Book Review | Orbán: Europe’s New Strongman by Paul Lendvai

In Orbán: Europe’s New Strongman, Paul Lendvai examines how, via a ‘lightning-speed assault’ on its democratic features, Hungary can now be better characterised as an authoritarian system under the rule of Viktor Orbán. Exploring such topics as the deterioration of the country’s rule of law, the end of the separation of powers and mass clientelism, Lendvai succeeds in tracing Hungary’s rapid slide towards authoritarianism in this excellent book, writes Paul Caruana-Galizia.

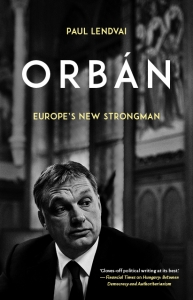

Victor Orbán, 2011. Picture: European People’s Party, via (CC BY 2.0)

Orbán: Europe’s New Strongman. Paul Lendvai. Hurst Publishers. 2017.

From fascism to Stalinism to communism, it looked like Hungary had finally broken free of authoritarian rule in 1989. Just under ten years later, Viktor Orbán won the country’s third free election in 1998, providing him with his first taste of power as Prime Minister. Having won by a whisker, he was dropped after one term, but what looked like a brief swerve back onto the authoritarian path was, when seen through the rearview mirror, a clear direction of travel. Orbán was returned to power in 2010 with two-thirds of the seats in Hungary’s parliament: ‘we only have to win once, but then properly,’ he had said from opposition (94). This time, he won the power to rewrite Hungary’s constitution, and he meant it when he said that ‘the new state that we are building in Hungary is an illiberal state, not a liberal state’.

Other descriptions of Orbán’s new state have been less kind. Paul Lendvai summarises them in his new book, Orbán: Europe’s New Strongman, in a chapter called ‘The New Conquest’ (Chapter Ten). Journalist Rudolf Ungváry calls it a ‘fascistoid mutation’ (92); former education minister, Bálint Magyar, ‘a post-communist mafia state’ (91). There are others, but the one that Lendvai favours is more subtle, from another former education minister, András Bozóki: Hungary is now ‘a hybrid regime’ in which ‘the features of an authoritarian system are stronger than those of a democracy’ (92).

Lendvai covers these authoritarian features over the course of his excellent book – deterioration in Hungary’s rule of law; the end of the separation of powers; gerrymandering; the creation of an oligarchy; grand corruption; and mass clientelism. It’s a testament to Lendvai’s writing that he can sketch the evolution of an authoritarian state over 230 pages. Perhaps this is because Orbán’s changes were so fast – a ‘lightning-speed assault’ (94) – and because there are so few democratic features left on which to write. Indeed, for Lendvai, Hungary’s only remaining democratic component is ‘the theoretical possibility of removing the government’ in an election (92).

What to make of Orbán himself? He calls himself a ‘right-wing plebeian’. In his book’s subtitle, Lendvai describes him as ‘Europe’s new strongman’. Lendvai, an 88-year-old Hungarian-born journalist who has written widely on Central Europe and authoritarianism, knows that Orbán is ‘new’ only in the sense that he is the latest issue in a long series of European strongmen. He knows there is little that is novel about Orbán’s governing techniques and route to power, two themes he expresses lucidly in his book.

There’s a long debate on whether strongmen shape history or whether history proceeds regardless. Lendvai’s view of Orbán is that he is more shaper than shaped. He starts with a chapter, ‘The Personal Touch’, describing Orbán’s initial rise as liberal student activist. The scene: Heroes’ Square, Budapest, 1989, when communist Hungary was collapsing and anything must have seemed possible. A 26-year-old Orbán rises to speak:

If we trust our own strength, then we will be able to put an end to the communist dictatorship. If we are determined enough, then we can compel the ruling party to face free elections […] If we are courageous enough, then, but only then, we can fulfill the will of our revolution (8).

József Debreczeni, author of a previous Orbán biography on which Lendvai relies heavily, described this moment as ‘the meeting of extraordinary luck with extraordinary talent’ (8).

Above all, strongmen are both forceful orators and highly cynical. Something else Orbán declared in his liberal student activist days: ‘the leadership of governing parties […] are very much inclined to reject criticism of government policy by suggesting the opposition or media are undermining the standing of Hungary, are attacking the Hungarian nation itself’ (26). There are two reasons why this may sound familiar. First, it outlines how strongmen everywhere rebut criticism. They associate themselves with the state and nation, so that criticism of them is criticism of these too. Their critics become ‘traitors’ (if domestic) or, in that well-known Stalinist phrase, ‘enemies of the people’ (if domestic or foreign). Second, we see some of Orbán’s u-turn cynicism in the way he now deals with his critics as Prime Minister. Under fire for his attack on Hungary’s rule of law, Orbán says his critics are attacking Hungary. Lendvai observes that this ‘nationalist-populist’ behaviour both mobilises Hungarians and separates ‘the cause of the nation’ from ‘that of liberty’ (113).

