Italy’s election wasn’t just a populist takeover – it was also about the demise of the left

The Five Star Movement and Lega have been viewed as the key winners from the Italian general election on 4 March, but as Davide Vittori writes, the election was also about the decline of the Italian left. Matteo Renzi’s Democratic Party, which until recently had avoided the fate of other centre-left European parties, suffered a major drop in support, while the radical left has not made the same kinds of gains that have been seen in other southern European countries.

Matteo Renzi. Picture: Palazzo Chigi, via (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

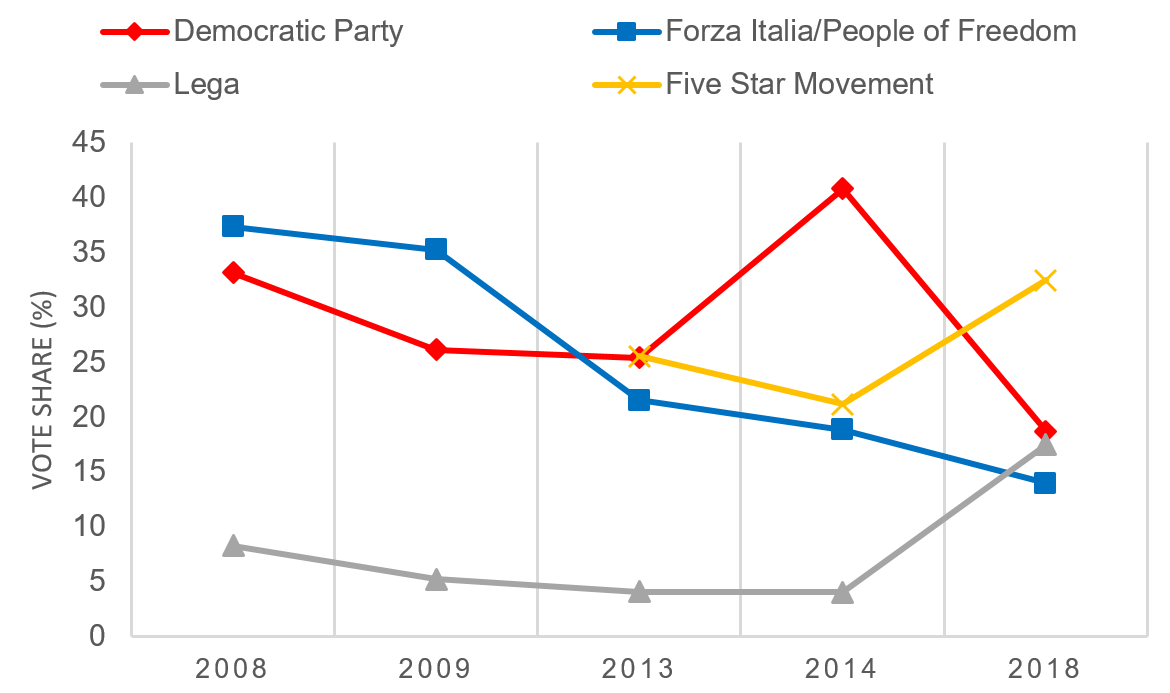

The Italian political landscape has radically changed. At first sight, the results of the two main anti-establishment parties, the Five Star Movement (32.2%) and Lega (17.7%), suggest a populist takeover. Compared to the results obtained by the two parties in previous elections, shown in the chart below, both parties can claim victory. The Five Star Movement was the party with the single biggest share of support in the 2018 election, while Lega now leads the centre-right coalition (which received 37.3% of the vote overall), surpassing Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia.

Chart: Results in Italian general elections and elections to the European Parliament (2008 – 2018)

Note: Compiled by the author. The chart shows vote shares in Italian general elections (2008, 2013 and 2018) alongside vote shares in European Parliament elections (2009 and 2014).

The Five Star Movement was expected to gain the largest level of support of any single party, however, the distance to the second-placed Democratic Party (on 18.9%) was substantial. Nevertheless, neither the Five Star Movement nor the centre-right coalition will have an absolute majority in the Chamber of Deputies or the Senate. The following weeks, and potentially months, will be crucial for determining the nature of the next government, and whether the Five Star Movement’s Luigi Di Maio and Lega’s Matteo Salvini will reach an agreement.

During the campaign, neither party advocated forming such an alliance. This is nothing new for the Five Star Movement, which has always adopted a stand-alone approach to elections: indeed, to illustrate their refusal to enter any post-election alliance, they published a list of potential ministers in advance, whose appointment was non-negotiable in the case of the party failing to win an absolute majority. Lega, on the other hand, primarily emphasised its unwillingness to join a grand coalition with the other centre-left and centre-right parties should there be a hung parliament, which in the end the polls correctly predicted.

The possibility of a grand coalition has disappeared with the fall in support for the Democratic Party. There is now a sharp divide between the ‘old’ party system, embodied by the Democratic Party and Forza Italia, and the ‘new’ parties, but this new polarisation is somewhat paradoxical. Lega is actually the oldest party in the parliament, while Berlusconi has typically defined himself as the ‘non-politician’ of the Italian party system. Matteo Renzi’s initial success as the leader of the Democratic Party was also founded on his image as an outsider from the old party bureaucracy. All four major parties have therefore claimed to exist outside of the mainstream in their own way, but only those who have remained in opposition since the last general election have succeeded (Forza Italia has spent the last few years in opposition, but participated in the government at the beginning of the legislature).

But beyond this new demarcation, the demise of the centre-left was the key story of the election. The result was arguably the worst performance by the left in Italy since the end of the Second World War. The Democratic Party, which suffered a split in its ranks a few months before the election, followed the pattern of many European social democratic parties by enduring declining support. Free and Equal (the party which split from the Democratic Party) also performed far below expectations, securing only 3.4% of the vote, just above the 3% electoral threshold. The poor performance of the left in its traditional strongholds – the so called ‘Red Belt’ that includes areas such as Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria and the Marches – was stunning. In several single-member districts in Emilia-Romagna, where the left had governed uninterrupted since 1970, the Democratic Party fell behind the centre-right coalition and the Five Star Movement.

Following other countries in Europe, the decline of the centre-left has now reached Italy, despite Renzi’s Democratic Party appearing to be an exception to this trend until recently. What was also significant, however, was the poor performance by the radical left, which has experienced its own decline that can be traced as far back as its participation in the centre-left government formed in 2006. While in other southern European countries, as well as France, radical left parties have mounted a challenge to social democracy in recent years, at least some of this support appears to have gone to the Five Star Movement in Italy.

This is not to say that the Five Star Movement should be viewed as a left-wing counterpart to Lega. It currently combines some left-wing proposals – such as a means-tested version of the basic income, environmental protection, and support for public healthcare – with an anti-immigration stance and a relatively unclear advocation of tax-reduction. Indeed, it is perhaps this ambiguity that has allowed the Five Star Movement to become the real catch-all party in Italy.

This article represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It was first published by LSE’s EUROPP – European Politics and Policy blog.

About the author

Davide Vittori is a PhD Student at LUISS University. His main research interests are party politics, movement parties, party organisation and populism. His last publication is Podemos and the Five Stars Movement: Divergent trajectories in a similar crisis (Constellations).

Davide Vittori is a PhD Student at LUISS University. His main research interests are party politics, movement parties, party organisation and populism. His last publication is Podemos and the Five Stars Movement: Divergent trajectories in a similar crisis (Constellations).

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.