Far right politics in Germany: from fascism to populism?

The rise of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) was one of the major stories of the 2017 German elections. As Tomáš Nociar and Jan Philipp Thomeczek write, there has been a tendency among some commentators to draw parallels between the AfD and extremist or fascist parties from Germany’s past. They argue that this is both unhelpful and inaccurate, and that the AfD has far more in common with other ‘populist’ parties who have had success in recent European elections.

AfD demonstration, 2015. Picture: Stephan Dingas, via (CC BY-NC 2.0)

There is a current, often criticised trend to use the term populism to describe contemporary far right politics. One of the frequent objections usually coming from the political left is that the concept is not negative enough to capture all the malicious aspects of the far right and therefore helps to legitimise it. However, the often-proposed solution, to use the word ‘fascism’ instead, may be even more problematic.

Populism as a phenomenon is a relatively new trait within far right traditionally elitist ideological circles. Several authors point out that it is precisely populism that distinguishes the traditional post-war antidemocratic extreme right, which was inspired by interwar fascist movements, from the modern populist far right parties. According to Piero Ignazi, the main difference between the new forms of far right and the traditional extreme right is that the latter is, among others, also characterised by antidemocratic nostalgia for interwar fascism expressed in references to its myths, symbols, slogans or the ideology of fascism. Does that mean that populism and fascism are mutually exclusive? The situation is not that straightforward, and the relationship between populism and fascism is more nuanced.

One of the most widespread definitions of populism today is by Cas Mudde who sees it as a “thin ideology that considers society to be essentially divided between two antagonistic and homogeneous groups, the pure people and the corrupt elite, and wants politics to reflect the general will of the people”. Only if these three necessary elements (anti-elitism, people centrism and the emphasis on the ‘general will’) are present can we actually speak of populism.

Even though interwar fascist movements were strongly criticising the “established elite” as well as frequently referring to the people, they were never in favour of the idea of the people as sovereign and the general will. In fact, because of their elitist and autocratic legacy embodied in the ‘Führer Principle’, fascist movements always despised the idea of popular sovereignty. In contrast, populists support democracy but pursue, according to Takis Pappas, “democratic illiberalism”: a majoritarian form of democracy that rejects liberal elements such as checks and balances and minority rights. Therefore, we can conclude that, while the classical fascist movements show conceptual overlap with populism, they neither were nor are populists as such.

The situation is slightly different with the contemporary post-war far right. Those parties are aware of the ineffectiveness of the extreme right´s old ideological framework consisting of biological racism, anti-Semitism, and anti-democracy, as Jens Rydgren argues. It is the result of the delegitimisation, stigmatisation and consequent marginalisation of anything that has been associated with Nazism or fascism after WWII. This new type of populist radical right party either never developed or dropped the antidemocratic sentiment in favour of a populist critique of the establishment.

Instead of biological racism, they now articulate ethnonationalist xenophobia and cultural racism based on the concept of ethnopluralism. Here, the emphasis is put on the supposed “incompatibility” of different cultures instead of a hierarchical relationship of “races”. These, on first sight insignificant ideological differences, played an important role in legitimising the originally discredited far right ideology. As a result, the new far right managed to mobilise xenophobic public opinion without being stigmatised as racists. At the same time, through a populist critique of the establishment, they managed to present their criticism of the current liberal democratic system without being marginalised or banned for being extremists.

Perhaps there is no better illustration of this argument than the recent electoral success of the Alternative for Germany (AfD). The fact that they entered the newly elected German Bundestag immediately triggered several headlines comparing today’s situation to the rise of Nazi fascism in 1930. However, is it really the return of fascism that is haunting Germany, or did Germany simply end up as an exception regarding the rise of the populist radical right in Europe?

The case of Germany: Why the AfD succeeds where the NPD failed

The difference between the traditional extreme right and the contemporary populist radical right can best be exemplified when looking at the history and ideology of two far right parties in Germany: the National Democratic Party (NPD), founded in 1964, and the Alternative for Germany (AfD), founded in 2013.

Let us first look at the NPD. The party was founded by former members of the German Reich Party (DRP), a party that promoted a neo-Nazi ideology. As Armin Pfahl-Traughber argues, the NPD has focused heavily on the anti-immigration issue and propagated an ethnically homogenous German Volk while fighting multiculturalism. The NPD also addresses typical populist themes framed in strong anti-systemic language. The party uses terms like “system parties” that have also been used by the National Socialists and strongly criticises a perceived “Überfremdung” (foreign infiltration) by migrants.

The main reason why the NPD never lost their extremist stigmatisation is due to examples of party representatives glorifying the Third Reich. Former party leader Udo Voigt called Hitler “a great German statesman” and proposed Hitler’s deputy Rudolf Hess for the Nobel Peace Prize. The anti-democratic sentiment, which becomes visible through these examples of nostalgia, demarks the conceptual border between populism and extremism. Regarding international cooperation, the NPD allies itself with other extremist parties and is a member of the Alliance for Peace and Freedom along with parties such as Greece’s Golden Dawn or Kotleba – People’s Party Our Slovakia, the only two truly extreme right parties with seats in national parliaments of EU member states. All of these parties are or were investigated by state bodies with a view to banning them.

The story of the Alternative for Germany is a very different one. Originally, the party started in 2013 as a neo-liberal party with a strong focus on Euroscepticism. “Alternative” was originally addressing the return to national currencies. In 2015, Frauke Petry gained control over the party, the leading figure of the national-conservative wing who re-orientated the party towards its current course of nationalist populism. In the following period, the emphasis on national/nationalist discourse (“Germany”, “Germans”, “Volk”) became stronger.

