old friend the ‘meaningful process’ for approving a deal (or no deal).

These comments were made in early December 2017, before Dominic Grieve’s amendment passed in the Commons dealing with the ‘meaningful process’ issue, but not the ‘no deal’ scenario. Yet they still provide a fair assessment of the main areas of possible concern for peers.

The mood of the House is difficult to tell, and there is naturally a degree of crystal-ball gazing involved in considering the Lords likely approach to Brexit. It seems that there is little appetite for a direct collision with the government in the form of blocking or wrecking the bill. However, there are likely to be some successful amendments in the areas outlined above that will win support from across the party groupings. These amendments are likely to be designed to be taken up by the Commons if they so desire, a scenario foreshadowed by some MPs as the bill left for the Lords. If the government is able to overturn the Lords’ amendments in the Commons, it remains unclear how hard peers are likely to push these amendments in the ping-pong stage. Whether any amendment is successful is going to depend in large part on the approach of the Labour benches.

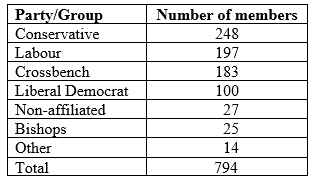

At present the Conservative party have the largest grouping, followed by Labour, the Crossbench and the Liberal Democrats with 100 peers (see Table 1). The Crossbenches rarely vote en bloc (although persuasive crossbenchers can bring with them supporters). So if the Crossbenchers are divided, and if the Liberal Democrats and the Labour party are not, they will be able to defeat the government. So the approach of the Labour benches will be crucial to the success of amendments. Labour is clearly not immune from internal disagreement on Brexit; however, there is normally a high degree of party cohesion amongst the party groups in the Lords.

Table 1: Current membership of the House of Lords

Source: House of Lords

Of course, the most important external influence is public opinion. If public opinion moves against Brexit as the process develops, then all bets are off as to how the Labour party is likely to approach the question. But as things stand both the government and the Labour party are still publicly committed to delivering Brexit. That said, a recent debate in the Lords on the report Brexit: deal or no deal from the House of Lords European Union Committee demonstrated the strength of feeling in the House. Its tense and heated tone is likely to be repeated in the Lords during the progress of the Withdrawal Bill.

Ultimately, however, the House of Lords is unlikely to wreck or overly delay the passage of this Bill. It is seen as more a question of process rather substance, because further legislation, including an ‘implementation bill’, will be introduced at a later stage in the Brexit process.

The article gives the views of the author, and not Democratic Audit. It was originally published on LSE Brexit.

About the author

Dr Richard Reid is an Associate Member of the Gwilym Gibbon Centre for Public Policy at Nuffield College, University of Oxford, and Europa Visiting Fellow at the European Studies Centre in the Australian National University.

Dr Richard Reid is an Associate Member of the Gwilym Gibbon Centre for Public Policy at Nuffield College, University of Oxford, and Europa Visiting Fellow at the European Studies Centre in the Australian National University.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.