Personal traits are necessary, but insufficient. Lendvai shows us how Orbán’s route to power opened up when his main opposition, the Hungarian left, disappointed the electorate with a long-running mixture of economic incompetence and corruption. Orbán cast himself as the new, youngish outsider against a left characterised as ‘a disgusting snake pit of old communists and leftwing careerists posing as social democrats’ (74). Strongmen feed off a sense of exclusion among voters. Many Hungarians lost out in the switch from communism to free-market capitalism. What do you sell to individuals who feel excluded? You sell them greatness – fantasies of national greatness. Orbán looks back with regret at the immense territories his people’s country lost after World War I. He plays on a sense of national loss better than any Hungarian politician.

Power. Once strongmen seize it, they grow it. They occupy the state, repress civil society and the media and engage in clientelism: Jan-Werner Müller’s three techniques of populist government, alluded to by Lendvai (106). In particular, Orbán is bent on the ‘political annihilation of his opponents and rivals’ (38). Lendvai frames this in terms of Orbán’s combative personality, but it has practical ends too. Backed by his supermajority, Orbán’s new constitution, the ‘Fundamental Law of Hungary’, gave him control of the constitutional court and ended the separation of powers in Hungary. It was ‘an unconstitutional coup […under] the cover of constitutionality, with constitutional means’ (110). The academic János Kornai describes Orbán’s aims since 2010 as ‘the systematic demolition of the fundamental institutions of democracy’ (92). Thus, Orbán can now mean it when he says his critics are ‘enemies of the state’ (231).

For all their posturing, strongmen’s attacks on civil society betray what Francis Fukayama calls an ‘authoritarian thin skin’. In June 2017 the Hungarian parliament passed a law on the ‘Transparency of Organisations Supported from Abroad’. Much like Vladimir Putin’s draconian ‘foreign agents’ law’, the Hungarian law requires NGOs with foreign funding to be placed on a register, publicly declare they receive foreign funding and identify individual foreign donors (211). Failure to comply means financial sanctions or expulsion. Amnesty International called it ‘an assault on civil society [that] is aimed at silencing critical voices within the country’. It is against this backdrop that George Soros, who founded the Central European University (CEU) in Budapest and funds anti-corruption and pro-democracy programmes, became Orbán’s ‘public enemy number one’ (208). Orbán is threatening to shut down CEU while continuously and aggressively vilifying Soros, accusing him of weakening the nation state. As Lendvai writes, this is not so much a personal conflict; rather, Soros represents liberal democracy.

When it comes to the media, strongmen seek to either outright silence or slyly co-opt critical voices. Fidesz, Orbán’s party, began building a media empire long before his election through a group of friendly oligarchs (75-76). Once in power, Orbán used his supermajority to pass a media law that empowered him to take over public broadcasters, appoint apparaticks to their management, distribute subsidies to friendly non-state media and run a Media Council that allocated frequencies, imposed sanctions and dictates the meaning of ‘balanced news’ reporting (115). Orbán’s end goal? The ‘disappearance of objective truth’ (207). The OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media described the law as ‘totalitarian’ (115).

Strongmen use their control of the state not just to repress critics, but also to patronise clients. Under Orbán, clientelism is practised openly and with public moral justification. Orbán claims that his people are the real people and so deserve the support of their state. Here’s András Lánczi, Orbán’s main ‘public intellectual’ tool: ‘What is called corruption is actually Fidesz’s supreme policy […] the government has set for itself goals such as the establishment of a group of domestic entrepreneurs, the building of the pillars of a strong Hungary’ (151). Those ‘entrepreneurs’ have with strong state support become Hungary’s oligarchy, building a strong Fidesz rather than a strong Hungary, in the same way Putin created and uses Russia’s oligarchy to support his own mafia state.

Can Orbán be stopped? Lendvai isn’t optimistic. He concludes his book by describing Hungary’s future as ‘bleak’ with little chance for ‘progressive and liberal change’ (230). Yet, it’s unfair to demand solutions of Lendvai: that challenge is hard and beyond the scope of Orbán. Rather, the book is an example of political writing that not only shows us what’s wrong with Hungary and Orbán, but how easy it is for a country to slide towards authoritarianism under a strongman.

Dr Paul Caruana-Galizia is a Visiting Fellow in the Department of Economic History at the London School of Economics. He is the author of The Economy of Modern Malta and Mediterranean Labor Markets in the First Age of Globalization. He tweets @pcaruanagalizia. Read more by Paul Caruana-Galizia.

Find this book:

Find this book:

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.