Why the media helps make Hungarian elections so predictable

Hungary will hold parliamentary elections on 8 April, with polls suggesting Fidesz, led by incumbent Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, is in a strong position to hold on to power. Andrea Fumarola argues that a sharp decline in press freedom over the last decade has helped Orbán to consolidate his political position, but that the dominance of Fidesz has come at some cost to the quality of Hungarian democracy.

Viktor Orbán. Picture: European People’s Party, via (CC BY 2.0)

On 8 April, Hungarian voters will go to the polls to elect the 199 members of the country’s national parliament (Országgyülés). According to opinion polls, Viktor Orbán’s incumbent party, Fidesz, is projected to win a landslide majority with about 53% of votes and secure an even higher number of seats than the 133 seats Fidesz currently shares with its minority coalition partner the KDPN. This is partly thanks to the strong disproportional effect of the voting system.

Orbán’s route to re-election appears to be secure, which has shifted the focus of commentators toward the race for second place between the far-right Jobbik and the Socialists (MSZP). But this outcome is also the product of a general lack of integrity within the electoral process that involves, among other features, the degree of freedom afforded to the Hungarian media.

A ‘point of no return’? The 2012 electoral reform

The last parliament was elected in 2014 with a reformed electoral law that had been promoted by Orbán’s government two years earlier. The new law substantially reduced the total number of seats (from 386 to 199), abolished the two-round system that had previously been used, and redesigned the country’s electoral boundaries. These provisions, included in a broader reform of the Constitution, were harshly criticised by commentators and civil society representatives.

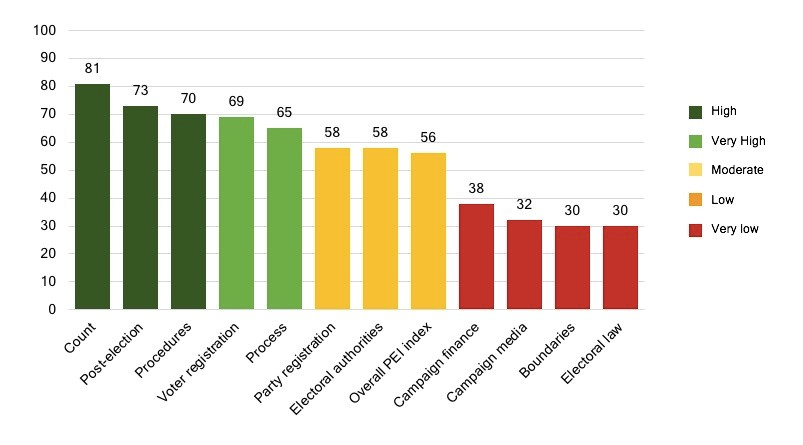

Several NGOs and researchers have highlighted some of these concerns. The Electoral Integrity Project, for instance, which calculates a ‘Perception of Electoral Integrity (PEI)’ index based on expert assessments, assigns Hungary one of the lowest scores among EU member states: 56/100, which is 27th out of the 28 EU members. However, as Figure 1 shows, some of the individual components of this overall score were even more problematic, notably in terms of Hungary’s electoral law, electoral boundaries, campaign finance and the role of the media in campaigns.

Figure 1: Performance of Hungary on individual components of the ‘Perception of Electoral Integrity’ index (2017)

Source: Elaboration from PEI 5.5; Norris, Wynter, Gromping (2017)

While the limits of the electoral law and its effects on constituency boundaries have been discussed previously, the state of the media merits attention given the impact a substantial lack of independence can have on electoral outcomes. The PEI sub-dimension for campaign media captures how fairly Hungarian news media covered the 2014 parliamentary election. The low score assigned here raises serious questions over the functioning of the electoral process. Media organisations not only inform citizens about the performance of the government, but also serve as a public arena for all parties to make their case to the electorate.

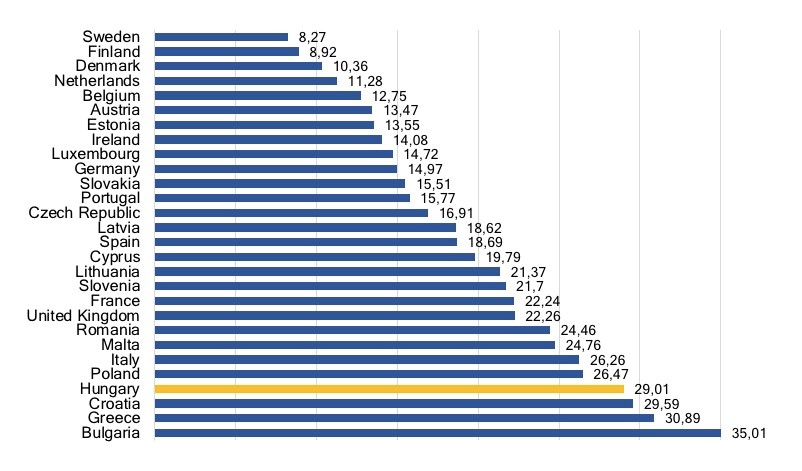

Figure 2 shows the 2017 World Press Freedom Index calculated by Reporters Without Borders. The index is based on an expert survey and captures seven components of a country’s performance in terms of pluralism, media independence and respect for the safety and freedom of journalists. The index ranges from 0 to 100, with 0 being the best possible score and 100 the worst.

