Increasing ethnic minority representation: why both political parties and electoral districts matter

National parliaments in Western democracies remain far whiter than the increasingly diverse populations they represent. Benjamin Farrer (Knox College) and Josh Zingher (Old Dominion University) find that the explanation for this lies in the interaction of local demographics and political parties, and that as a result centre-left parties in the US, UK and Australia have been more successful at getting ethnic minority candidates elected.

BAME rally in support of Jeremy Corbyn, 2015. Picture: Steve Eason, via (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Nearly every Western democracy is becoming more ethnically, racially and religiously diverse. This increasing diversity raises a number of important questions as to how emerging groups will be incorporated (or not incorporated) into democratic systems. There is a significant body of research that suggests recent immigrants and other minority groups have become increasingly engaged as voters. In many countries ethnic minority voters have become a key constituency, especially for centre-left parties. However, this increasing propensity to vote has not been met with a corresponding increase of ethnic minority legislators. One feature that is common to virtually every Western democracy is a national legislature that is far whiter (not to mention older and more male) than the country’s population. As a result, not a great deal is known about what drives the emergence of minority candidates.

When ethnic minority candidates do make it into parliament, they more often represent centre-left parties. This fact is generally recognised. What is less frequently acknowledged is that often centre-right parties nominate just as many ethnic minority candidates as centre-left parties, yet these centre-right nominees are generally less successful at winning elections. This raises an interesting question: in what types of districts do the parties run ethnic minority candidates and why do centre-left minority candidates typically fare better than their centre-right counterparts?

We address these questions in our paper: ‘Explaining the nomination of ethnic minority candidates: how party-level and district-level factors interact’. Where previous academics had focused on party-level factors (such as how minority candidates are more frequently nominated by centre-left parties because of these parties’ multicultural ideology and electoral strategies) or district-level factors (minority candidates emerging in heavily minority electoral districts), we argue that descriptive representation emerges as an interaction of these two forces.

Specifically, we introduce a novel and generalisable model for how ethnic minority candidates get nominated. We argue that ethnic minority population percentage in a district is a key factor, because it makes recruitment easier, and the electoral payoff is greater. However, most ethnic minority voters are centre-left partisans and so will be more responsive to recruitment and to electoral appeals if they come from centre-left parties, who in turn have more of an incentive to pay attention to district demographics.

Our hypothesis, then, is that ethnic minority nominees are most common when two conditions are met: first, the party doing the nominating is a centre-left party, and second, the district where the nominating occurs is a heavily ethnic minority district. We include data from Australia, the UK and the US, to test our hypothesis. We find evidence – particularly from the US and UK – that ethnic minority nominees are indeed most common under these conditions. The British Labour Party, the Democrats in the US and to a lesser extent the Australian Labor Party are more responsive to district minority percentage than their centre-right counterparts (the Conservative Party, Republicans and the Liberal Party/Nationals respectively).

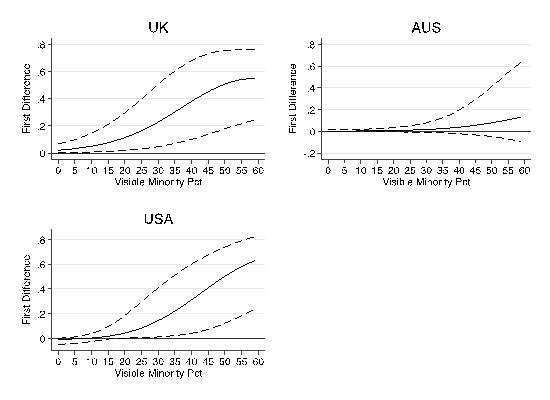

This helps us understand how, cross-nationally, descriptive representation of ethnic minorities occurs. The figure below shows that in the UK and US centre-left parties become more likely to nominate minority candidates (compared to centre-right parties) as the minority population in a district increases. That is, the lines show the increasing difference (the marginal effect) between centre-left and centre-right parties as districts have a greater non-white percentage. At higher levels of this percentage, centre-left parties are much more likely to nominate an ethnic minority candidate, but at lower levels, they are barely more likely. This shows that we need to study party-level and district-level factors together.

These findings also help to illustrate why centre-right parties have a hard time getting minority candidates into office, despite nominating a number of minority candidates. Districts with the greatest proportions of ethnic minority voters are often some of the safest seats for centre-left parties. This implies that when centre-right parties nominate candidates in heavily minority districts, these candidates are likely to lose. Thus, centre-right parties most likely have to nominate minority candidates in less diverse, more safely conservative districts if they wish to have minority candidates actually win. This is a plausible goal because it can improve national coverage and can be part of an effort to ‘politically mainstream’ race.

Figure: difference in the probability of nominating an ethnic minority candidate between centre-left and centre-right parties

Our findings help to shed light on when and where major political parties nominate ethnic minority candidates and where these candidates are likely to win. We show that both the characteristics of the party and the district shape minority representation. The interaction of these two variables is particularly important to understanding the observed pattern of minority candidate nominations.

Perhaps most important, institutional reforms should bear this in mind: increasing the non-white percentage in a district does not linearly increase the probability of descriptive representation. Instead, the effects of demographic changes (or gerrymandering/majority-minority district lines) will be filtered through the spinning kaleidoscope of national party competition.

This article represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit.

It draws on the authors’ paper: ‘Explaining the nomination of ethnic minority candidates: how party-level and district-level factors interact’, published in the Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties.

About the authors

Benjamin Farrer is assistant professor of environmental studies at Knox College.

Benjamin Farrer is assistant professor of environmental studies at Knox College.

Josh Zingher is assistant professor at Old Dominion University in the Department of Political Science and Geography.

Josh Zingher is assistant professor at Old Dominion University in the Department of Political Science and Geography.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] https://www.democraticaudit.com/2018/01/30/increasing-ethnic-minority-representation-why-both-politic… […]