England’s local elections: how councillor numbers are being reduced by stealth

Local elections are being held across England on 3 May, but finding out where and for which seats is not always straightforward. Of more concern, writes Chris Game, is that the number of local councillors is gradually being reduced, in a process that lacks transparency, proper scrutiny and a clear, democratic rationale.

Local election count. Picture: Coventry City Council, via a (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

Local election count. Picture: Coventry City Council, via a (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) licence

If, as I did, you worked in the pre-internet age for something called the Institute of Local Government Studies (INLOGOV), writing on matters electoral, the weeks preceding the annual local elections could be trying. Even in the Citizenship Test era, it is hardly a deportable sin for an English elector to be uncertain if their council is elected in its entirety every four years, by thirds in three years out of four, or even in alternate years by halves – and, in the latter cases, whether this year’s elections involve their particular ward.

Such complicated arrangements incline me strongly to support adopting the practice of some countries, long backed by the Electoral Commission, the 2007 Councillors Commission and others, of a single four-yearly national or at least regional Local Elections Day for all councils – though not, as in Sweden, on the same day as parliamentary elections with different coloured ballot papers, and probably not in mid-November, like Denmark’s.

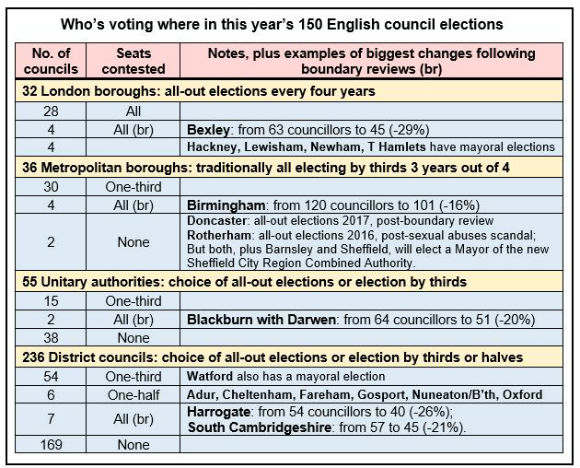

This is not, however, one of the points of this blog, the lesser of which is a tabular demonstration indicating who should and shouldn’t be voting next Thursday, for which seats and where.

The table is intended to be accurate, comprehensive in its way, and illustrative of the heffalump traps facing reporters and broadcasters come election night on 3 May. But nowadays much fuller lists are easily available, including details regarding the councils’ current political compositions and control, from, inter alia Democratic Dashboard (which is searchable by postcode), Wiki and Open Council Data UK. The latter is particularly comprehensive, and any errors usually minor and inconsequential – though not entirely in this exceptional instance. For – when I checked, anyway – it omits Blackburn with Darwen as one of the two unitary councils, together with Hull, holding all-out elections this year to implement the proposals of a comprehensive boundary review, a process that constitutes the principal reason for producing my own modest table.

By my reckoning, of the 4,262 councillors elected at this round of local elections four years ago, the seats won by 99, or well over 2% of them, have already been lost before a single vote has been cast – lost not just to them, but to their councils, and almost certainly permanently. The 99 are the net sum of the rulings of the Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) following its reviews of the 17 councils that will be implementing those rulings in all-out elections this May – although ‘net’ is somewhat misleading, as it represents eight proposals to reduce the number of council seats and no proposals for increases.

Next year, a further net 51 council seats are already set to go, and last year it was 34. So, in three years that’s equivalent to the abolition of about five councils’ worth of democratic representation – and that’s from a start in England of a 2,250:1 citizens-to-councillor ratio, which is already several times higher than almost any other EU country. At which point, I should probably declare a personal (citizen and academic) interest, since my own council of Birmingham – as noted in Jack Bridgewater’s recent election preview – has contributed 19 of this year’s lost 99, despite the fact that three significantly smaller big cities also reviewed in this cycle – Leeds (99), Manchester (96) and Newcastle (78) – were allowed to retain all of theirs.

It’s tempting to misquote here the Lutheran hymn about God moving in mysterious ways, his wonders to perform. The LGBCE obviously isn’t that mysterious, for it publishes all its recommendations, proposals and reports and a certain amount of its reasoning. Only rarely, though, are these considered collectively. The Commission’s aims, too, are distinctly more modest than God’s, being limited to achieving its singular interpretation of electoral equality: namely, equalising the number of electors represented by each councillor in any particular local authority. About that intra-council form of electoral equality it is passionate, and it’s what prompts most – but importantly not all – of its reviews.

However, about inter-council electoral equality, and also about other aspects of intra-council equality, it is passionately indifferent. Birmingham was a special case, as it was referred to the LGBCE as a result of Lord Kerslake’s review of the city council’s governance and organisation. Kerslake was unimpressed, identified the number of councillors as one of the council’s weaknesses, and recommended cutting them to 100 and presumably increasing their workload – a recommendation that the LGBCE endorsed and implemented almost precisely, though far from unproblematically. Its draft ward proposals generated an emotional spasm that canvassers in these local elections would almost pay for, and produced ‘over 2,000 submissions’, aka protests, to which, as is their wont, the Commissioners sought to respond. Edgbaston Cricket Ground was returned to an Edgbaston ward, the historic Jewellery Quarter disentangled from Winson Green prison, Moseley village moved back from Balsall Heath to a two-member Moseley ward, and much more besides.

Council size, however, was non-negotiable. The Commission regards the current 120 councillors as representing an average of just over 6,000 electors each, although, since all are elected to three-member wards and have to canvass, deal with and represent all ward residents, the more meaningful figures would be 18,000 electors and 30,000 persons, which is considerably higher than any other single-tier authority.

In future, 37 of the 101 councillors will represent single-member wards, with 64 in two-member wards. For these upcoming elections, therefore, candidates in the former group will presumably be almost relishing campaigning for the first time for the votes of ‘only’ some 7,000 or so electors – especially as they see their colleagues canvassing similarly new electorates, but twice the size. For in our system, electoral equality is for generally unaware electors, not acutely aware aspiring councillors.

This all highlights the main purpose of this blog: to demonstrate how this most under-appreciated tier of our political class is being gradually but steadily whittled away in a kind of policy vacuum. There is nothing in the LGBCE’s terms of reference requiring a reduction in the number of councillors. However, rather than equalising upwards in response to generally growing populations, it almost always equalises downwards.

There are also several instances – including Bexley LBC, Chichester and East Cambridgeshire DCs – in which reviews were initiated not by the Commission, but by the council itself wishing to reduce its own elected membership, whether for financial or other reasons usually not being stated. In both types of reviews, though, the Commissioners’ phraseology, though varying slightly, is that they are satisfied that ‘decreasing the number of members by XX will make sure the council can carry out its roles and responsibilities effectively’.

Most council officers will have had the occasional thought that ‘if it weren’t for those pesky members…’, but it’s a little concerning, especially at election time, to realise that there’s an unelected body already doing something about it.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

About the author

Chris Game is an Honorary Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Local Government Studies (INLOGOV) at the University of Birmingham.

Chris Game is an Honorary Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Local Government Studies (INLOGOV) at the University of Birmingham.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.