Furthermore, they aim to re-establish terms like “völkisch” that were misused by the Nazis. Even stronger are their articulated anti-establishment feelings that are mainly attacking the old and established parties (“Altparteien/etablierte Parteien”) and public broadcast services, which are accused of manipulating public opinion. They identify a “political class” who are blamed for using their power to minimise the political influence of citizens. Chancellor Merkel is at the centre of their criticism since she is identified as the person responsible for the refugee crisis and is deemed to have thus betrayed “the people”.

The AfD highlights their commitment to procedural democratic principles, but, like other populist parties, has a specific, majoritarian driven form of democracy in mind. That becomes visible, for example, in their demand for referendums and initiatives at the federal level. At the same time, institutions of the current liberal and pluralist democracy should be weakened, according to the party. This includes the disempowerment of public broadcast services and lowering the salary of politicians. Unlike the NPD, the AfD is currently not subject to universal stigmatisation, although single members are under surveillance by the Office for the Protection of the Constitution. In January 2017, the party organised a gathering of the EU parliamentary populist far right group Europe of Nations and Freedom and invited Marine Le Pen and Geert Wilders.

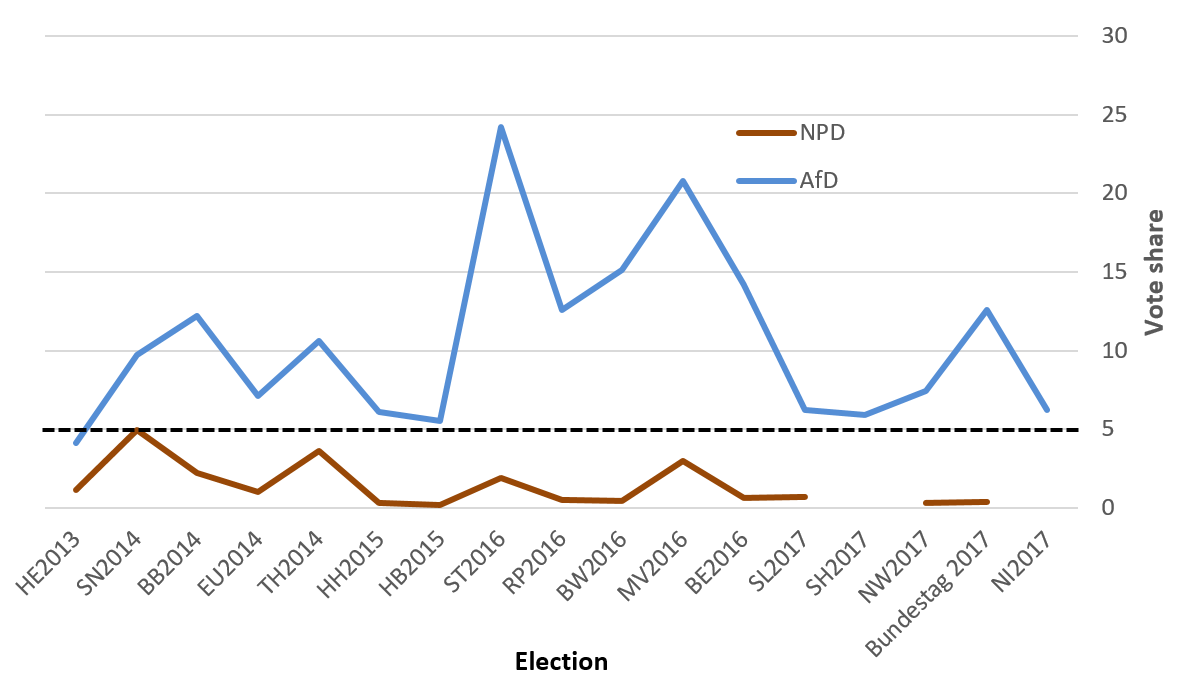

Chart: Vote share for the NPD and AfD in state, national and EU elections since 2013

Note: Each state election is indicated with the abbreviation of the state’s name, with EU2014 referring to the 2014 European Parliament elections and Bundestag 2017 referring to the 2017 federal elections. Figures were compiled by the authors.

The key factors in the AfD’s success have been the mobilisation of voters using xenophobic and populist resentments that have become socially acceptable through the discourse around refugees, and the transferring of anti-Muslim, anti-refugee, and anti-establishment attitudes into votes. The rise of the AfD made the NPD completely insignificant at an electoral level, even in former strongholds. The conclusion here is that despite domestic analysts and commentators being shocked at the AfD’s success, what Germany is currently facing is not the return of fascism, but something that other EU countries have been experiencing for years now. It is the rise of a populist radical right that is successful precisely because of its populism and not because it embodies fascism or extremism.

This article represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit. It was originally published on the LSE European Politics and Policy blog.

About the authors

Tomáš Nociar Tomáš Nociar is a Lecturer at the Department of Political Science at the Comenius University in Bratislava where he works on his PhD. His research interest includes far right ideology, extremism and populism in Central Europe.

Tomáš Nociar Tomáš Nociar is a Lecturer at the Department of Political Science at the Comenius University in Bratislava where he works on his PhD. His research interest includes far right ideology, extremism and populism in Central Europe.

Jan Philipp Thomeczek Jan Philipp Thomeczek is a PhD student at the University of Duisburg-Essen. In his dissertation, he is analysing populism in Germany. He is a project manager at Kieskompas where he is responsible for Voting Advice Applications in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland.

Jan Philipp Thomeczek Jan Philipp Thomeczek is a PhD student at the University of Duisburg-Essen. In his dissertation, he is analysing populism in Germany. He is a project manager at Kieskompas where he is responsible for Voting Advice Applications in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.