Book Review | Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race by Reni Eddo-Lodge

When was the last time you heard a person of colour challenge structural racism – the role of government policies, organisational practices and popular representations in reinforcing racial inequalities – and, in so doing, be widely supported, listened to and heeded? Racial inequalities are stark, yet normalised. White people are privileged yet complacent, and refuse to listen. In her phenomenally brilliant new book, Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race, Reni Eddo-Lodge catalyses an urgent conversation about race in Britain, writes Alice Evans.

Picture: Johnny Silvercloud, via (CC BY SA 2.0)

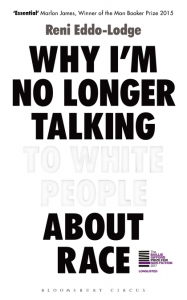

Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race. Reni Eddo-Lodge. Bloomsbury. 2017.

This is the most important book I’ve read in several years. It’s beautifully written, powerful, moving and rightly distressing. As such, this review will be a little unusual. I will not critique the book (as I have others for the LSE Review of Books). This is partly because I am entirely convinced, and partly because that would be fundamentally missing the point. We (white people) stand accused of wilful ignorance; of refusing to recognise structural racism; and of indignantly shouting down proposed reforms. We urgently need to start listening to people of colour, reflecting on our practices and doing far better.

This is the most important book I’ve read in several years. It’s beautifully written, powerful, moving and rightly distressing. As such, this review will be a little unusual. I will not critique the book (as I have others for the LSE Review of Books). This is partly because I am entirely convinced, and partly because that would be fundamentally missing the point. We (white people) stand accused of wilful ignorance; of refusing to recognise structural racism; and of indignantly shouting down proposed reforms. We urgently need to start listening to people of colour, reflecting on our practices and doing far better.

To build empathy and understanding, Reni Eddo-Lodge traces our British history of slavery, lynchings, police brutality and the enduring obstacles that reproduce inequalities in education and employment. To my shame, much of this information was new to me. I did not know that after the First World War (typically memorialised as unity against a shared foe), there were racist lynch mobs in Liverpool and Cardiff. Further, rather than protect the victims, our government repatriated 600 black people, notwithstanding their contributions to the war effort.

Hatred, hostility and police brutality continued in the twentieth century, as Eddo-Lodge eloquently narrates. Yet politicians, films and news media have typically portrayed black (not white) people as violent threats. And that was the myth I grew up with as a child. Kept in a white, established middle-class enclosure, seldom seeing black men in positions of authority or expertise, I distinctly remember fearing them. Eddo-Lodge sees this, perfectly.

Thankfully, I went to an international school, where I interacted with people of colour, recognised our commonalities and stopped making these ignorant, racist assumptions. But like many other characters depicted in Eddo-Lodge’s book, I remained shamefully blinkered to my white privilege. I arrogantly assumed that I was succeeding in school, gaining internships and other wonderful opportunities through hard work and merit alone. I was blinkered to the truth: the obstacles, the hurdles, at each and every single stage, that thwart black lives in Britain. Even if black workers endure and excel, overcoming a system rigged against them, the pay gap widens with A-level qualifications.

And let’s be honest, this isn’t news. As Eddo-Lodge details, we see structural racism every day: most kids who live above the fourth floor of tower blocks are black or Asian. Meanwhile, white people are over-represented in academia, senior management, politics and films. As a philosophy undergraduate, I only read books and papers by white men. I never questioned this.

To build a fairer Britain, we urgently need to start talking about race. Yet, Eddo-Lodge highlights that when people of colour do speak out – pushing for decolonised curricula, affirmative action, short-lists, black film stars – they’re shouted down and vilified. Any attempts to diversify (Idris Elba as James Bond, a black Hermione Granger) are roundly condemned. Cue indignant outrage that Britishness might not always be represented as white. To protect and preserve themselves from these unrelenting attacks, some people of colour want ‘safe spaces’. This is a mistake, explain paternalistic white people. They proceed to tell others who endure profound racism to ‘toughen up and grow a thicker skin’. Indeed, their closed-mindedness seems rather racist … As Eddo-Lodge remarks, we are more outraged by accusations of racism than racism itself.

White solidarity was publicly asserted last week, when Dr. Priyamvada Gopal and others questioned Professor Mary Beard’s remarks about Haiti. Rather than listen and learn from alternative perspectives, many white people defended their hero, and tarred interlocutors with the ‘angry black woman’ stereotype in a bid to delegitimise their critique.

Now, you may be thinking: ‘Sure, those white people are awful. But I’m different. Far from decrying diversity, I welcome it. My favourite film this year is Black Panther!’ Fine, good for you. But does your solidarity go beyond individual consumerism? For instance, when you saw the Telegraph’s nasty smear campaign against Lola Olufemi, did you write to complain, mobilise to protest or just sigh and turn the page?

White British people have greatly benefitted from structural inequalities. Pervasive racism means that we are favoured – in education, employment and politics. And we allow this to persist. As Eddo-Lodge surmises:

White privilege is dull, grinding complacency. It is par for the course in a world in which drastic race inequality is responded to with a shoulder shrug, considered just the norm […] Everyone is complicit, but no one wants to take on responsibility.

Guilty, as charged.

Going forwards, Eddo-Lodge calls for us to listen intently, learn from marginalised perspectives, intervene as bystanders and collectively address profound inequalities. She emphasises that, collectively, we have the power to create the world we want to live in. Racial equality is not a spectator sport. Although inequalities are systemic, change starts with us.

Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race should be compulsory reading in all schools. It is the building blocks of a fairer Britain.

This review gives the views of the author, and not that of Democratic Audit. It was originally published on the LSE Review of Books blog.

This review is published as part of a March 2018 endeavour, ‘A Month of Our Own: Amplifying Women’s Voices on LSE Review of Books’. If you would like to contribute to the project in this month or beyond, please contact them at Lsereviewofbooks@lse.ac.uk.

Alice Evans is a Lecturer in the Social Science of Development at King’s College London. She researches inequality, social change and global production networks. Read more by Alice Evans.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.