Figure 2: How EU countries compare in the 2017 World Press Freedom Index

Note: WPF 100-point index by country (2017). Source: Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

As can be seen in the figure, Hungary ranks near the bottom of the 28 EU member states, also registering the worst performance in the Visegrád group. This is particularly relevant considering that, together with Poland and Czechoslovakia, Hungary was at the forefront of the revolutionary wave that spread across Central Europe in 1989 and for a long time served as a model for the rest of the region due to its relatively high standards of living and the implementation of democratic and liberal principles. There is concern now that this process is stalling as the current government seeks to tighten its grip over the media.

Orbán’s grip on the Hungarian media

As one of the leaders of the democratic transition, Hungary was known for having a rather free and plural system of information. This was partly thanks to the 1989 Constitution, which sought to establish and protect press freedom and ensure a variety of news outlets could freely operate. Although political parties and interest groups attempted – perhaps unsurprisingly – to influence the media during the first two decades of democracy, media organisations were mostly privately owned while the 1996 media law guaranteed shared appointments between the government and opposition parties on the boards overseeing state television and radio.

This rather positive trend continued until 2011-12, when Fidesz started to tighten the government’s control over the media through a revision of the Constitution and a systematic modification of media legislation. The impact of these measures has been captured by organisations such as Freedom House. The measures have included tighter provisions to centralise control over independent media and journalists, notably through the creation of a National Media and Infocommunications Authority (NMHH), whose board has strong links to the governing party. They have also included cutting funds to put independent private outlets under pressure, while pro-government media organisations controlled by Hungarian companies have allegedly received more favourable treatment.

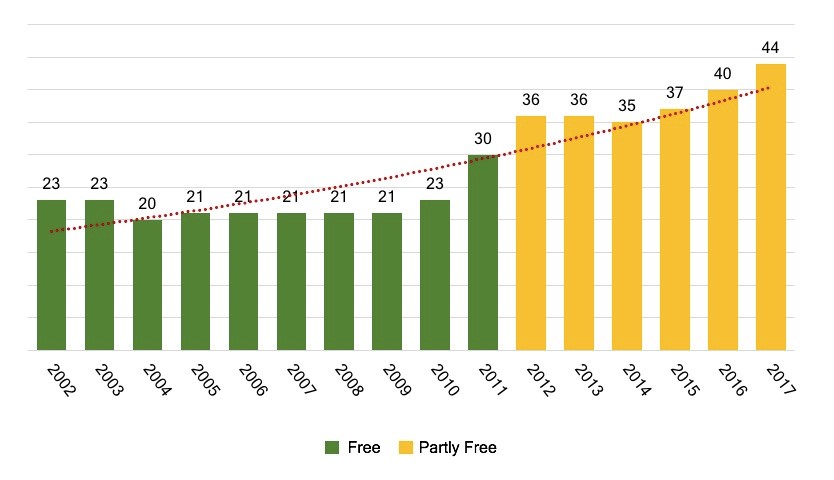

This was the case of Népzabadság – the most important Hungarian daily – which suspended its online and print editions after it was acquired by new ownership. Opposition parties have claimed that the closure of the paper reflected links between the new ownership and the government. The same paper ran a front page in 2011, shortly after Orbán came to power, claiming that “Freedom of the press in Hungary has come to an end”, which was written in 23 official languages of the European Union. Figure 3 illustrates how Hungary has fared since 2002 in the annual Freedom of the Press reports produced by Freedom House, where a higher score indicates a lower level of press freedom.

Figure 3: Freedom of the Press score for Hungary (2002-2017)

Note: FoP 100-point index (2002-2017). Source: Freedom of the Press, Freedom House (2017)

The decline in press freedom shown above stems from several sources. Alongside the effect of new legislation, advertising revenues in the private sector have also been progressively reduced due to the actions of the national tax authority, with favourable conditions being created for a concentration of media ownership. And the subsequent lack of pluralism and freedom has had a negative impact on the quality of political discourse. There has been a gradual process of ‘tabloidisation’, with a reduction in the quality of international and political news coverage. Pro-government coverage of news items, as shown during the 2016 referendum campaign, could also have significant consequences for the 2018 election given the government’s ability to effectively set the agenda and influence public opinion.

International observers, especially through the UN and OSCE, have repeatedly expressed concern about the state of the Hungarian media system and the decline in independence and pluralism that has been witnessed over the last decade. The issue goes to the heart of safeguarding democracy in the country. The last election in 2014 highlighted several problems, but the situation four years later has not improved and, on the contrary, shows signs of a further deterioration which will have an impact on the election campaign.

The existence of a free press is a fundamental check against the misuse of political power. Research has shown that better informed citizens are also more civically engaged and are better equipped to ensure government responsibility. This is key to electoral accountability and if press freedom declines, so too will the quality of Hungarian democracy.

The article gives the views of the author and not Democratic Audit. It was originally published on the LSE European Politics and Policy blog.

About the author

Andrea Fumarola is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Comparative Politics at the University of Bergen. In 2016 he was Visiting Fellow at the University of Sydney within the Electoral Integrity Project and Visiting Researcher at the GESIS Eurolab in Cologne. He tweets @_F_Andre_

Andrea Fumarola is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Comparative Politics at the University of Bergen. In 2016 he was Visiting Fellow at the University of Sydney within the Electoral Integrity Project and Visiting Researcher at the GESIS Eurolab in Cologne. He tweets @_F_Andre_

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.